The day before the 50th anniversary March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a handful of the tens of thousands who showed up at the Lincoln Memorial converged on a less noble setting.

The headquarters of the American Legislative Exchange Council, the right-wing advocacy group commonly known as ALEC, are housed in a ten-story, colorless box. In 2013, the group moved its main operations to 2900 Crystal Drive, Crystal City, a section of Arlington, Virginia, that looks like a suburban office park transplanted onto an urban grid. There’s nothing on the facade marking the presence of ALEC headquarters – only “2900.” At lunchtime, no one walks in or out. It’s what you’d expect a legislative factory to look like.

Truthout combats corporatization by bringing you trustworthy news. Click here to join the effort.

Amid on-and-off showers, ALEC’s walls echoed, “We got next!” Youth activists from Florida, New York, California and across the Midwest came to condemn ALEC’s warehouse of model bills, which feed pro-corporate, anti-worker and racially charged ideologies. In protest of Stand Your Ground, the law that allowed George Zimmerman to go free after killing 17-year old Trayvon Martin, bodies lay spattered with blood in an ACT UP–esque “die-in” outside. Security refused to open up; unable to hand-deliver a letter to the group, signed “We know who you are and will fight you until we win,” activists taped it to the front door.

Through its role in spreading laws like Stand Your Ground, ALEC perpetuates the “kind of society we live in that says that we look scary, that we look ugly, that we’re nothing,” said Ciara Taylor, a member of Florida’s Dream Defenders. A week earlier, the group left the Capitol in Tallahassee after a monthlong occupation demanding a special legislative session to repeal Stand Your Ground, outlaw racial profiling, and clamp down on school-to-prison policies.

A coffin sits at the entrance to ALEC headquarters. (Photo: James Cersonsky)“We’re trying to build a movement where black bodies are loved,” said Kelsei Wharton from the Black Youth Project 100, a national group that had its inaugural meeting the weekend of Zimmerman’s acquittal. “We need to vex the quo. We need to get rid of ALEC completely.”

A coffin sits at the entrance to ALEC headquarters. (Photo: James Cersonsky)“We’re trying to build a movement where black bodies are loved,” said Kelsei Wharton from the Black Youth Project 100, a national group that had its inaugural meeting the weekend of Zimmerman’s acquittal. “We need to vex the quo. We need to get rid of ALEC completely.”

Although it covered similar issues, the next day’s anniversary march was headlined by speakers with notably mixed histories on economic opportunity and racial justice. Attorney General Eric Holder, who oversees record levels of incarceration and surveillance, trumpeted voting rights while gesturing to the “countless others across this great country who still yearn for equality.” Washington Mayor Vincent Gray spoke of the city’s “marginalized citizens” – but didn’t mention the resistance to school closings in black neighborhoods or efforts to persuade him to sign off on living wages for retail workers. And then there was Cory Booker – former banker, mayor-turned-Senate candidate and talk-show regular – who said, “To my generation, we can’t sit back and think that democracy is a spectator sport.”

The elephant on the Mall was the so-called next generation of civil rights activists, who were noted by many speakers but had only a handful of speeches to themselves.

“We need to give them dreams again,” said the Rev. Al Sharpton, the march’s co-organizer, rehashing the hopes of most other speakers. “If we told them who they could be and what they could do, they would pull up their pants and get to work.”

Sharpton’s admonition mirrored the who’s-who, old-guard slant of the march. It’s one thing to advocate for the younger generation. It’s another to treat young people as agents of political change who, long predating the march, have been at work resisting voter suppression laws, Stand Your Ground, incarceration, detention and austerity through base building and direct action. In a new era of racial injustice and class struggle, the charge for civil rights activists is to relight the torch of ’63 by opening space for new voices and new tactics.

Jobs and Freedom

The assembly at ALEC was a mix of students, community activists and young workers. Most of the groups on hand, like their members, are young. Florida’s Dream Defenders emerged in the wake of Martin’s death. Before making international headlines for occupying Tallahassee, the group surrounded Sanford police headquarters, calling successfully for George Zimmerman’s arrest. The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Millennial program emerged from the social insurgencies of 2011, which created an opportunity and a challenge for organized labor to mobilize rank-and-filers and, as the organizers of the 1963 march put it, advance “a broad and fundamental program for economic justice.”

“We saw the Egyptian revolution then what happened in Wisconsin and then Occupy,” says Austin Thompson, 26, the SEIU Millennial program’s founder and lead organizer. “What about young people in the union?”

Amid decades of decline, organized labor has been grappling with how to connect with young people inside and outside its ranks. In 2010, the AFL-CIO launched its first-ever program for young workers, called “Next Up.” Following a founding summit with 400 participants, more than 20 young worker groups have sprung up across union locals and regional councils. Like caucuses for women, queer people and people of color, these groups provide spaces for affinity and issue advocacy. At next month’s quadrennial convention, the federation will vote on a resolution for more Next Up chapters and greater commitment from affiliate unions to issues decided by younger workers, from student debt to immigration to mass incarceration.

Lakesia Collins, center, a nursing assistant from Chicago, joins the anniversary March on Washington. (Photo: James Cersonsky)At SEIU, Thompson envisions Millennial groups as sources of rank-and-file organizing and direct action that can spark broader worker participation. “We all agree that labor unions need to be bigger,” he says. “The question is what bigger means.”

Lakesia Collins, center, a nursing assistant from Chicago, joins the anniversary March on Washington. (Photo: James Cersonsky)At SEIU, Thompson envisions Millennial groups as sources of rank-and-file organizing and direct action that can spark broader worker participation. “We all agree that labor unions need to be bigger,” he says. “The question is what bigger means.”

In Pennsylvania, for example, SEIU’s statewide Millennial committee is focused on student debt, which, as ALEC protesters noted, hits people of color hardest. On August 10, 30 members converged on Comcast headquarters in Philadelphia to call out the connection between the company’s tax breaks and the defunding of public education. “Hopefully we can take a nontraditional union issue – that’s becoming a national issue – and enable people to get involved,” says Greg Riedlinger, a member of SEIU Local 668 who works as a rehab counselor in the city of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. With demographic shifts and the explosion of part-time, low-wage work, “The workforce is different now. What unions are has to change.”

“A lot of people are coming to work, and if they don’t like something, they just quit,” says Lakesia Collins, a nursing assistant from Chicago and member of SEIU Healthcare Illinois. Through young worker organizing, Collins is confident that the culture of work can change. “Getting your own campaigns, your own turnout and to have a label to that, that gives you a lot of work to do.” In Chicago, Millennial organizers plan to use the August 29 fast-food strike as an opportunity to bring new workers into the mix.

With visible organization among young workers to address debt, immigration and racial justice, Thompson says that by the end of next year’s election cycle, “It’s going to force all unions to ask, if young people are doing it, why can’t everyone do it?”

The long civil rights movement

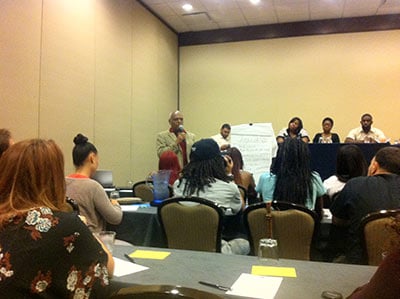

Bob Moses, left, speaks alongside a row of youth organizers. (Photo: James Cersonsky)The day after the anniversary march, youth organizers held a summit to share visions for racial justice. The Dream Defenders and Black Youth Project 100 discussed the political crucible of Zimmerman’s acquittal. Organizers from the AFL-CIO, SEIU and the United Auto Worker’s Global Organizing Institute detailed strategies to elevate the voices of young people of color.

Bob Moses, left, speaks alongside a row of youth organizers. (Photo: James Cersonsky)The day after the anniversary march, youth organizers held a summit to share visions for racial justice. The Dream Defenders and Black Youth Project 100 discussed the political crucible of Zimmerman’s acquittal. Organizers from the AFL-CIO, SEIU and the United Auto Worker’s Global Organizing Institute detailed strategies to elevate the voices of young people of color.

The organizers were joined by civil rights activists from previous generations. Bob Moses, the former field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, recounted meeting Ella Baker, scouting sit-in activity across the South, and organizing wide-scale voter registration. “In 1960, when I walked down the street, no one knew who I was,” he said. “A year later, I walked down the street, and the kids would say, that was a Freedom Rider.”

The civil rights movement of Moses’ era became something for the history books. As the struggle for jobs and freedom has taken new forms, its subjects have sifted out of history – even within the movement’s imagination.

These include the workers of the Black Power–era Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, who, like their predecessors in labor’s golden era, fought for black power within the UAW – the only union to endorse the original march. They also include union caucuses and community groups who actively oppose the entrenched rule of labor and civil rights leaders who spoke at this year’s march.

And then there’s the youngest generation, which has the double fix of declining economic opportunity and a perceived inability to overcome it. As Dream Defenders Executive Director Philip Agnew put it at the march, before his mic got cut off to get to the next speaker, “We are the illegals. We are the apathetic. We are the thugs. We are the generation that you locked in the basement while movement conversations were going on upstairs.”

The next generation may have more debt or uncertainty than its elders, but that doesn’t make it voiceless. At the post-march meeting, older and younger activists emphasized the need for intergenerational dialogue where everyone acknowledges what they know and don’t know.

Come 2063, said veteran labor strategist Bill Fletcher Jr., the test will be, “Have you brought forward younger activists and treated them as leaders and not as chumps?”

Help us Prepare for Trump’s Day One

Trump is busy getting ready for Day One of his presidency – but so is Truthout.

Trump has made it no secret that he is planning a demolition-style attack on both specific communities and democracy as a whole, beginning on his first day in office. With over 25 executive orders and directives queued up for January 20, he’s promised to “launch the largest deportation program in American history,” roll back anti-discrimination protections for transgender students, and implement a “drill, drill, drill” approach to ramp up oil and gas extraction.

Organizations like Truthout are also being threatened by legislation like HR 9495, the “nonprofit killer bill” that would allow the Treasury Secretary to declare any nonprofit a “terrorist-supporting organization” and strip its tax-exempt status without due process. Progressive media like Truthout that has courageously focused on reporting on Israel’s genocide in Gaza are in the bill’s crosshairs.

As journalists, we have a responsibility to look at hard realities and communicate them to you. We hope that you, like us, can use this information to prepare for what’s to come.

And if you feel uncertain about what to do in the face of a second Trump administration, we invite you to be an indispensable part of Truthout’s preparations.

In addition to covering the widespread onslaught of draconian policy, we’re shoring up our resources for what might come next for progressive media: bad-faith lawsuits from far-right ghouls, legislation that seeks to strip us of our ability to receive tax-deductible donations, and further throttling of our reach on social media platforms owned by Trump’s sycophants.

We’re preparing right now for Trump’s Day One: building a brave coalition of movement media; reaching out to the activists, academics, and thinkers we trust to shine a light on the inner workings of authoritarianism; and planning to use journalism as a tool to equip movements to protect the people, lands, and principles most vulnerable to Trump’s destruction.

We urgently need your help to prepare. As you know, our December fundraiser is our most important of the year and will determine the scale of work we’ll be able to do in 2025. We’ve set two goals: to raise $136,000 in one-time donations and to add 1440 new monthly donors by midnight on December 31.

Today, we’re asking all of our readers to start a monthly donation or make a one-time donation – as a commitment to stand with us on day one of Trump’s presidency, and every day after that, as we produce journalism that combats authoritarianism, censorship, injustice, and misinformation. You’re an essential part of our future – please join the movement by making a tax-deductible donation today.

If you have the means to make a substantial gift, please dig deep during this critical time!

With gratitude and resolve,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy