Part of the Series

Moyers and Company

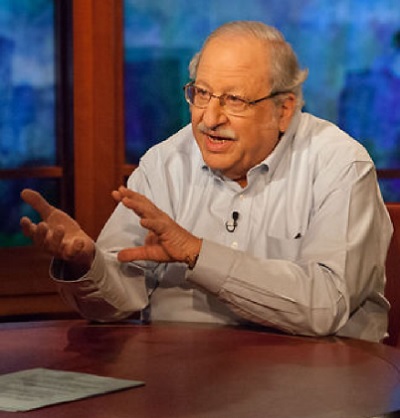

Moyers & Company)” width=”400″ height=”418″ />Activist and organizer Marshall Ganz. (Screen grab via Moyers & Company)Bill’s guest, veteran activist and organizer Marshall Ganz, joins Bill to discuss the power of social movements to effect meaningful social change. A social movement legend who dropped out of Harvard to volunteer during Mississippi’s Freedom Summer of 1964, Ganz then joined forces with Cesar Chavez of the United Farmworkers, protecting workers who picked crops for pennies in California. Ganz also had a pivotal role organizing students and volunteers for Barack Obama’s historic 2008 presidential campaign. Now 70, he’s still organizing across the United States and the Middle East, and back at Harvard, teaching students from around the world about what it takes to beat Goliath.

Moyers & Company)” width=”400″ height=”418″ />Activist and organizer Marshall Ganz. (Screen grab via Moyers & Company)Bill’s guest, veteran activist and organizer Marshall Ganz, joins Bill to discuss the power of social movements to effect meaningful social change. A social movement legend who dropped out of Harvard to volunteer during Mississippi’s Freedom Summer of 1964, Ganz then joined forces with Cesar Chavez of the United Farmworkers, protecting workers who picked crops for pennies in California. Ganz also had a pivotal role organizing students and volunteers for Barack Obama’s historic 2008 presidential campaign. Now 70, he’s still organizing across the United States and the Middle East, and back at Harvard, teaching students from around the world about what it takes to beat Goliath.

One of Ganz’s themes is the crucial role narrative plays in social movements. “I think it’s particularly important because doing the kind of work that movements do requires risk-taking, uncertainty, going up against the odds. And that takes a lot of hope,” Ganz tells Bill. “And so where do you go for hopefulness? Where do you go for courage? You go to those moral resources that are found within narratives and within identity work and within traditions.”

Bill Moyers: At Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, Marshall Ganz teaches the next generation of organizers, students from all over the world. He tells them: when in doubt, just remember the story in the Bible of little David and his slingshot…

Marshall Ganz in class: … what did you take from… the classic story of David and Goliath? How does it begin? How does the whole, when does the action begin?

Male Student in class: Goliath is marching out and repeatedly challenging the Israelites. And no one comes out to challenge him.

Marshall Ganz in class: Right. And so that’s just going on day after day. So then what, when does the action shift?

Male Student in class: When David shows up to bring the food to his brothers and hears this and says, “Why is no one doing anything to respond to this?”

Marshall Ganz in class: In other words, the first thing that happens here is injustice, need to act, commit, and then the action begins. Until that point, nothing is really happening. … When the king says, “Here, take my, take my helmet, take my shield. Take my armor.” What, what’s David do?

FEMale Student in class: He puts it on…

Marshall Ganz in class: Puts them on. See David doesn’t have it all figured out. That’s the point. He’s in action here. He doesn’t have it all figured out. The king says, “Well, you going to fight power? Here, you need weaponry to fight power.” David actually takes them, he puts them on, and then what happens?

He can’t move. They’re too heavy, literally. He can’t move. That’s when he has his moment of insight and he looks down at his feet and he sees these five stones there. And says wait a second. I’m not a soldier. I’m a shepherd. And that’s, Tim, when he says, “As a shepherd, I knew how to protect my flock from wolf and the bear. And it wasn’t with a sword, and it wasn’t with a shield. It was with a stone and a sling.” Maybe Goliath’s just another wolf. Just another bear. What’s Goliath’s reaction? Ho. Ho. Ho. Am I a dog? You send a boy with a stick. And in the middle of the third “ho” a stone in the forehead and into Goliath. And not a story about non-violence…

Bill Moyers: Smiting Goliath might as well be Marshall Ganz’s job description. It began in Mississippi’s Freedom Summer of 1964 when his fury against injustice pulled him out of Harvard and into the struggle for civil rights. From there, he signed on with the legendary Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers and for 16 years, struggled to unionize the men and women in the fields of California who toiled endless hours and mounting days, picking crops for next to nothing.

Three decades after Marshall Ganz had dropped out of Harvard, he went back to finish his degree and earn a doctorate. A few years later, he was asked to become the architect behind the Obama campaign’s skillful organizing of students and volunteers.

Today, Marshall Ganz is a founder of the Leading Change Network, a global community of organizers, educators and researchers mobilizing for democracy. You’ll find more of his experience and philosophy in this book: Why David Sometimes Wins.

Bill Moyers: Marshall Ganz. It’s good to meet you.

Marshall Ganz: It’s good to meet you, Bill.

Bill Moyers: Stories have been a powerful part of your life. Where did that come from? Why stories?

Marshall Ganz: First of all, I grew up in stories. My fathers a rabbi. And I grew up with the Exodus story as a child. And I was always puzzled by the fact that, you know, they said that at a certain point you were slaves in Egypt. I’d never been a slave or been to Egypt, they’d say to the children. And, but then I came to realize that what it meant was the story really wasn’t the property of one people, time, or place.

And then out to the farm workers. And we’re in the religious narrative. I mean, one of my first assignments in the farmworkers was to organize a march from Delano to Sacramento. But it wasn’t a march. It was a peregrinación. It was a pilgrimage. It was at Lent. It reached Sacramento on Easter Sunday.

It was like an enactment of the redemptive narrative of Easter. But it was built into the movement that we were building. So in my experience in organizing, it was also all within narrative. And so we kind of knew that narrative stories mattered. And they mattered to the heart. And they weren’t the whole story. The whole story, so to speak. The strategy mattered, structure mattered, but narrative mattered, the motivation, the courage.

Bill Moyers: Until I read your book about Chavez and the strikers, I didn’t know how much of their own efforts revolved around stories. But then when I read your book, I realized how the stories that they told, the stories that they inherited, added up to a story that they wanted to leave for their children.

Marshall Ganz: Sure. But I mean, that’s one of the things that distinguishes movements from, like, interest groups. Movements have narratives. They tell stories, because they are, they are not just about rearranging economics and politics. They also rearrange meaning. And they’re not just about redistributing the goods. They’re about figuring out what is good.

So they have this cultural piece of work that movements are doing, along with the economic and the political. Not in lieu of it. And I think it’s particularly important, because doing that kind of work that movements do requires risk-taking, uncertainty, going up against the odds. And that takes a lot of hope. And so where do you go for hopefulness? Where do you go for courage? Where do you go? You go to those moral resources that are found within narratives and within identity work and within all faith traditions, cultural traditions.

Bill Moyers: You know, Campbell told me that that was the great appeal to him of Carl Jung. That Jung wrapped his psychology into the stories of what had actually happened in his life and, and in the lives of the people sitting in front of him. And if he could get somebody into a story, he knew that person would discover who he was more likely than if he dealt with just abstract ideas.

Marshall Ganz: Boy, it is so true. It’s the particular. See, we often think, we associate understanding with abstraction. It’s just the opposite.

Bill Moyers: That’s right.

Marshall Ganz: The particular then becomes the portal on the transcendent, because it’s through the particular experience that I’m able then to communicate the emotional content of the value that is moving me.

You know, my father was a chaplain in the American Army. And we lived in Germany after the war for three years. You know, my fifth birthday party was what, he worked a lot with what were called DPs.

Bill Moyers: Displaced Persons.

Marshall Ganz: Well, my fifth birthday party was in a camp of, a DP camp of all children. And my mother thought that I should give presents rather than get them. Well, I didn’t quite get that. And I actually thought it was kind of cool that there were no parents, until later I realized why there were no parents. And so it was, it was sort of a moment and then a deeper understanding of that moment later that sort of was a kind of sobering experience and helped me understand the emotional work that’s there that stories do.

Bill Moyers: How so?

Marshall Ganz: It helped me understand that dealing with, dealing with fear is probably the central moral question we have to deal with. By moral, I mean, if you think, if you think of moral questions as not being about principles, but more what Jung called “moral sentiment.”

In other words, how do I live with empathy as opposed to alienation? How do I live with a sense of my own value as opposed to a feeling of deficiency? How do I live in a spirit of hope instead of fear?

Bill Moyers: How to be in the world, right?

Marshall Ganz: How to be in the world and capable of moral engagement with other human beings is sort of how I think of it.

Maimonides, the 12th century Jewish philosopher defined hope as, said, “Belief in the plausibility of the possible as opposed to the necessity of the probable.” Now let me say that again. That to be a realist is to recognize that the world is not a domain in which the probable always happens. I mean, Goliath is more likely to win. But, you know what, sometimes David does, you know?

Bill Moyers: Was there a time you had to do that, when you had to suspend disbelief and see that the inevitable was not a necessity, that it was a probability?

Marshall Ganz: Boy, I you know, well, first of all thinking I can get into Harvard in the first place from Bakersfield, leaving Harvard to go work in Mississippi is…

Bill Moyers: You left before you finished your studies?

Marshall Ganz: Yeah, I had a year to go. But see, when I left, it was to just go for the summer project. But I found a calling there.

Interviewer: Marshall, what are your motives for going down to Mississippi this summer?

Marshall Ganz, 1964: Reading the papers last year, talking with people, and hearing about what was happening in Mississippi and the South, shooting of Medgar Evans and other events like that generates such a feeling of outrage and injustice that you feel you must act.

Marshall Ganz: I found this thing called organizing, which I had never really understood or heard of. And it wasn’t about charity. It wasn’t about, you know, helping. It was about it was about justice. It was about working with other people in a way that respected and enhanced their agency and my own at the same time.

Bill Moyers: How did you learn that?

Marshall Ganz: Through being part of it.

Marshall Ganz: Our initial project, so we were trying to claim voting rights because African Americans of course, didn’t have the right to vote in, any practical right to vote in Mississippi, Alabama, much of Georgia, and so forth, in those states, at that time.

The work was to build a parallel organization called the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party that was because the regular Democratic Party excluded Blacks.

So our idea was we were going to build a parallel one, choose a delegation, go to the Atlantic City Democratic Convention, 1964, challenge the racist Democrats, and replace them with our Democrats. And that was going to be a blow for the civil rights movement.

So the work was going to people’s houses, Black people, talking with them, registering the Freedom Democratic Party, have a house meeting, come to a caucus, get elected.

Working with people to find courage, to find solidarity, to find a sense of hopefulness, to stand up to pretty scary stuff. I mean, you know, three of our group were killed before we even left Oxford, Ohio. That was Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner. And so it was, I’ve often thought about that book by Paul Tillich, Love, Power, and Justice.

Bill Moyers: Love, Power, and Justice.

Marshall Ganz: And where he argues that power without love can never be just, but similarly love that doesn’t take power seriously can never achieve justice. And that was, I think, what I learned.

Bill Moyers: You’ve said that when you tell a story, the story becomes three stories.

Marshall Ganz: Yes. Well, when we do public, so public narrative, is like a leadership skill of moving people to public action. So there’s a story of self, which is using narrative to communicate why I’ve been called. So I tell stories that can communicate the values that move me. A story of us is using narrative to create a sense of the values we share as a community. And then the story of now is do they experience the challenge to those values that requires action now? So sort of three pieces.

Bill Moyers: So that’s what Martin Luther King meant when he talked about the urgency of now at Riverside Church?

Marshall Ganz: That’s exactly right. And you’ll see in that talk his calling and then he reminds us of what we’re called to as African Americans, as White Americans, and as Americans.

Martin Luther King Jr: “We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history, that is such a thing as being too late… And if we will only make the right choice, we will be able to transform this pending cosmic elegy into a creative psalm of peace. If we will make the right choice, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our world into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. If we will but make the right choice, we will be able to speed up the day, all over America and all over the world, when “justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Marshall Ganz: It’s so amazing the way he’s able to speak the, the Christian language, but in a way that’s inclusive and not exclusive. It’s really extraordinary. It’s extraordinary. And then and then because we share those values, guess what, folks, we face the fierce urgency of a now that requires action. That’s what public narrative is.

Bill Moyers: Is it true that the slogan for Cesar Chavez and his farm workers was “si se puede”?

Marshall Ganz: Si se puede, yeah.

Bill Moyers: Which translated literally into Obama’s…

Marshall Ganz: “Yes, we can.” Oh, you betcha.

Bill Moyers: Is that right?

Marshall Ganz: Well, “si se puede” came in Arizona, 1972 Arizona had a governor Jack Williams that passed a law that denied farm workers the right to organize, boycott. I mean, it was a terrible law. And so we had to figure out were we going to challenge it or not?

So we all went to Arizona to challenge it. We got there. And went out talking to people. And Dolores Huerta actually came back. We were meeting in a hotel/motel room. She said, “I’ve been talking to all these everywhere. And everywhere I go, people say, ‘no se puede,’ ‘no se puede.'” She goes, “Ah, you can’t do it. You can’t do it, you know? It’s just too, you know? And we got to, we got to answer that. We got to say, ‘si se puede.'” And so that became the slogan in that campaign was “si se puede.” Yes, it can be done. And that then became a farm worker movement slogan. “Si se puede.” So in New Hampshire, when Obama lost that night, and there was a lot of that talk going on around.

Barack Obama: Generations of Americans have responded with a simple creed that sums of the spirit of a people.

Marshall Ganz: Then comes out, “Yes, we can.” Well, that’s “si se puede.”

Barack Obama: Yes we can. Yes we can.

Marshall Ganz: That was a great moment. That was what sort of raised such hopes about his presidency.

Bill Moyers: Did people count too much on his charisma and didn’t assess his inexperience sufficiently.

Marshall Ganz: Oh, in retrospect, you know, probably so, you know? But I don’t know, I think there’s plenty of responsibility to go around. I mean, I think there was too much readiness to just leave it up to Obama. And I think that those of us who wanted to do more about economic justice and immigration and climate change needed to do more.

We had to be contentious. That’s how it works. It’s like this idea that contentiousness is somehow alien to democracy and that consensus is somehow what democracy is about and that polarization is bad, paralysis is bad. But, you know, it’s like Saul Alinsky says… Organizers have to be well-integrated schizoids, because you have to polarize to mobilize and depolarize to settle. But without polarizing you’re never going to mobilize anything. And yeah, then there’s a time to negotiate. And I think we’re really screwed up on that right now…

Bill Moyers: It’s always been struggle and conflict and winners and losers that move us forward or backwards.

Marshall Ganz: That’s the heart of democracy, democracy is a system of contention. I mean, of constructive contention when it works.

Marshall Ganz in class: What did the farmworkers want? You remember in the farmworker story? Those that read that one? You remember in this context, in this moment what they wanted?

Male Student in class: Is it recognition for UFW?

Marshall Ganz in class: Yeah, it was recognition and it wound up being recognition from a particular employer, Schenley Industries, a big liquor company in Vallejo. And union recognition means a contract signed between the workers and the unions specifying wages, hours, working conditions and all the rest. Very, very concrete objective. Right? But that was, like, the focus of their efforts so that they could then move toward the bigger goals of broader justice and all the rest of it.

And so the whole point about outcomes is specifying them clearly enough that you can actually focus in and commit to making it happen or not. And, and I think a lot of project are struggling with that right now. It’s how to specify the place between, you know, justice out there, goodness in the world and, like, my next meeting.

Bill Moyers: Suppose one of those students said to you, “Professor Ganz, I know that the farm workers were out-financed and outmanned. And I know they were opposed by business owners and other labor leaders spurned them. Yet, you say that they worked out a successful, grassroots strategy to organize illiterate grape pickers. Is there any lesson in that?

Marshall Ganz: The lesson would be to look at how it was they figured out how to do it. See, it’s sort of like you don’t copy that. But you sort of look at the depth of motivation they brought to it, the creativity. How did they figure out their strategy? How did they understand power? What did they understand about it? How did they continue to renew their spirit that they were able to keep moving forward.

Bill Moyers: How did they?

Marshall Ganz: Well, there was a lot of this heart work, a lot of the narrative, the storytelling, a lot of the celebratory, a lot of the nurturing of the heart. I mean, you know, it took us five years to run a grape boycott. And we had to reinvent that thing every year. And every year, you’re going back in and saying, “Okay, we got to start again.” But you find in each other, in the solidarity, in the myths if you wish that— that feed you the capacity to keep going.

Bill Moyers: I remember what you wrote once that you had learned in Mississippi during the summer of 1964. You said all the inequalities between Blacks and Whites were driven by a deeper inequality, the inequality of power. That seems to me, the fundamental reality of American life today.

Marshall Ganz: Yeah, I think the political inequality and the economic inequality and a kind of cultural inequality that sort of all reinforce one another is an enormous problem, obviously. I mean, that’s sort of what we’re trying to deal with. And so the question and in some ways, you could sort of think that liberal democracy is based on a deal that inequality and economic resources can be balanced by equality in political resources. In other words, that equal voice can somehow balance unequal wealth. Well we’re sort of way beyond that. And…

Bill Moyers: One man, one vote, one person, one vote has been, has been overwhelmed by $100,000 and a million dollars.

Marshall Ganz: And it’s not even just the money. If you live in a swing state, your vote counts so much more than if you live in New York or Illinois or California, when it comes to electing a president. If you live in a swing district, when it comes to electing a member of Congress, your vote counts. If you live in a district that’s been gerrymandered so it’s all Democrats or all Republicans, your vote does not count. So when you really look at whose votes count, it’s a very, very small proportion.

So we have some deep structural flaws that go all the way back to the beginning that aren’t, they don’t, it’s not about us as a people or our culture, our beliefs. We’re operating within in a set of political institutions that distort and actually warp our capacity to express our beliefs. Maybe what we really need is an equal voice amendment to guarantee that each vote actually had equal weight. That’d be pretty radical. And if we actually designed a system that did that, now, you know, would we get something like that tomorrow? No, probably not. But, but I guess my point is that, that there are a lot of sources of energy and change in a country, not to mention the world. A lot of it is generationally driven. It’s in places that may be unexpected.

Bill Moyers: Let me come closer to where you and I are today, Occupy Wall Street did pull economic inequality out of the closet and put it at the breakfast table, the lunch table, the dinner table, and the political roundtables on Sunday. But it didn’t hang around to fight for it. What happened?

Marshall Ganz: Well, I think, I think Occupy made a great contribution in that it did what you just said. It, it took economic inequality, economic justice and made it legitimate. But they got stuck. I mean, they got stuck on a tactic, without a strategy that went beyond a tactic.

And, you know, one tactic doesn’t build a movement. It takes, it takes venues in which people can strategize about how to move the ball forward. You know, I mentioned at the beginning sort of these three elements of story, strategy, and structure that you sort of need to build a movement, an organization.

You got to have your, the narrative is the “why” we’re doing it. And then the strategy is how we’re doing it, not just one tactic, but how, what’s our theory of change. What’s our theory of how we’re going to use our resources to influence those sources of power. And then how are we, what’s our structure through which we’re figuring all this stuff out and working at it? And so they had problems there. You know, people confuse structure with oppression. And Jo Freeman wrote a great piece, this…

Bill Moyers: The feminist?

Marshall Ganz: The feminist sociologist, called “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” and I have all my students read it, where she argues, you think structurelessness, you’re kidding yourself. Any time a group of people get together, they’re going to create a structure. The difference is whether it’s visible or invisible, whether it’s accountable or not, and whether it’s open and above board and, or whether it’s all factionalized and personalistic. And so you choose what you want.And I think it’s really honest. And so the rejection of structure is a sort of rejection of taking responsibility for self-governance.

Bill Moyers: So you talk about the power of story and for the last 40 years, the story of the free market has been the triumphant story in American culture.

Marshall Ganz: It really is, you know? And it’s powerful, because it has a moral dimension and it has a political dimension and it has an economic dimension. It’s sort of like that the market means we’re all free to make our own choices, so isn’t that great, because we want to be free. And it’s all about choices.

And politically, well it’s all based on people making their choices. And so that’s democratic. And economically, well, we all know it’s efficient, right, because that’s how markets work. It’s, and the problem is every one of those claims is fundamentally flawed and fundamentally an act of faith. I mean, Harvey Cox wrote this thing about the market is God. And…but the big question is where’s the missing alternative counter to that? And I think that is an enormous intellectual challenge for our time right now. Where’s that alternative?

Bill Moyers: We need a new story?

Marshall Ganz: We need a new story. But it’s also a new way of describing our economic challenges and our political challenges that emphasizes not this idea of what each individual competes with, each other individual as the answer, but the ways in which we cooperate and collaborate with one another as the answer.

You know, Albert Hirschman, the development economist wrote this book a number of years ago, I’m sure you know about it, “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.” And sort of the idea was, okay, so you got an institution. And it’s screwing up. And so one way to fix it is to exercise voice. The other way is you can exit. The market solutions are all exit solutions.

Bill Moyers: Explain that to me.

Marshall Ganz: Well, so you don’t like the way the schools work, exit, make your own over here. And that way you exercise choice. You don’t like the way public health works, exit, over here, make your own. Now the only problem is you can only exit and make your own if you got the money to do it. And so the result is that you create these parallel systems of elite systems that are, you know, that fragment the whole.

The public gets poorer and poorer and poorer, and you create all these little isolated golden ghettos all around of privilege. And the focus is on how do we find market solutions, market solutions, market… when we should but saying, how do we find more effective ways to exercise voice? How can we have more, more effective public deliberation? How can we bring more people into the process? How can we create the venues where people can actually learn and deliberate with one another?

Bill Moyers: Can you take this one step further or beyond government over to the leadership of other institutions, business leaders, educational leaders? I mean, how do we write a narrative that includes them in this new story of collaboration, cooperation?

Marshall Ganz: You know Karl Polanyi’s book, “The Great Transformation,” written in 1941, sort of nailed it when he said, if you have a good that can, where price captures value, you can marketize it. And where price does not capture value you cannot marketize it.

And he was talking about labor and land when he was writing in 1941. And he was trying to explain the, the problem of the open market system after World War I that had wiped out all sorts of social structures that cleared the way for the rise of fascism in Europe. I mean, this is the context he was writing in. He was saying, “So the open market system was allowed to be a solvent that ground everything down.”

Because it doesn’t respect values other than price values. Now how do you put a price on education, really? How do you put a price on health, really? How do you put a price on art, really? Now when we price these things, we undermine their value. And so that’s why we need churches. That’s why we need schools whose value isn’t based on pricing, it’s based on a different set of understanding and the resources that it generate doesn’t depend on pricing. So I don’t know. There’s potentials out there. But I think somehow we need to get this into the, we need to get into this debate. We need to get into this argument and have it be about something really substantive. And not get drawn into these, “Oh, we’re too polarized” or something. We need to be more polarized, but polarized around the right things.

Bill Moyers: Is there any kind of organizing like that going on?

Marshall Ganz: There’s a lot of organizing going. I’m privileged to get to see it, because I work with young people. Within the immigrant world, the dreamers have done some great stuff. I mean, they do the organizing, the house meetings, the one on ones, all that good old organizing stuff. You know, the crew of young organizers came out of the Dean campaign in 2003 in…

Bill Moyers: Howard Dean?

Marshall Ganz: Yeah, 2003-04, and that crowd that have, you know, percolated through Obama and all that in a variety of different ways. But they’ve brought sound organizing techniques into electoral politics in a way that had disappeared. It had all been marketing. It was all marketing. And not that marketing’s not there now in a big way.

But the confusion between marketing and movement building is really a big one. And I think that’s one of the things the environmental groups really, really missed the boat on. I think they thought that they could market their way to legislation. What I mean is that through polling and advertising, they could make what, the changes they wanted palatable to enough of the people that they could, in that way, create enough of a ground that they would get the legislation.

That’s a marketing proposition. Movement building is you know that you don’t have a majority. What you got to do is build enough of a constituency that you can develop the power you need in order to achieve what you want. And so what you’re doing is engaging people, who engage other people, who engage other people. And you build a movement that way.

Bill Moyers: Looking back on your life, is there a core to it? Is there a common denominator?

Marshall Ganz: There were three questions posed by a 1st century Jerusalem scholar Rabbi Hillel, when asked “How do we, how do we understand what we are to do in the world?” And he responded with three questions. The first one’s to ask yourself, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” It’s not a selfish question, but it is a self-regarding question. Sort of saying, “Ask yourself what you’re about, what you value, what you have to contribute, what…” But then the second question is, “If I am for myself alone, what am I?” But it, which is, it’s to even be a who and not a what is to recognize that we are in the world in relationship with others and that our capacity to realize our own objectives is inextricably wrapped up with the capacity of others to realize theirs.

And finally, “If not now, when?” The time for action is always now, because it’s often only through action that we can learn what we need to learn in order to be able to act effectively in the ways that we intend. And the fact that they’re questions is also really important to me, because it suggests that this work, this work of organizing, leadership is not about knowing, it’s about learning.

And it’s about asking and it’s about understanding that it is about dealing with the uncertain. It is about probing the unknown. It’s not about control. It’s about, it’s about learning through purposeful experience. And so that’s kind of, I think, what I’ve tried to, as I look back, what I’ve tried to learn, to teach, to do, to practice is how to be that kind of a learner and teacher.

Bill Moyers: Marshall Ganz, I look forward to the next chapter of the story. Thank you for sharing your time and ideas with me.

Marshall Ganz: Thank you, Bill. Thank you very much.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $33,000 in the next 2 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.