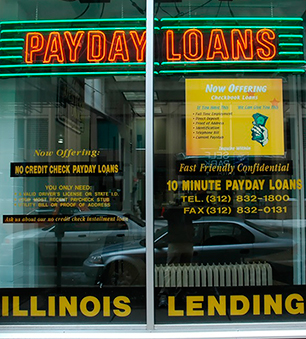

The first refuge of a payday lender defender is to point to the borrowers’ need for credit. A close second is to accuse opponents of being paternalistic or out of touch with the realities of would-be borrowers, whom they consider uneducated or unsophisticated. Lisa Servon, a professor at the New School of Social Research, relies on both refuges in several recent articles she’s written. She expressly states or strongly implies that we who criticize the “alternative financial services” industry have failed to actually situate ourselves in the communities we seek to protect. She then congratulates herself on being able to expose the “real reasons” why low-income communities and communities of color use these services.

Advocates have learned to respond to the first argument by exposing it for the red herring that it is. Of course people of all incomes need access to credit; the problem with payday loans is their predatory structure and cost. It is by now well-documented with unimpeachable data by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Pew Research among others that the form of credit peddled by payday lenders worsens rather than improves most borrowers’ financial situation.

Servon’s most recent essay includes the story of an employee at a payday lending store who uses payday loans herself. The employee took out five payday loans “ranging from fifty-five to three hundred dollars each.” Even using the most conservative estimate based on Servon’s numbers of one loan for $300 and four loans for $55, (total borrowed: $520), these loans cost her at least $475 (including $300 in overdraft fees), and she is still paying for them. Unable to pay the loans back, she had to “roll the loans over,” and later took a second job in the middle of the night to try to pay back the loans. She is now on a payment plan where she diverts $100 of her paycheck every week to pay each lender $20 for the loans she took out last summer.

The second accusation, however – that we are outside agitators, Ivory-tower academics or sanctimonious moralists – has more often been met with silence. It’s time for a reality check.

Servon’s essays not only fail to acknowledge the work of countless Latino, African-American and Asian-American advocates, many of whom are one generation or less removed from the very-low-income communities we represent, in them she reframes insights and arguments we previously have offered as the new, original product of her unprecedented research. In Servon’s world, neither the National Council of La Raza nor the National Coalition for Asian Community Development have called for linguistic and cultural relevancy in the delivery of financial services and the NAACP has not long argued for increased access to credit from banks that do not discriminate, intentionally or otherwise.

She also ignores that very many advocates of color work at social and economic justice organizations because of what we, our families and our communities have had to and continue to experience at the hands of all sorts of financial service providers. For example: “I’ll bet that most of the people crunching numbers for surveys of the unbanked and studies of payday lending have never set foot in one of these stores.” Or this suggestion: “Researchers, journalists, and policymakers routinely demonize the businesses that provide payday loans, calling them predatory or worse. Indeed, if you are not living close to the edge, it’s hard to understand why a person would pay such a high price to borrow such a small amount of money.”

We are not fantasists or idealists – we make arguments grounded in the realities of the industry and our communities. We conduct research to document and prove to others what we know intimately. We work with consumers to share their stories with regulators – especially when the law has been broken. As a result, our calls for reform are comprehensive, even on the “demand side” she says we’ve ignored. We’ve called for much more than mere financial education – we have made strong claims for the need for higher wages, lower-cost credit options from regulated institutions like credit unions and banks and stronger regulations and enforcement mechanisms that protect consumer interests.

Despite the fact that people of color who come from or are members of low-income, immigrant and other marginalized groups have been doing this work for decades, accusations that social justice advocates do not represent the experience of these communities always seem to go unanswered. Worse are those that use the claim to paint themselves as brave souls marching into uncharted territory, as if no one else has asked about the lived experiences and needs of low-income communities of color. Perhaps one reason why this strategy persists is because we advocates of color are also subject to the accusation of bias: Our insight, research and calls for reform are easily tarred as subjective and self-serving. We’re damned if we claim our community ties and damned if we don’t.

In the same way that we know how race, class and immigration status combine to affect a person’s ability to thrive, we also know the need for better financial services is inextricable from the broader economic forces at work. We recognize that the reason many of us feel comfortable with the employees of these loan businesses is because they, like so many low-income people of color, are making the best of the limited opportunities offered us in this economy. That is why, when industry lobbyists testify at city council meetings and other forums that they are providing jobs, we call out the need for better jobs with living wages and benefits and in industries that do not prey on the financial instability of our communities to profit.

In many of her accounts, Servon shares how she and her co-workers are friends with customers who are predominantly people of color. While not directly stated, we are led to believe that these “friendships” somehow negate or are more important than the structural racism and classism that maintains an industry that disproportionately targets neighborhoods where the majority of residents are low-income and/or people of color. If she took just one step back, it might come into focus just how the industry fuels the cycle of low wages and financial instability that creates the demand for its product. Friendship, in that context, is a survival mechanism, not a cure for what ails.

I have a few suggestions for her next article. First, inject real figures into the stories. Instead of relying on the industry tactic of representing cost as “$15 per $100 borrowed,” consider stating the actual total costs the customer pays and the equivalent annual percentage rate – a figure that is used to represent the cost of credit on every other type of loan. Second, write about the two-thirds of customers who are using payday loans to pay for ongoing household expenses rather than “unexpected emergencies.” What are the implications of putting people who are already on the edge financially into an even worse financial situation through these payday loans? Finally, take the time to learn about and build on work that has come before hers – she might tell a better story as a result.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.