Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

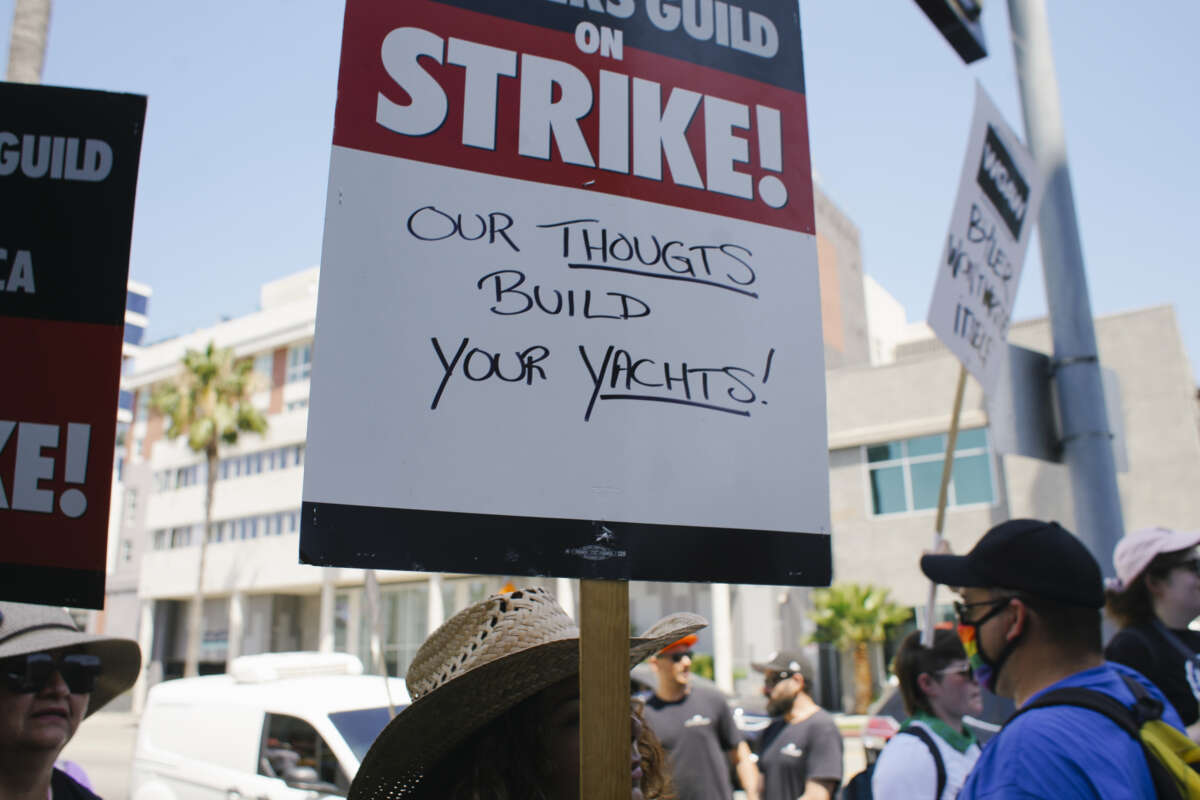

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA) joined the Writers Guild of America (WGA) in striking against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, protesting working conditions, unfair wages and the need for increased residual payments because of the streaming entertainment model. These are all bread-and-butter issues for striking workers, but what makes this strike different is the added concern of the use of artificial intelligence (AI).

The entertainment industry’s expanded use of AI is only beginning. However, writers and actors are raising concerns over the future of AI in the industry, as they set standards to protect the rights of workers. The standards for AI use negotiated by unions will likely set the bar for many other creative industries.

AI has made national news as workers from various sectors (including writers like myself) worry about our place in the economy as technological innovation risks threatening our jobs. But, is it really AI that’s the problem, or is it corporate greed? AI itself doesn’t inherently threaten the livelihood of workers; in theory, it can be used to enhance their work, without replacing them. However, companies’ constant search to maximize profit over people’s well-being has pitted innovation against workers.

The SAG demands that studios commit to not replacing actors with AI-generated content. The union warns that in the near future, studios could pay actors only once for a shoot, and then with AI they could reuse the likeness of actors endlessly for different projects. Background actors are particularly vulnerable to the use of AI, as their contract usually releases the rights for the footage taken by the studio to be used in whatever way the studio sees fit. The WGA flags a similar concern — that AI could be used to replace writers. The union fears that studios can use scripts written over the years by writers as data for AI and lead to AI-generated scripts and pitches.

Both the SAG and WGA unions highlight the fact that studios can use the work already created by actors and writers to train AI, to generate new content. Since studios own the scripts and films made by creatives, under current policies, they could use that content to feed into AI as data sets. Writers and some actors would not get a say or be compensated for this newly generated content even if their work was used as source material. This raises important ethical questions with AI, especially in creative industries: Is AI really “creating” something new? Does the use of pattern recognition and data from source materials count as a unique creation? What is the difference between writers and actors being inspired by past works and AI using source material?

As a creative, I struggle to equate AI-generated capability to human creativity — and I am not alone. When I wrote about 2020 Pride events amid Black Lives Matter protests or confronting catcalling during COVID-19, it was my experience attending and my rich intersectional perspective that illuminated specific issues and connections. AI can’t pull from those lived experiences and would struggle to make meaningful connections on how these movements are linked. But there are some similarities in capabilities, as artists often take inspiration and reference past works, while AI uses past works as data. However, artists of all kinds aren’t just using past works to create new works. Instead, humans are capable of interpreting their own experiences and emotions in creating new forms of art without being exposed to similar work. In contrast, AI must access data sources and interpret the patterns of existing art to “create” something. In short, people can create without source material whereas AI depends on it. It’s important to value the power of human creativity and the work of the artist in developing their craft. That creativity can’t be replicated by AI. And we shouldn’t expect AI to. AI could still be a useful and innovative tool without replacing human creativity.

The SAG and WGA recognize that, which is why they aren’t asking for the banning of AI. Many principal actors can benefit tremendously from leasing out their likenesses for movies. In some steps of the writing process, AI is useful in editing, correcting and fact checking scripts. As an opinion writer, I use AI technology to help correct my work and improve clarity. Yet, I fear that my unique perspective, style and voice can be fed into an AI database without my consent and then used to generate writing for a company to profit off of. But AI isn’t the problem; my fear isn’t directed toward the technology, but how companies will use the technology to exploit my work.

Similarly, the problem that the unions are facing with AI lies in how companies will use creative output and then cut workers out of financial compensation and the creative process. Technological innovation could be an opportunity to improve creative work, raise wages for writers and help streamline their work. Instead, it is corporate greed that pits innovation against workers and creates fear and competition. Consider, for instance, that as many actors struggle to stay afloat earning an average of $26,000 a year, studios are paying top dollar for AI product managers. Studios are moving forward prioritizing AI, rather than the real-life talent that is the heart of the industry.

The unions recognize this issue and focus their concerns on the issues of consent and payment. Writers and actors want to assure that they can consent before their likeness or writing is used by AI to produce content. This is important because current contracts for background actors and many writers allow studios to use their work in whatever way they see fit in the future, which could cover using work for AI. The unions demand that actors and writers have a say if and how their likeness and writing will be used in future projects. Furthermore, actors and writers want compensation for the use of likeness or writing in generating AI content. This can be tricky, as much AI-generated content is still in a legal gray area for the attribution of work used in the data set. Studios and AI scientists will have to decide on a method to identify and compensate the creators in this case. The studios claim that they haven’t moved forward with the expanded use of AI in their productions, but unions are getting in front of the problem as the technological capabilities develop. This is among their many other grievances as they protect the dignity of the creative work of actors and writers.

The emergence of AI in many industries is far from simple, which is why the SAG and WGA unions are demanding that workers have a say. The decisions that are negotiated by these unions and the studios will have a ripple effect across many industries, particularly creative ones. Workers of all sectors must be invited to the table when deciding how AI is integrated into their industry. As actors and writers have shown us in their strikes, they have critical insights into the ethics and impact on livelihood. To move away from the notion that technology is competition, workers must be empowered in creating a collaborative process with AI as it is integrated.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.