When I was working on my most recent anthology, Between Certain Death and a Possible Future: Queer Writing on Growing Up with the AIDS Crisis, I received a submission from Keiko Lane about joining ACT UP and Queer Nation in Los Angeles as a 16-year-old Okinawan American lesbian in 1990. That piece, an excerpt from Lane’s memoir-in-progress, became the first chapter of the anthology because it immediately grounds you in the moment — protesting against Christian fundamentalists, arguing about politics and identity and assimilation, life and death intertwined in one another’s arms. Not just that, but it offers a generational view of coming of age in the midst of the AIDS crisis, and internalizing the trauma as part of becoming queer. Fighting to survive, even as survival feels impossible.

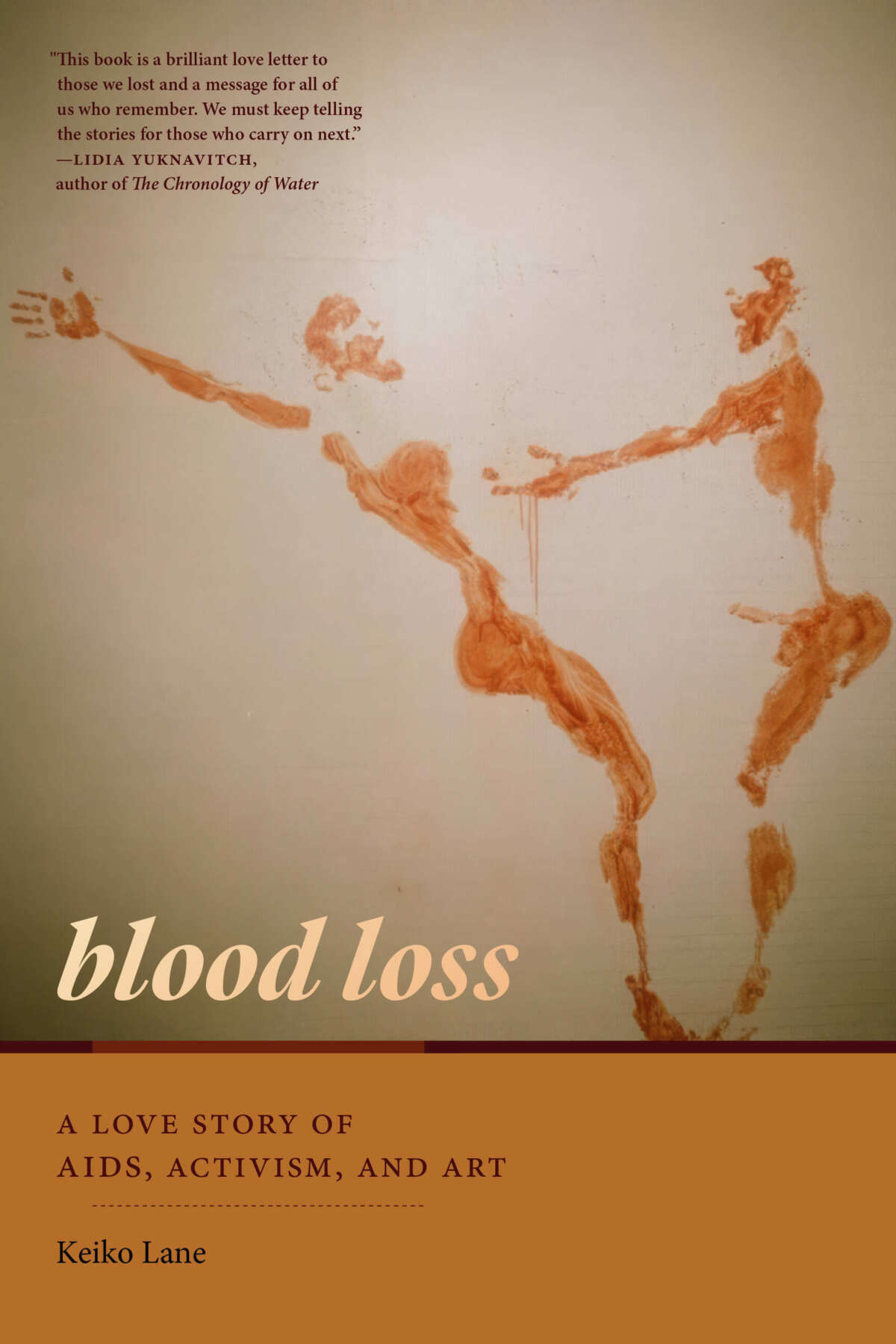

“There is no before,” Lane writes in her new memoir, Blood Loss: A Love Story of AIDS, Activism, and Art. “We want to imagine that there will be a time after. But there won’t be.” This is a book about brave and desperate acts of care, the necessity and impossibility of memory, and how time refuses closure. It differs from other AIDS activist memoirs not just in terms of perspective, but through its vulnerability, its openness to the porousness of experience, its drive to articulate the inexpressible.

This interview engages with the perilous quest for embodiment that is central to the book — the search for truth, the demand for accountability, the making of self and sensibility, and the collective struggle that forms an activist life. Lane talks about coalitional politics, shifting activist strategies in a time of crisis and creating an unconventional form for a multifaceted story. She challenges simplistic rhetoric about strength and persistence, and reveals the complications of intimacy and disclosure in a time of loss that continues into the present.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore: The book opens with an all-night vigil and participatory performance that you attended on World AIDS Day in 1990, when you were 16. Legislative threats of quarantining all HIV-positive people bring to mind your Okinawan American family’s incarceration at Manzanar during World War II. I wonder if you could talk about this intertwining legacy of trauma and how it affected you as you became an AIDS activist.

Keiko Lane: At the time of that vigil, I had been in activist spaces for a few years. I was starting to understand the political and historical overlaps between World War II incarceration and the attempts in the ‘80s, ‘90s — and still — to criminalize bodies that don’t fit the white, upwardly mobile, heteronormative vision of neoliberal late capitalism. But in the process of writing Blood Loss, I really had to come to an understanding of the affective and embodied legacy of both experiences. The resonance between them became clearer as I felt back into my experiences of loss and trauma in ACT UP at the same time as I was doing more research into my family legacies of incarceration, migration and separation.

The process of working on the memoir was a process of moving away from the political analysis of the ACT UP and Queer Nation years, and allowing myself to feel and grieve. The aftermath leaves me obsessed with the proximity of my loved ones, the importance of telling stories and remembering, and the attempts to save and protect the people I love.

Both ACT UP and Queer Nation articulated an anti-assimilationist queer politic that refused conformity to straight norms, and built camaraderie on difference, whereas you grew up thinking that assimilation as an Okinawan American was necessary for survival.

My activism before ACT UP and Queer Nation had been a kind of hiding. A notion that if I could make the world safe for others, then it might be safe for me. An unconscious strategy that being supportive but not visible also means less likelihood of being targeted, which is an assimilationist stance. Once I came into Queer Nation, I was suddenly in a community of radical folks who were willing to fight for me, to make things safe for me. That empowered and trained me to be willing to put myself on the line for them.

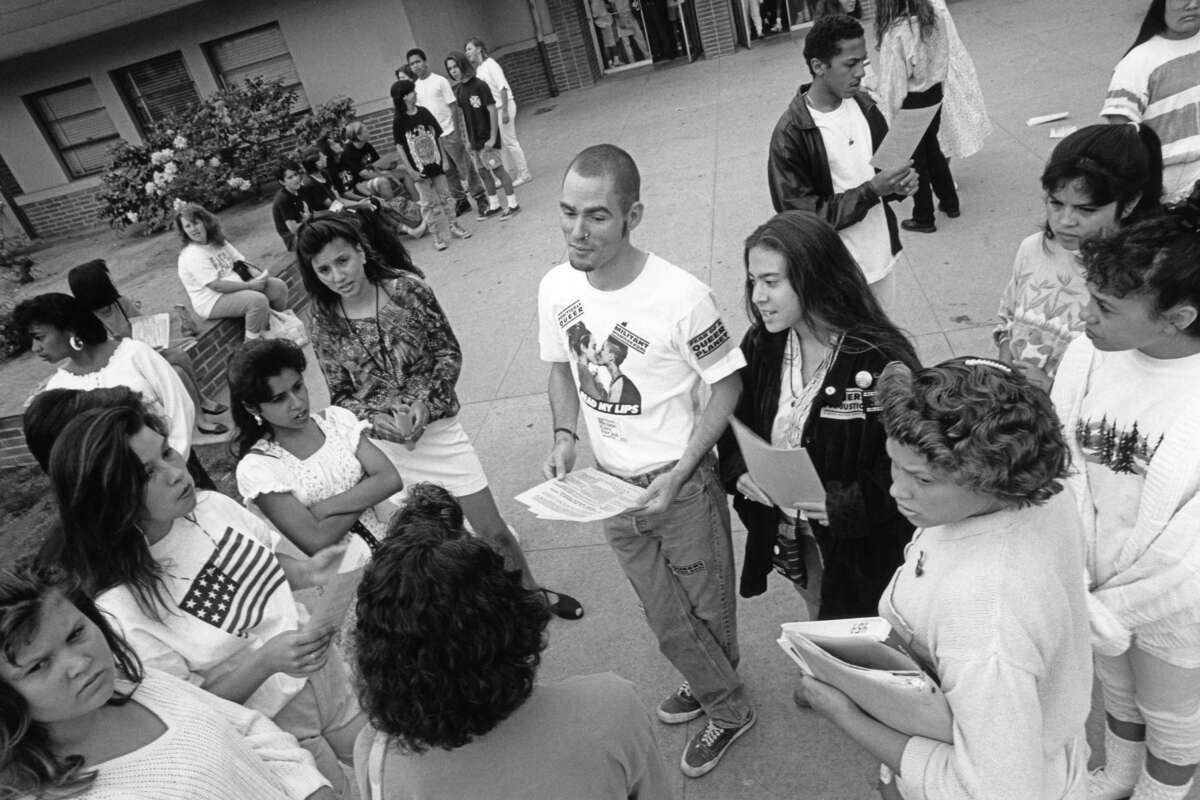

As a young person, I was also a lightning rod for older queers’ fantasies and projections of what it would have been like to have mentorship and support as a young queer. So, the experiences of condom distribution at high schools, picketing and holding news conferences to support queer teachers whose jobs were threatened for teaching explicit and explicitly useful sex and health education, were occurring simultaneously with my experiences of being harassed and threatened with violence by my high school’s security guards because of my visible queerness. But in those Queer Nation years, I also knew that I would be taken care of. Protected.

Precarity is structural: Who is culturally, politically empowered or expected to survive, and who is set up to be sacrificed?

In the stories told in family or community about incarceration, there was never anyone outside of the camp experience who was fighting for us. There were guards and there were internees. There was no feeling of alliance, of mutual stake in survival. So, the juxtaposition between this legacy and the sense of mutuality and alliance was a kind of culturally embodied, reparative experience. What is activism but a kind of mutual aid?

These weren’t gentle, slow, easily integrated lessons. They were hard and fast, sometimes learned in the instant of witnessing who body-blocked an LAPD officer’s baton from striking vulnerable community members. Sometimes being the person protected. Sometimes being the person doing the protecting.

You write, “The idea that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger is bullshit. They aren’t opposite, don’t cancel each other out…” As a member of ACT UP when so many people were dying of AIDS, how did grief and loss complicate and expand the possibilities for mobilization?

Fury can be a catalyst. At the same time, grief can lead to inaction. I’m pretty sure our nervous systems still haven’t recovered. We did our best to coax each other out of this immobilization. We also tried to gently steer each other to safety.

Who has the privileges to take which risks or express in which ways? Or, another way to look at it: Who has nothing left to lose? We also became each other’s thing to lose. We kept each other connected. We tried to notice who had the energy for which kinds of tasks, or who needed which kinds of care. I don’t want to romanticize it. We certainly were imperfect. And rage and grief amplify the chaos of imperfection.

How do people love, how do people grieve, how are we insistent on connection in spite of, or because of, the precarity of connection? Precarity is structural: Who is culturally, politically empowered or expected to survive, and who is set up to be sacrificed? And precarity is also internal and emotional. How do we insist on connection in spite of the ongoingness of traumatic loss? And how do we survive the moments when we walk away from connection? What happens after that?

When you write, “We moved against the respectability politics of elegant victimhood and gestured toward an erotics of fury and risk,” I think erotics is a key word because so much of the book is about your deep, intimate relationships in ACT UP — you write, “Dykes and fags sleeping together doesn’t negate queerness; it amplifies it.” This notion is central to the book, and one of the things that distinguishes it from other AIDS activist memoirs.

That line may be the line I get asked about most. When I wrote it, it was one of those lines that I wrote without thinking — those magic lines that sometimes just appear when we get out of our own way. And then I read it again and thought, Oh shit, people are going to have a reaction to this.

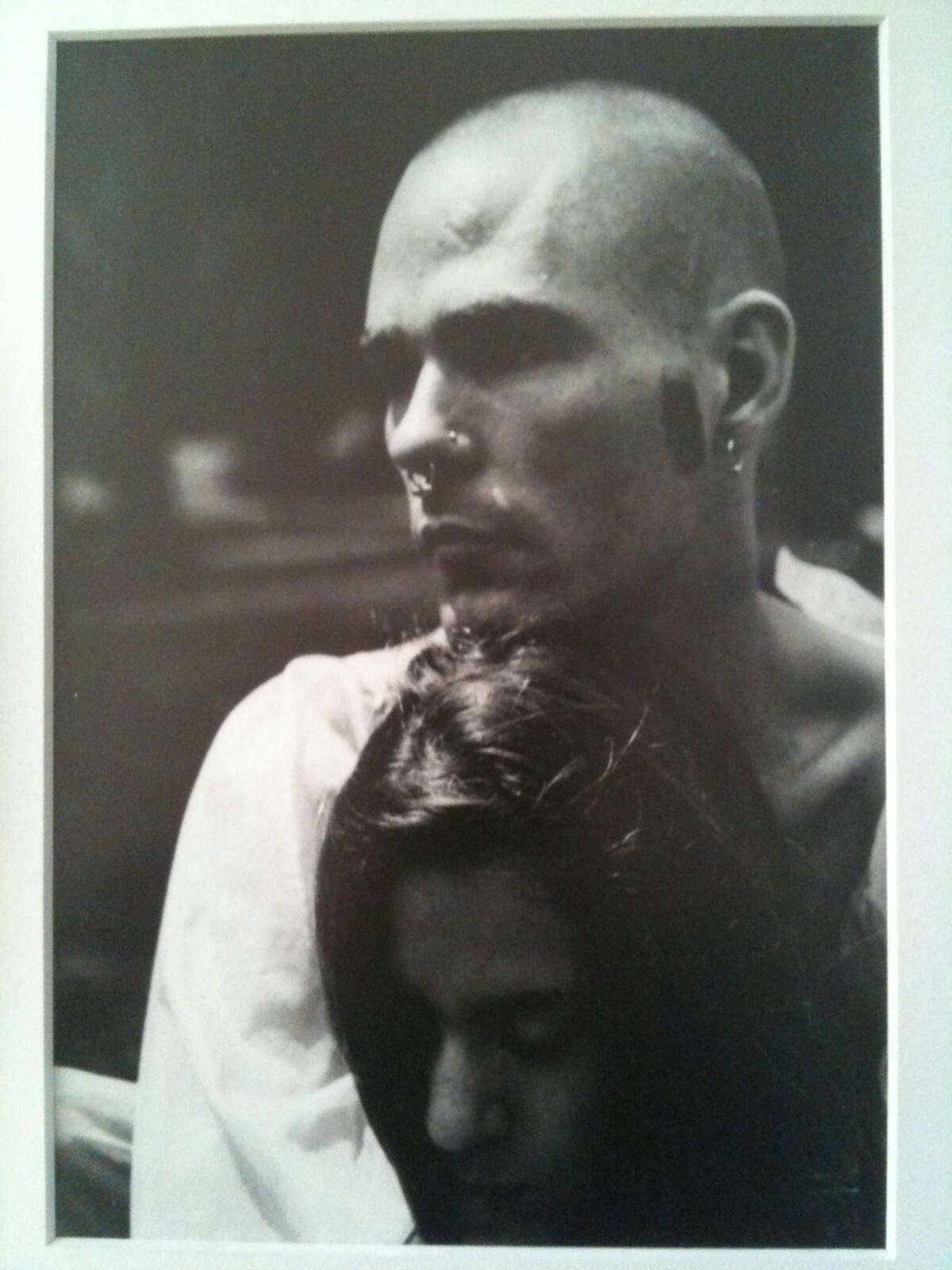

The cross-gender alliances were strong in Los Angeles. At least among the people I was closest to, the people who have the loudest voices in my book. I don’t mean that all of those relationships were sexual, but I might mean that in all of our close relationships, like mine with fellow ACT UP activists Cory and Steven, we experienced an overwhelming intimacy of sharing grief and rage, of caring for each other.

I’m not claiming that there weren’t also profoundly erotic, passionate, fabulously slutty sexual relationships happening in the community, but I am expanding the possibilities of what we mean by queer erotics to include a kind of insistence on vitality, on survival. Intimacy in search of a shape. Sexual and erotic expression and connection was also resistance to the political attempts to render bodies untouchable.

You show your relationship with Cory, a fellow ACT UP organizer, in all its passion and intensity. I actually wondered how it could have existed so openly. But then you reveal that you didn’t tell anyone for 20 years. Talk about the dynamic between secrecy and disclosure.

The fact of our intimacy and our love for each other wasn’t a secret. The explicit sexuality was. There were deep affections between many of the men and many of the women in Queer Nation, and in ACT UP/Los Angeles. We had a significant cohort of HIV-positive cis and trans women, and so the dominant narrative of lesbians selflessly tending to gay men was an oversimplified story that didn’t represent us. There was a sense of all of us fighting for our survival, which meant everyone fighting for everyone else’s bodily agency, including erotic and sexual agency.

I don’t know what Cory would say now about why we kept the sexual aspect of our relationship hidden. There was the fact of our age difference. The fact of the difference in our serostatus. He was HIV-positive, and I was and still am HIV-negative. Why our erotic movement toward and away from each other stood out to me — still stands out to me — is because it felt like we were searching for a release valve for the depth of intimacy that was fostered between us, the terror, the desire for connection. Sex as an act of resisting the feeling of annihilation. And sex as a way to attempt to communicate embodied experience to each other, a bodily intimacy which matched the emotional intimacy. An attempt to keep each other close.

Another thing that distinguishes this book from other AIDS activist memoirs is that it centers around people of color in ACT UP and Queer Nation. Talk about the bonds that sustained you, at the height of the AIDS crisis in Los Angeles, at the time of the Gulf War and the Rodney King verdict.

Everything is always unfolding simultaneously. Maybe because of the demographics of Los Angeles, in my experience the political left had always been coalitional — in union movements, antiwar struggles, and fights for bodily agency and autonomy. Both ACT UP and Queer Nation ran simultaneous projects and campaigns, and I tended to work on committees with the people with whom I felt most aligned and safest. Those happened to be mostly people of color, and some of the white folks who were coming from coalitional, movement-building backgrounds.

We pushed hard in ACT UP and Queer Nation to keep an intersectional frame of reference — though I don’t think we called it that at the time — understanding the connections between prisons; the criminalization of sex work, drug use and HIV-positive bodies; and global struggles against militarization and occupation.

This is not a traditional memoir; it is immersive in a way that follows the patterns of your thoughts, your breath, your memories, your feelings, your inspirations, everything between and beyond, all of this is embedded together. Talk about how you created this form, and what it allows.

In working on this memoir for the many years I did, I felt like I was searching for, and ultimately queering, form. My background in poetry and poetics shows, I think, in my obsessive line editing, and in the associative rather than linear unfolding of narrative.

I knew I needed a present-tense voice that sets up the story from the beginning. The unfolding of the story isn’t the surprise. I’m mining for feeling, for connection and for affective resonance and relationship. The things that surprised me weren’t the facts, but the way I connected and remembered them. That’s always what I’ve been most interested in. The affective toll of grief and resistance and survival.

Working on this project for as long as I did let me reenter in a kind of full-body present tense the intimacies we had all lived through. I wanted every breath to do a particular piece of work: the way patterns of breathing can evoke specific kinds of feelings by the way they activate our nervous systems. And also, I didn’t want to step out of the world we all lived in together and reenter the world without them.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Help us Prepare for Trump’s Day One

Trump is busy getting ready for Day One of his presidency – but so is Truthout.

Trump has made it no secret that he is planning a demolition-style attack on both specific communities and democracy as a whole, beginning on his first day in office. With over 25 executive orders and directives queued up for January 20, he’s promised to “launch the largest deportation program in American history,” roll back anti-discrimination protections for transgender students, and implement a “drill, drill, drill” approach to ramp up oil and gas extraction.

Organizations like Truthout are also being threatened by legislation like HR 9495, the “nonprofit killer bill” that would allow the Treasury Secretary to declare any nonprofit a “terrorist-supporting organization” and strip its tax-exempt status without due process. Progressive media like Truthout that has courageously focused on reporting on Israel’s genocide in Gaza are in the bill’s crosshairs.

As journalists, we have a responsibility to look at hard realities and communicate them to you. We hope that you, like us, can use this information to prepare for what’s to come.

And if you feel uncertain about what to do in the face of a second Trump administration, we invite you to be an indispensable part of Truthout’s preparations.

In addition to covering the widespread onslaught of draconian policy, we’re shoring up our resources for what might come next for progressive media: bad-faith lawsuits from far-right ghouls, legislation that seeks to strip us of our ability to receive tax-deductible donations, and further throttling of our reach on social media platforms owned by Trump’s sycophants.

We’re preparing right now for Trump’s Day One: building a brave coalition of movement media; reaching out to the activists, academics, and thinkers we trust to shine a light on the inner workings of authoritarianism; and planning to use journalism as a tool to equip movements to protect the people, lands, and principles most vulnerable to Trump’s destruction.

We urgently need your help to prepare. As you know, our December fundraiser is our most important of the year and will determine the scale of work we’ll be able to do in 2025. We’ve set two goals: to raise $140,000 in one-time donations and to add 1469 new monthly donors by midnight on December 31.

Today, we’re asking all of our readers to start a monthly donation or make a one-time donation – as a commitment to stand with us on day one of Trump’s presidency, and every day after that, as we produce journalism that combats authoritarianism, censorship, injustice, and misinformation. You’re an essential part of our future – please join the movement by making a tax-deductible donation today.

If you have the means to make a substantial gift, please dig deep during this critical time!

With gratitude and resolve,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy