Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

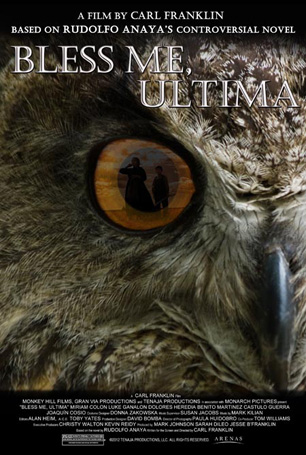

Brown faces along with the magic of northern New Mexico’s landscapes and Indo-Hispano culture in new movie, Bless Me, Ultima, charm Roberto Rodriguez.

First a confession: I was not a Chicano Studies major when I attended UCLA back in the day. Probably for that reason, I have never read Bless Me, Ultima, cover to cover. That’s probably an unpardonable sin, akin to me never having donned a Zoot Suit.

But let’s talk about the new movie, set during World War II in northern New Mexico. Yet, for me, the context is always Arizona.

Read more articles by Roberto Cintli Rodriguez and other authors in the Public Intellectual Project, here.

Bless Me, Ultima is one of the books that was at the core of Tucson’s controversial Raza Studies curriculum. It had been previously banned around the country, but the Tucson Unified School District put it on the map in 2010 by shutting down the program, essentially banning all books and other materials (the Aztec Calendar) associated with it. All this was precipitated because then-state superintendent of schools, Tom Horne, decided that Raza Studies were “outside of Western Civilization.”

That said, I would recommend the movie to any and all past, present and future censors, starting with Mr. Horne, his successor, John Huppenthal, current Tucson superintendent, John Pedicone, all the TUSD school board members and all the state legislators (nationwide) who have conspired to destroy Raza Studies.

To them and to the world, I would say: Bless Me, Ultima is Raza Studies!

From the opening scene, it is magical. More than magical is the beauty of New Mexico, whose reality is virtually unknown to urban types (like myself), who grew up knowing little of the land, the mountains, the waters and the open skies.

Ultima is a curandera, an Indigenous healer, who moves in with a family in a village in northern New Mexico, where everyone knows each other but where feuds stretch far back, and where violence is no stranger.

In the movie, Ultima takes 7-year-old Antonio under her wing, teaching him about life, about medicine, about the natural world, but most of all, about the nature of human beings.

Without giving the story and ending away, Bless Me, Ultima indeed is about pride and prejudice. It is about faith and beliefs in a “modern world.” Its power is that it is seen through the eyes of a 7-year-old, a boy who is destined to become a priest.

Ultima is recognizable – a woman whom people both respect, but also fear, and as the movie shows, a woman who is shunned, even after she heals. Unstated is that this story takes place among what people refer to as an Indo-Hispano village.

The fact that the book and movie touch upon the subject of curanderas is what roils conservatives. Just as in the movie, Ultima is accused of being a witch who practices witchcraft. Many of the village people react to her, akin to the way they’ve been taught to react for 500 years.

Beyond watching the movie (and reading the book), I would recommend two related books: Women and Knowledge in Mesoamerica: From East L.A. to Anahuac (2011) by Paloma Martinez-Cruz and Red Medicine (2012), by Patrisia Gonzales, both from the University of Arizona Press.

Both deal with the topic of woman healers and their knowledge and medicines that survive the so-called conquest, or European invasion. It is living knowledge, knowledge that cannot be destroyed, despite a 500-year effort.

The magic of Bless Me, Ultima is beyond its content; it is, after 41 years, the ability to see Rodolfo Anaya’s classic work on the big screen. Truly, to see brown faces throughout the whole movie, not simply in support roles or as extras – was part of the magic.

In effect, Bless Me, Ultima was one of the first fruits of the Chicano/Chicana literary renaissance. It made me and makes me wonder when we will be seeing a few more classics, a product of the Flor y Canto (translation: flower and song) Movement of the 1960s-1970s, also referred to as “In Xochitl In Cuicatl.” There are hundreds of stories ready to be told.

To author Rudy Anaya: Gracias-Thanks-Tlazocamati. For more info, go to: blessmeultima.com.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Our fundraising campaign is over, but we fell a bit short and still need your help. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.