Part of the Series

Despair and Disparity: The Uneven Burdens of COVID-19

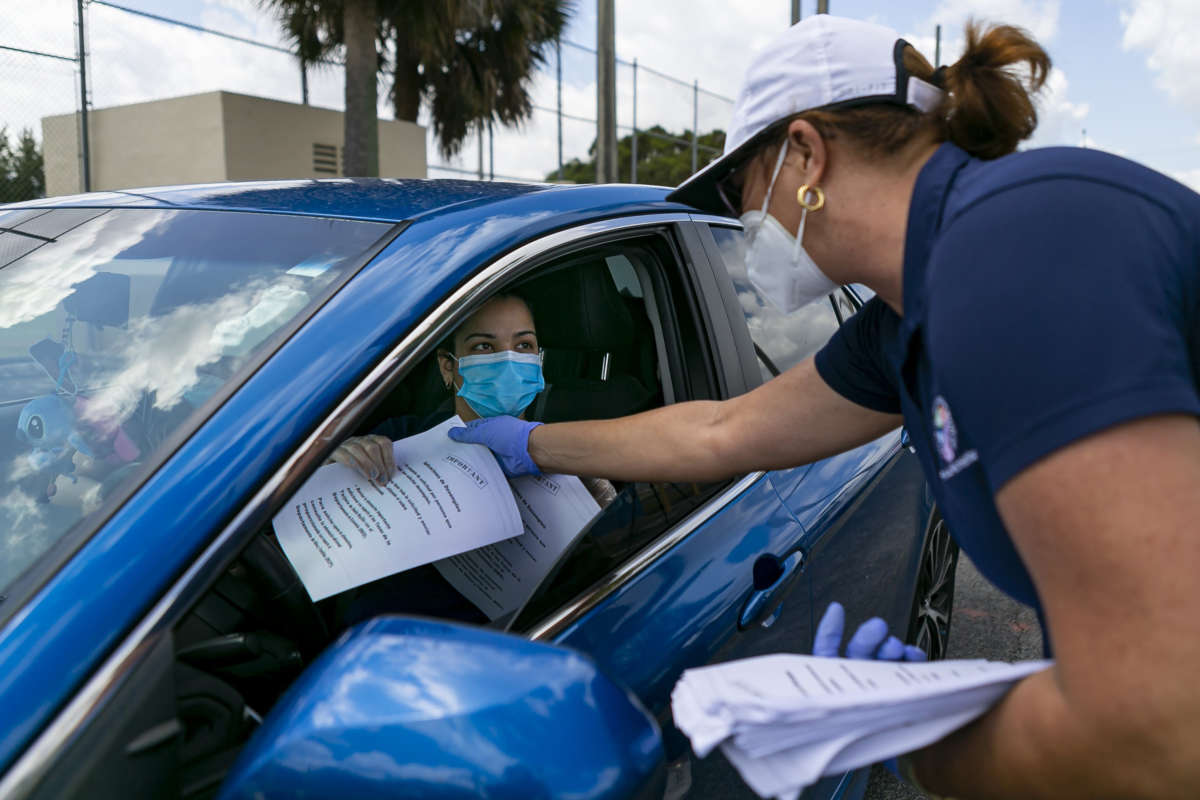

As the COVID-19 pandemic creeps into the summer, over 38.5 million U.S. workers are now jobless. While an unforeseen era of social distancing takes hold, consumer purchasing has slowed to a crawl, labor markets face shortages and supply chains are interrupted. Unprecedented economic uncertainty for the world’s population — the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the Great Depression — has brought economies and incomes to a standstill.

With U.S. lawmakers providing the largest handout to corporate America in history, workers have seen little relief and are struggling to keep afloat as income is ceased, bills pile up and unemployment relief is slowed. The most profitable multinational corporations, Wall Street speculators and insurance oligopolies have received trillions, while only some U.S. workers have seen a one-time payment of $1,200. Without income or guarantees from the government, consumer demand, supply chains and working people are on the brink.

As economies teeter and workers struggle, world governments are looking to Universal Basic Income (UBI) to solve their economic meltdowns while keeping in place social distancing and other health precautions. To ward off a total economic and health disaster, a permanent UBI — coupled with an expanded social safety net — would ease precarity for workers during the COVID crisis and help remedy existing disparities that have intensified due to the pandemic.

With U.S. politicians seeking bipartisan business-friendly responses, the debate on protecting the income of ordinary people and UBI has made waves abroad. Nations and leaders across the globe are considering guaranteed income, while results from a basic income experiment in Finland have shown a glimpse into basic income’s potential of alleviating economic stressors for workers. In the wake of the pandemic’s devastating effects on the interconnected globalized economy, Spain has passed a permanent income program to account for massive layoffs and a consumer demand collapse.

Minimum Income Abroad, a Step Toward UBI

In April 2020, under the coalition government led by the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, Spain passed a permanent minimum income program — a policy of guaranteed income for qualified low-income workers and families. The minimum income program adopted by the Spanish was pushed by the PSOE-led coalition and Sánchez in response to the economic fallout generated by COVID-19. According to the Spanish publication La Vanguardia, under the new program, low-income families with two children could receive €1,000 ($1,092), while individuals who live in poverty could see up to €500 ($546) monthly.

At a press conference on May 23, Sánchez stated, “It will cost around €3 billion ($3.24 billion) per year, will help four out of five people in severe poverty and benefit close to 850,000 households, half of which include children.” The program is estimated to benefit 2.5 million Spanish citizens or about a little over five percent of the population. According to Spanish officials, the income program will be limited to targeted low-income families and individuals, with the benefit adjusted based on income level and factors like number of children per family and mono-parent households receiving more assistance. The program will allow beneficiaries to retain other benefits and have a guaranteed income regardless of employment status. Spain’s ministers have signaled a move toward a permanent and universal income model in the future. As the initiative moves forward, more details on the program’s implementation are expected to become available.

At the moment, the income proposal is not universal, although PSOE and other government officials have stated that over time the nation will move to a universal and unconditional model, in which every Spaniard receives guaranteed income with no strings attached. Social Security Minister José Luis Escrivá told Spanish outlet La Sexta that UBI will come to Spain “as soon as possible.”

Spain stands as the second nation to move toward a form of an income guarantee on a national level, joining Iran which implemented a UBI program between 2010 and 2011. Although Iran was the first to adopt an income program at a national level, it ended up facing backlash and was reined in after some argued that it disincentivized work, a notion which was later dispelled. When first introduced, the program was widely rejected by the public as it replaced large state subsidies to energy and grain, yet overtime support for the program grew as Iranians saw a 29 percent median household income increase. The gain equated to a $1.50 increase per day for households, which in the U.S. would equate roughly to an extra $16,389 annually. The Spaniards and Iranians aren’t alone in their support for UBI. Portuguese and Italian ministers have echoed calls to join Spain in protecting workers’ income during the pandemic, while many leaders in other countries, including the Netherlands, Australia, Japan, New Zealand and Singapore, debate the subject.

As the economic fallout from the COVID-19 quandary continues to create uncertainty, support for UBI is reaching high levels in Europe. A poll conducted in March 2020 by Oxford University researchers showed that 71 percent of Europeans support the adoption of a basic income program. Before the shockwaves of the pandemic set in, there was similarly broad support for basic income in Europe, reaching 64 percent in March 2017.

High levels of European and national support, along with longtime mainstream enthusiasm, led the Finnish government to run an experimental basic income program from 2017 to 2018. The study ran for two years, during which the Finnish government allocated no-strings-attached monthly cash payments to 2,000 unemployed workers. Selected participants received a monthly payment of €560 (fluctuating between $590 and $635 during the two years the study was conducted).

While the program wasn’t ultimately adopted by Finland — due to political dogfights, bureaucratic budget controls and social constraints — the study found that UBI had a positive impact on improving worker fulfillment and happiness and also had minimal impact on employment status. In other words, data wasn’t statistically significant to conclude if employment was disincentivized or incentivized (although employment prospects did increase for some individuals in year two of the trial). The effect on employment is significant considering UBI detractors — mostly reserved to conservative liberals and the right who embrace the “power of work” — argue that a basic income will disincentivize workers from seeking employment, a conclusion which economists studying Iran’s UBI program and others have rejected.

Basic Income, Worker Protections and Universal Programs

UBI has great potential in nations with comprehensive benefits programs and solid social infrastructure. Although nations around the world have seen decades of austerity measures applied over the neoliberal era, strong social safety nets have worked well to promote solidarity, better fulfillment of the working class and act as a stopgap to mend the failures of a skewed economic system.

Like many world allies, the U.S. has seen its fair share of austerity. Unlike the U.S., however, most Western peer nations created stronger social safety net systems, based on universality, and made substantial investments in health, education, pensions and consumer protections. Even with decades of austerity, many nations around the world have eclipsed the U.S in providing universal and comprehensive benefits to workers. What little remains of the American benefits and social safety net system has been deprived of resources, means-tested or sacrificed to privatization at the altar of budgetary deficits and bipartisan, neoliberal cost-cutting reforms.

Some proponents of UBI — mostly reserved to capitalist libertarians and the upper echelon of the Silicon Valley tech crowd — argue in favor of a UBI program as a means of gutting “entitlement spending” and throwing poor people “off” of welfare. Under the guise of creating a more efficient bureaucracy by cutting off lifesaving social programs, the right’s reasoning for basic income will only exacerbate poverty and leave working people worse off. A UBI will only be successful in its intent of alleviating financial hardship and creating more efficient social programs when its coupled with a robust safety net modeled on an unconditional, universal framework.

A depleted safety net would mean a UBI alone would do little to provide economic relief for workers. Without universal programs, hardy workforce protections (like a federal jobs guarantee or trade unionist policies) and the little that remains of social safety nets, any gain UBI provides will be offset by the high cost of other essential goods and services, like raises in rent, and health and living costs. A form of basic income coupled with a strong national health care system like the National Health Service in the U.K., Denmark’s pension system or Berlin’s rent controls, poverty and financial struggle will be better addressed than a UBI with austerity or elimination of the social safety net.

Universal Basic Income Before and After COVID

In her 2007 book, Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein asserts that in times of disaster, capitalism and its political systems have a tendency to naturally apply austerity. Klein now argues that the opposite can be true, that working-class-centered policies can be achieved in times of crisis, as a world debate sparks and Spain moves toward UBI. The likelihood of U.S. political elites adopting any sort of income program or expansion of the social safety net seems far from conceivable, yet given that the pandemic has shown the fragility of the U.S. and world economic systems, support among the public could continue to gain traction.

UBI once had more conventional support across the political spectrum in the U.S., garnering support from greats like Martin Luther King Jr. to even the less righteous like Richard Nixon. While their rationales for supporting basic income differed immensely, after the late 1960s and early 1970s the debate on basic income in the U.S. cooled down. Since the era of King and Nixon, UBI has been mostly reserved to the political fringes and wasn’t brought back into the mainstream until the 2020 Democratic Primary after being championed by former presidential hopeful Andrew Yang.

While Yang should be credited with elevating UBI back into the mainstream fold, his proposal and view of the social safety net should concern guaranteed income supporters. In his campaign, Yang seemed opposed to expanding the social safety net, failing to fully endorse and tip-toeing around policies like Medicare for All, national rent control, expanding Social Security and universal tuition-free college. His UBI policy would also have forced “entitlement” beneficiaries, like those who rely on food stamps, to choose between Yang bucks or benefits, effectively replacing elements of the social safety net. The policy would have relied on a regressive tax structure, in the form of a Value-Added Tax, which burdens poorer consumers at higher proportions than those with wealth.

Yang’s campaign rhetoric on the intersection between basic income and the social safety net also echoed the arguments made by those in Silicon Valley. Without the expansion of social infrastructure or consumer price controls, Yang’s “freedom dividend” (monthly payments of $1,000) by itself would do little to prevent increases in prices for essentials like rent or health care and could open the door to austerity.

Despite his rationale but in part to Yang’s credit — who is now running pilot programs in upstate New York and South Carolina — basic income is gaining attention. As the pandemic reveals a hollowed out economy, UBI and universal programs, like Medicare For All, are now nearing all-time highs in the U.S. According to Data for Progress — a think tank that ideologically fluctuates between centrist and left liberalism — on March 2 support for UBI in the U.S. reached 33 percent with opposition amounting to 48 percent. On March 17, support for basic income reached 58 percent, while opposition shriveled to 26 percent. In just 15 days, as the COVID crisis began to materialize, the U.S. public dramatically shifted their view on basic income.

Temporary adoption of a Spanish-styled minimum income policy in the U.S. would be a meaningful adjustment in protecting workers’ security during the pandemic. In the short term, basic income will stabilize the economy and ensure the public’s safety. Yet, economic challenges — which existed long before COVID-19 — have amped up since the calamity put the world on hold.

Since the 1980s, a precarious labor force has been forced into competition for stagnant wages, while rents and the cost of living continue to rise. High-paying, quality jobs have left and been replaced with unpredictable gig economy work, while capital has ventured out overseas to seek cheap inputs and higher profits. Blue-collar jobs are increasingly automated, while capital further saves on labor costs and boosts production. As the neoliberal project continues to churn, the economic contradictions of yesterday and the future await.

Looking down the road, a permanent, universal and unconditional basic income plan will help balance the inequities of yesterday, today and tomorrow. Ensuring workers a guaranteed income from the state is not just a temporary solution to the economic crisis triggered by the pandemic, but rather a long-term measure to counteract aspects of wealth concentration, stagnating wages, job flights overseas and increasing automation down the road.

With that said, UBI alone would have limited impact on improving the precarious lives of workers and isn’t an end-all-be-all policy. Questions of workers’ relationship to production would still remain. Yet when used with other programs that are democratically owned and universally administered, UBI could be another valuable lifeline that enforces class solidarity for a downwardly mobile labor force.

As countries abroad debate and move towards unconditional income, a short- and long-term policy in the U.S. awaits. With UBI, a stabilizing distribution of resources can be better achieved in the immediate term and the future. In easing pandemic uncertainty and promoting a post-pandemic recovery, a permanent UBI with large investments in social programs will increase solidarity, ease poverty and stabilize a volatile market that’s headed toward depression.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.