It’s Saturday afternoon in December 2017 at the hotel workers’ union hall in Stamford, Connecticut, a mere two days before a scheduled union election at the Hilton Stamford. Where one would expect nerves and chaos, a quiet calm covers the hall. American unions have struggled for decades to successfully organize non-union workers, with the movement’s difficulties organizing workers only intensifying. Notwithstanding a recent small uptick amongst white-collar workers and scattered victories, unions have been unable to figure out how to organize US workers en masse. Recent high-profile election losses, much of the labor movement choosing not to even attempt elections and some unions beginning to experiment with minority unionism all evidence this struggle. The Hilton Stamford workers were attempting where many are failing and decreasingly few are even attempting.

The 130 workers of the Hilton Stamford faced all of the familiar challenges: The majority Haitian-immigrant workplace faced great legal intimidation in the form of Trump’s elimination of Temporary Protected Status, hotel ownership spent upwards of $1 million on a vicious union-busting campaign (including contracting Trump’s personal anti-union consultant and armed guards to patrol the hotel), and hotel ownership ran roughshod over the workers’ organizing rights throughout the campaign.

Nevertheless, pre-election Saturday afternoon at the hotel workers union hall was uncomfortably comfortable. Two days later, the workers’ confidence proved well founded, as Hilton Stamford workers obliterated the company’s anti-union campaign in voting 110 to 5 for the union.

Beyond the life-changing victory for the workers and their families, the Stamford hotel workers used an organizing formula different from anything most unions use today, ferociously overcoming the challenges most unions face. Victories are occurring elsewhere and tests still remain for the Stamford workers, but the sheer scale and ferocity of their victory indicates that how these workers bucked the trend holds unique insight into reversing American unions’ fortunes.

A flyer of Stamford Hilton housekeeper Ismanie Dat distributed amongst workers in response to the company using armed guards to patrol the hotel to intimidate workers. All flyers were created by volunteer workers. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

A flyer of Stamford Hilton housekeeper Ismanie Dat distributed amongst workers in response to the company using armed guards to patrol the hotel to intimidate workers. All flyers were created by volunteer workers. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

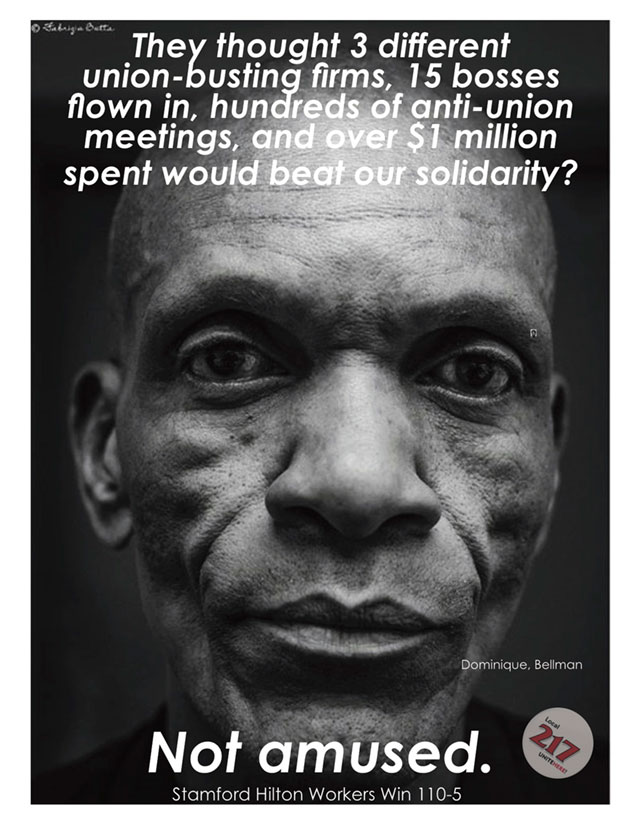

A flyer of Stamford Hilton bellman Dominique Jean Pierre distributed amongst workers after their election victory. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

A flyer of Stamford Hilton bellman Dominique Jean Pierre distributed amongst workers after their election victory. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Unions’ Organizing Challenge: External or Internal?

Unionists and academics frequently debate the cause of American unions’ declining size and their difficulties organizing, but the explanations typically given do not hold up under a bit of scrutiny. Most blame external forces beyond unions’ control, bemoaning the lack of legal protections for workers attempting to organize, the intensity of employers’ anti-union campaigns, or bad economic conditions that make organizing perilous. The problem with these explanations is that these conditions existed even more intensely at times when unions successfully expanded in the past.

Union leaders today decry the intensity of companies’ anti-union campaigns, particularly the widespread use of “union avoidance” consulting firms. Yet, today’s anti-union campaigns pale in comparison to the mass bloodshed, espionage and blacklisting workers overcame to organize in the 1930s. The hundreds of workers shot dead in successful organizing struggles in the 1930s certainly at least matches the intensity of today’s anti-union campaigns.

Union leaders today decry that employers run roughshod over workers’ rights enshrined in the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). Yet it was the hundreds of thousands of industry workers who organized (without any such legal protections in the first place) in the early 1930s prior to the NLRA that forced its passage in the first place — not to mention that involvement of “the law” during several previous organizing booms typically meant forceful repression from local police or the State and National Guard, much less enforcement of any organizing rights.

Union leaders today decry the precarious economic conditions facing workers and the difficulties of moving them to action with unemployment high and no safety net. Yet unions made perhaps their greatest organizing leap in the years immediately following the greatest economic crisis in the nation’s history.

Convinced of the notion that the obstacles to mass organizing are beyond their control, many unions have resorted to experimenting with campaigns that seek to win union recognition without substantial worker organization, such as the SEIU’s high-profile and oft-celebrated fast-food worker campaign, which does not even attempt to mobilize a majority of workers in any workplace. Despite some scattered campaign victories, unions have been unable to generate the type of growth and movement needed to challenge the corporate stranglehold on US society through strategies based on things other than worker power, such as legislation, public relations, corporate research, etc. Try as they may to skirt the issue, the labor movement is unlikely to find a substitute for the irreplaceable core of workers’ power: collective action of a critical majority of workers in a workplace or industry. Fortunately, if workers overcame such challenges in the past, they can do so now as well.

If the outside forces confronting unions aren’t particularly new, something new within unions likely developed to make mass organizing stagnate. In this light, the Stamford hotel-workers union looked inwards to figure out how to organize more workers. Union leadership assessed that what’s changed since labor’s explosive organizing was a basic organizing formula: Instead of large groups of union workers going to organize even larger groups of non-union workers, unions came to depend on much smaller teams (or even individuals) of paid staff-organizers attempting to organize large groups of non-union workers. As American unions grew mid-century and established greater institutional footing, they also began to become more heavily bureaucratized and consequently more staff-driven; this applied to all facets of the union, but markedly bled into unions’ new organizing programs. The new formula of staff-driven organizing campaigns is plagued by obvious problems, such as a typically higher worker-to-organizer ratio, issues of “relatability” between organizers and non-union workers, and greater susceptibility to company propaganda that paints the union as a “third-party” or a business. Perhaps unsurprisingly, labor has made no significant leaps in size since the new formula has become commonplace, and Stamford’s hotel-workers union looked to change it.

Hilton worker committee along with Hyatt workers hold one of their weekly meetings to plan campaign tactics. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Hilton worker committee along with Hyatt workers hold one of their weekly meetings to plan campaign tactics. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Stamford Hilton room service server Jaime Alvarez alongside his coworkers and Hyatt workers informs hotel management of their intent to unionize. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Stamford Hilton room service server Jaime Alvarez alongside his coworkers and Hyatt workers informs hotel management of their intent to unionize. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Looking Inward: How Unions Can Change Their Organizing Formula

To organize the non-union Hilton Stamford, instead of relying on paid staff organizers, the union turned to rank-and-file members from nearby union workplaces. Shop stewards from the Hyatt Hotel and Royal Bank of Scotland cafeteria workforce, already members of the hotel workers’ union local, conducted an overwhelming majority of the organizing meetings, predominantly house calls to the non-union Hilton workers. Rather than simply riding along as sidekicks to a staff organizer, the volunteer rank-and-file organizers led the organizing visits and held responsibility (“turf,” in organizing parlance) for meeting weekly with non-union Hilton organizing contacts. Nearly 20 rank-and-file members of the union accepted responsibility for meeting weekly with a handful of the non-union workers respectively, convening in the union hall once a week to discuss how the previous week’s organizing meetings went and plan the next week’s meetings. Every evening, union stewards met at the union hall, paired up and dispatched out to the living rooms of non-union workers. The stewards strategically took responsibility for those non-union workers with which they had most in common. Union housekeepers visited non-union housekeepers to discuss the union and next steps, Haitian union members visited Haitian non-union workers, cooks visited cooks, Colombians reached out to Colombians, bellmen talked to bellmen, and so forth on a weekly basis.

The results were explosive. Within only a few months, the organizing team of rank-and-file members with little previous experience in non-union organizing built a rank-and-file committee in the Hilton Stamford of nearly 30 workers and signed up over 85 percent of the Hilton workforce on union membership cards. The causes of their success were clear: The rank-and-file union members easily built trusting connections with the non-union workers who came from similar backgrounds, did the exact same work every day and often even lived in the same neighborhoods. The non-union Haitian bellman from the Hilton more quickly confided in the Haitian bellman from the unionized Hyatt, and the trust necessary to commit to a risky organizing drive developed far more easily than it may have with a white staff organizer with no experience working in a hotel. Organizing conversations transitioned smoothly from commiserating about the difficulties of particular hotel jobs, to the challenges of immigration, to the need to make sacrifices to win the union. Moreover, the sheer numbers of organizers in the field were much greater than usual for the union. With nearly 20 rank-and-file volunteer organizers visiting the non-union workers every week, the ratio of organizer to worker was much better than what unions can typically afford to staff, and made crucial organizing visits with the non-union organizing committee more frequent.

Stamford Hilton cook Irwin Martinez alongside coworkers and Hyatt workers informs hotel management of their intent to unionize. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Stamford Hilton cook Irwin Martinez alongside coworkers and Hyatt workers informs hotel management of their intent to unionize. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

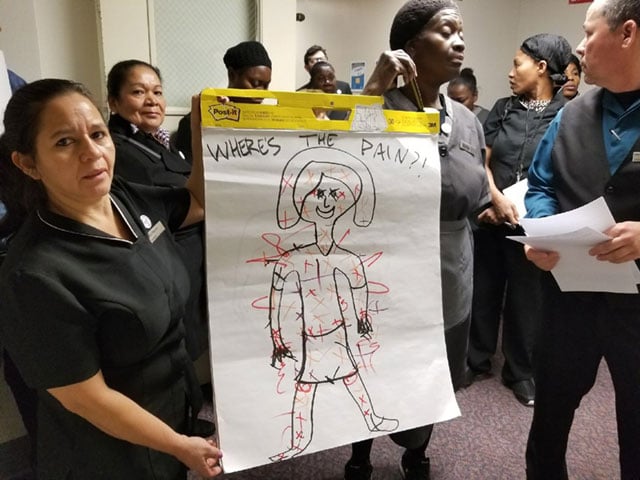

Stamford Hilton housekeepers deliver a poster to hotel management illustrating where their bodies feel pain due to excessive workloads as one of their daily actions. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Stamford Hilton housekeepers deliver a poster to hotel management illustrating where their bodies feel pain due to excessive workloads as one of their daily actions. (Photo: Unite Here Local 217)

Many union campaigns begin strong but quickly crumble under the weight of high-powered and sophisticated anti-union campaigns. Yet due to the union’s altered organizing formula, when the Hilton Stamford ownership invested millions of dollars to persuade the workers to vote against the union, none of the company’s anti-union propaganda worked. Despite hiring notorious “union avoidance” consultants Cruz and Associates, Donald Trump’s personal union-busters of choice at his hotels, as well as flying in over 20 managers, consultants and lawyers to live in the hotel and meet daily with each worker, none of the anti-union propaganda had any influence on the Hilton workers. The typical anti-union tropes that paint the union as a “third-party,” a business, or as simply wanting the workers’ dues money was hardly persuasive to workers who understood the union as the rank-and-file union members who’d been visiting them in their homes. Surely the housekeeper from down the block, from the same country, who performed the same job daily was in no way a business simply out for non-union workers’ money. The rank-and-file volunteers lacked most of the formal training of the highly professionalized staff organizer most common in unions today, but proved equally, if not more, effective. Despite an anti-union campaign even more enormous and lawbreaking than unions usually face, the Hilton Stamford workers voted to join the union with 96 percent of the vote.

If the outcome seems obvious given the number of rank-and-file volunteer organizers, less obvious may be how the union was able to generate so many volunteer organizers. This question is perhaps most important, given a changing political leadership amongst many unions where obstacles to rank-and-file involvement are less ideological and more practical. While many unions initially bureaucratized at the behest of conservative, self-serving leadership, many progressive unions today would like to reconfigure their organizing formula with more rank-and-file volunteers but face challenges doing so. Long removed from the rank-and-file upsurges of the 1930s and 1940s, most union staff and members today have only known the top-down, staff-driven model commonplace today. Despite a growing desire to reinvigorate membership participation, old habits are difficult to break, and most unions (staff and members) operate with the expectation that organizing is primarily the responsibility (and best done) by paid staff. Breaking these expectations, hardened by decades of repetition, is a difficult task.

The Stamford hotel workers union sought to reinvigorate rank-and-file organizing by reviving two practices that have been systematically sucked out of unions for decades, but that were foundational in the great labor upsurge that built the modern movement: militancy and democracy.

For example, at the inaugural United Automobile Workers convention in 1935, a meeting of rank-and-file organizers from around the country would propel American unions from their deathbed in the early 1930s to organizing over one-third of all American workers in just two decades. The pre-convention program published called for three central things: “militant action,” a “democratically controlled convention” with “free elections from the floor of a chairman and all committees by majority vote,” and “confidence in the organized power of labor.”

Believing in the twin pillars of democracy and militancy was one thing, but the more difficult task for the Stamford hotel workers was figuring out concretely how to implement them organizationally.

Prior to descending upon the non-union workers, the union began by focusing on the existing membership, implementing as democratic and militant a program as possible internally. Union leadership banked that if members felt real ownership of their organization, they would be more likely to take ownership of the organizing — but workers wouldn’t take ownership if their daily experience was that they had no actual ownership within the union. Thus, the union ran weekly stewards’ meetings where nearly everything was voted upon, no matter how minute.

“We voted on the weekly agenda, then on every single agenda item before moving on,” said Chief Shop Steward Dennis Fiore. “Some votes felt silly at times [if] the issues were so small or obvious, but if someone put it on the agenda, we figured it wasn’t silly to someone, and everyone’s opinion in the union is important.”

From what type of shop floor action to take to what type of union apparel to purchase, rank-and-file members were handed the reins for nearly all decisions that had previously been made exclusively by staff. Modern unions often rhetorically tell workers “they are the union” without actually letting them be the union and drive the organization. This changed with the Stamford hotel workers in exaggerated form, with an eye on speeding up the process of moving rank-and-file organizers into the non-union organizing.

Similarly, if members felt real day-to-day power on the shop-floor, the union posited, they would feel real incentive to take part in building that power by organizing. Shop-floor militancy, in the form of workplace actions to resolve everyday problems, built that sense of power. Most modern unions have allowed the grievance-resolution process to become heavily bureaucratized, with staff navigating a complex web of contractual and legal procedures in a lawyereqsue fashion alienating to the average worker. While issues can and are won for members in this arrangement, the system by design takes the struggle away from the shop-floor and the power out of the hands of the worker. Similar to the democracy strategy, the union implemented an issue resolution program focused on shop-floor action (rather than legalistic contract enforcement) in an exaggeratedly intense form. Every issue merited a workplace mobilization, with grievance meetings becoming nothing more than an arena for mass demonstrations. Soon, workers established a culture where workplace problems meant workers were expected to organize actions, rather than commence the legalistic, slow and physically-removed grievance procedure.

“After a little while, it just became the system,” said banquet server and shop steward Francisco Tobias. “If someone had an issue, we knew the only solution was to mobilize an action. We mobilize … over every little issue, but that’s the union.”

Not only were more issues resolved faster, but workers developed a deeper belief that the union was themselves rather than the staff, and that the power of the union lay with the workers rather than a contract — crucial developments in the union’s push to have the workers lead non-union organizing.

Emboldened by their newfound power within both the union and the workplace, the rank-and-file leaders of the union were primed to organize non-union workers nearby. When union staff pushed shop stewards to take responsibility for the organizing, they understood that they were the union leaders who had to do it and felt a compelling incentive to do so. It was internal democracy and militancy that led to rank-and-file members’ commitment to organize the unorganized, and the new organizing formula led to rapid results.

What the Stamford Model Can Teach a Labor Resurgence

The lesson from the Stamford hotel workers is that unions must return to their roots as worker organizations — member-run and member-powered. The organizing cliché that “there are no shortcuts” applies in the most fundamental sense; no amount of staff expertise or clever strategy will succeed in rebuilding the labor movement so long as unions remain more like service organizations than actual worker-run organizations. Politics, public relations and corporate research — the focus of most current staff-heavy union efforts toward a resurgence — can supplement mass worker mobilization, but can never replace it as the spine of union power.

To begin a real process of rebuilding and growth, unions must first look internally as the Stamford hotel workers’ union did. Without a democratic and militant internal organization, unions will continue to be unable to mobilize the number of rank-and-file organizers needed to create a real movement.

Moreover, without a democratic and militant internal organization, unions could grow their membership and still be weak, as the labor movement’s lack of internal democracy currently leaves it unable to mobilize a significant portion of its membership. American unions still have nearly 15 million members; it is not difficult to imagine the potential influence labor could wield if capable of mobilizing merely half of that membership in a general strike or march on Washington. When Gov. Scott Walker essentially outlawed public-sector unionism in Wisconsin and unions either did not or could not fight back with a significant strike, what was already obvious should have become unavoidably clear: Labor’s internal petrification has left it unable to mobilize its own members, its ultimate weapon in both action and organizing. If unions couldn’t strike with their heads on the chopping block, when could they?

Yet, the ultimate lesson from the Stamford hotel workers is one of hope. If unions can figure out how to mobilize their members to organize non-union workers, the formula is explosive, since the conditions for workers in this country are increasingly atrocious. Nothing corporations and their political lapdogs can do in this country can eliminate the reality that they depend entirely on workers for their wealth. With still nearly 15 million members, a turn inwards to reorganize their ranks could yield unions a huge army of workers in the streets and in the living rooms of non-union workers. A democratic and militant worker organization overwhelmed the wealthy elite and built a vibrant labor movement once before in this country, and as the Stamford hotel workers showed, it can be done again today.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.