Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

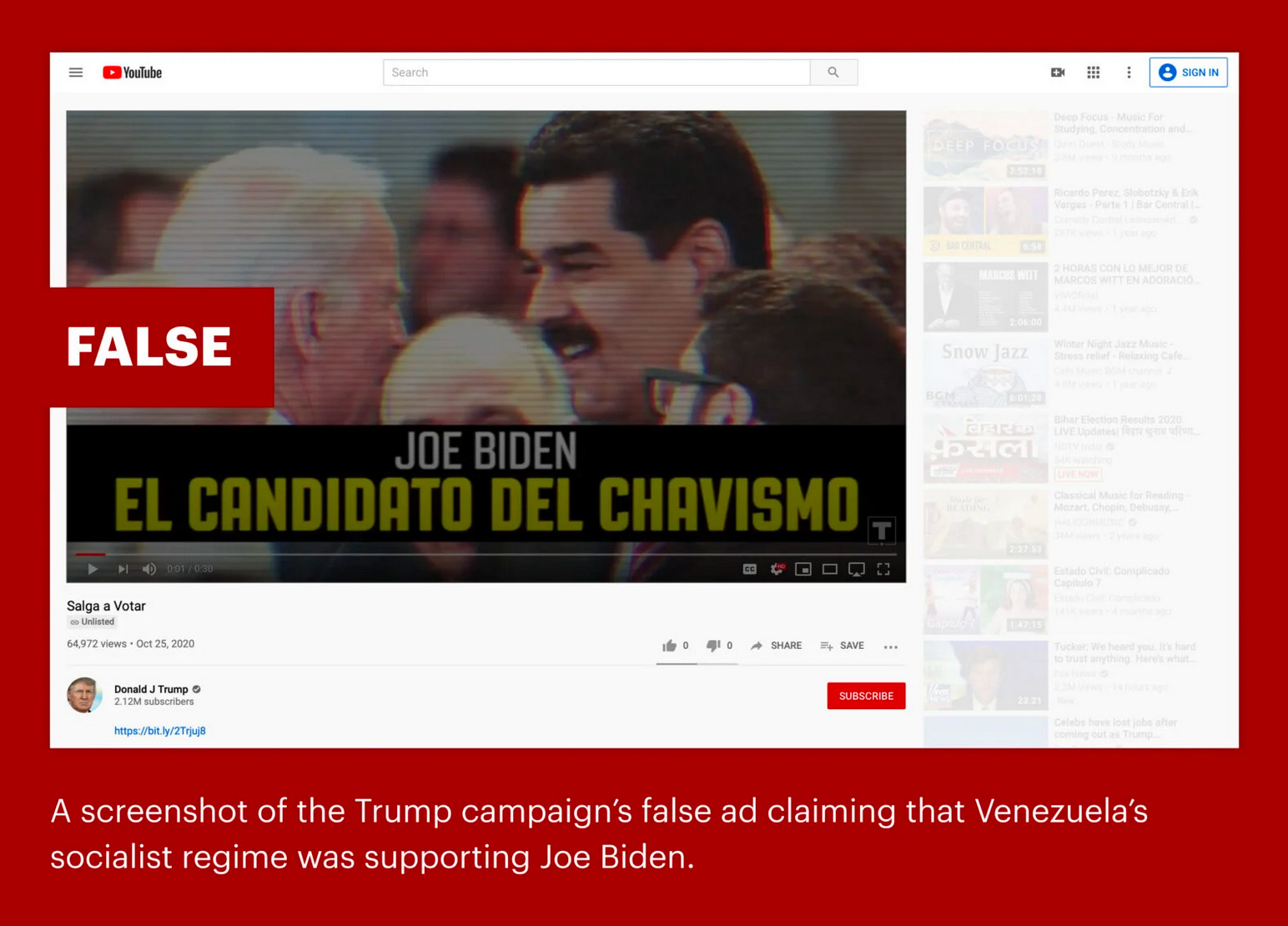

In Florida, where President Donald Trump gained crucial support among Latino voters, his campaign ran a YouTube ad in Spanish making the explosive — and false — claim that Venezuela’s ruling clique was backing Democratic nominee Joe Biden.

YouTube showed the ad more than 100,000 times in Florida in the eight days leading up to the election, even after The Associated Press published a fact-check debunking the Trump campaign’s claim. Actually, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro expressed opposition to both presidential candidates.

The video was part of a broader Trump campaign strategy in heavily Latino South Florida that sought to tie Biden to Socialist leaders like Maduro and the late Cuban President Fidel Castro. Trump won Florida by about 375,000 votes, the largest margin in a presidential election there since 1988. He carried about 55% of the Cuban American vote, according to exit polls by NBC News.

“Latinos who live here in the U.S. have left socialist or communist regimes,” said Diego Scharifker, a Venezuelan American lawyer, former city councilor in Caracas and co-founder of the pro-Biden group Venezolanos Con Biden. “There is of course a big impact or fear or scarring in the Latino community in the U.S. from communism. Trump with his false accusations and false information was fearmongering and playing on the pain to promote his agenda.”

The ad illustrates gaps in the policing of misinformation by Google, which owns YouTube. While Google nominally prohibits all false claims in advertising, it rarely takes down political ads. In addition, shortcomings in its transparency tools make it harder for watchdogs and fact-checkers to scrutinize ads.

Google’s political ad rules are “trying to have it both ways” with respect to fact-checking, said Bridget Barrett, a political communication researcher at the University of North Carolina. “In reality, basically everything stands.” Google sees claims like the one about Maduro as being “within the public arena that should be contested by Biden’s campaign or fact-checked by journalists,” Barrett added.

YouTube approves ads by both human and machine review. Its policies prohibit any advertiser from making “a false claim — whether it’s a claim about the price of a chair or a claim that you can vote by text message, that election day is postponed, or that a candidate has died.”

Charlotte Smith, a company spokeswoman, told ProPublica in an email that “we don’t make any special exceptions for politicians.” Nevertheless, YouTube takes down only a “very limited” number of political ads making “demonstrably false claims that could significantly undermine trust in democratic or electoral processes,” she said.

The Trump campaign ad “doesn’t meet that bar,” she said. “This video does not violate our policies. … Political ads are known for being hyperbolic, and we’re not going to attempt to adjudicate every claim or counterclaim.”

Other platforms are at least somewhat more restrictive. While Facebook doesn’t fact-check campaign ads, it banned new ones within a week of the election. (The Trump ad does not appear to have run on Facebook, according to its ad library. If it had, the ban may not have applied to it, because it began running on YouTube on Oct. 26, eight days before the Nov. 3 election.) Facebook’s fact-checking partners do vet ads by political action committees and other third-party groups, some of which get removed. Twitter banned all political advertising. Although broadcast television stations aren’t allowed to choose candidate ads by content, cable networks can, and sometimes do, reject ads. The Trump ad didn’t appear on TV, according to Advertising Analytics, an ad-tracking firm.

The Trump campaign saw YouTube as a key to its strategy, according to a Politico report in September. It ran more than 18,000 video ads on YouTube this year. The campaign spent $106 million, including $37.2 million in the last month of the campaign, on Google’s platform, including both YouTube ads and Google search ads.

The questionable video begins by describing Biden as “the candidate of Chavismo,” referring to the brand of socialism associated with Hugo Chávez, the late leader of Venezuela, and Maduro’s government. It then shows Diosdado Cabello, a Maduro ally and Venezuela’s second-most powerful politician, saying on his television program that the “brisa Bolivariana,” or the “Bolivarian breeze” of Latin American socialism, “is blowing, blowing, blowing, blowing. … Let’s see what happens. Maybe the Bolivarian breeze will reach the United States. In how much time? In 13 days until the elections.” The term “Bolivarian” is an allusion to Simón Bolívar, the 19th-century revolutionary, claimed as an inspiration for many Latin American socialist movements.

Then the text on the screen reiterates that “the Chavistas” — the political party that controls Venezuela — “want Joe Biden to win.” The video concludes with a statement that it was paid by the Trump campaign and Trump saying that he approved the message.

There’s little doubt that the relationship between the Trump administration and the Maduro government is tense. Trump has imposed sanctions on Venezuela and on Maduro and Cabello personally. The U.S. government indicted both Maduro and Cabello on narco-terrorism and drug trafficking charges in March. Venezuelan state-run television has struck a “completely anti-Trump” tone, said Daniel Acosta-Ramos, an investigative researcher at First Draft, a nonprofit that tracks misinformation and an Electionland partner.

Yet Maduro said in late September that he didn’t care who was elected. “If Trump wins the elections, we will confront him and defeat him, and if Biden wins, we’ll confront him and defeat him too,” he said. An AP fact-check of a video that resembles the one in the Trump campaign ad concluded that neither Biden nor Maduro “has declared that there is any kind of affinity between them or between their national projects.”

In the television segment from which Cabello’s “Bolivarian breeze” remark was clipped, he didn’t explicitly mention Trump, Biden or the Democratic or Republican parties. While the remark could be interpreted as hoping that Biden would be elected and promote the agenda of his party’s progressive wing, Cabello has a reputation for being a provocateur and saying unclear things on purpose, according to Acosta-Ramos. “That ambiguity creates an environment ripe for misinfo,” he said.

The ad, Acosta-Ramos said, was “micro-targeted for people who know what the ‘brisa Bolivariana’ means. Not just Venezuelans, but also Cubans and Colombians.”

Other YouTube ads from the Trump campaign reinforced the false message. They showed clips of Maduro referring to Biden as “Comrade Biden” in a 2015 speech. Although it was only a passing reference, and Maduro accused Biden shortly afterward of plotting to overthrow him, Donald Trump Jr. framed it as evidence that Biden was weak on socialism.

The Trump campaign’s official bilingual Twitter account also claimed that Maduro’s regime supported Biden. A tweet from President Trump called Biden a “PUPPET of CASTRO-CHAVISTAS.” Trump ads on Facebook called Biden a “socialist” and pictured him with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Bernie Sanders, both of whom refer to themselves as democratic socialists.

“There was a concerted effort by the Trump campaign and their allies to misrepresent Joe Biden and his values because they knew they couldn’t win on Trump’s disastrous record,” a Biden campaign official told ProPublica.

Florida’s Venezuelan population has grown to about 200,000, of whom an estimated 50,000 are registered to vote. In Doral, a city in Miami-Dade County that’s home to many Americans of Venezuelan, Cuban and Colombian descent, Trump pulled in roughly 49% of voters in 2020, up from 29% in 2016. Overall, in Miami-Dade, Trump garnered nearly 200,000 more votes than he had in 2016, shaving the Democratic margin from 29% to 7%.

The Trump campaign, the White House and the Venezuelan Embassy did not respond to requests for comment.

The Trump ad may have attracted relatively little notice during the campaign because of inadequacies in the political ad report that Google established in 2018 to improve transparency. Unlike Facebook’s political ad archive, Google’s doesn’t group identical ads together if, for instance, they were shown over different time periods. Google’s transparency tools showed three different copies of the “brisa Bolivariana” ad, giving separate data for each. Google also doesn’t make videos searchable or any ad content downloadable in bulk.

The design doesn’t allow opponents, journalists or watchdogs to meaningfully analyze the 263,000 political video ads (and 361,000 other ads) that Google sold in 2020, Barrett said.

“You’re just drowning in content and overwhelmed by these individual pieces of advertising content, and really many of them are the same, you’re stuck trying to swim through this overwhelming sea of ads,” Barrett said. Ads “can disappear into the depths of the ad library.”

Google has said that it only allows advertisers to target political ads by users’ location, age and gender, and that it discloses these targeting choices on its transparency website. The three copies of the “Bolivarian breeze” ad were targeted by location to Florida users.

Although it’s not disclosed in Google’s transparency tools, YouTube ads also may be targeted by language, for example to Spanish speakers, Smith said.

It’s unclear exactly how much the Trump campaign spent on the ad and how many times it was shown. Google’s data show that the Trump campaign spent between $1,000 and $5,000 on one copy of the ad; between $100 and $1,000 on another; and less than $100 on the third. Two of the copies were shown fewer than 10,000 times, and the third was shown between 100,000 and 1 million times. Facebook publishes more precise information.

Trump supporters amplified the campaign’s message, professing to connect Biden and other Democrats to “Castro-Chavismo,” a term linking Venezuelan socialism to Cuba’s. False posts on social media, of undetermined origin, purported to show Jill Biden, Joe’s wife, standing next to Fidel Castro. It was actually Jacqueline Beer, the wife of a Norwegian explorer.

“We saw a huge number of WhatsApp messages being shared in Venezuelan, Cuban groups, saying the governments of these countries that we escaped, [they] want Biden — so we should vote Trump,” Acosta-Ramos said.

What a Biden staffer described as a flood of information put the Democrat’s campaign on the defensive. The Biden campaign mounted its own fact-checking effort to push back against the claims about Biden and socialism. It invested heavily in outreach to Florida Latinos, including six-figure media buys in the last two weeks of the campaign targeting the community, a staffer said. At an early October rally in Miami, Biden said, “Maduro, who I’ve met, is a dictator, plain and simple, and he’s causing incredible suffering among the Venezuelan people.”

Ronny Rojas of Telemundo, Derek Willis and Ivette Leyva contributed reporting.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.