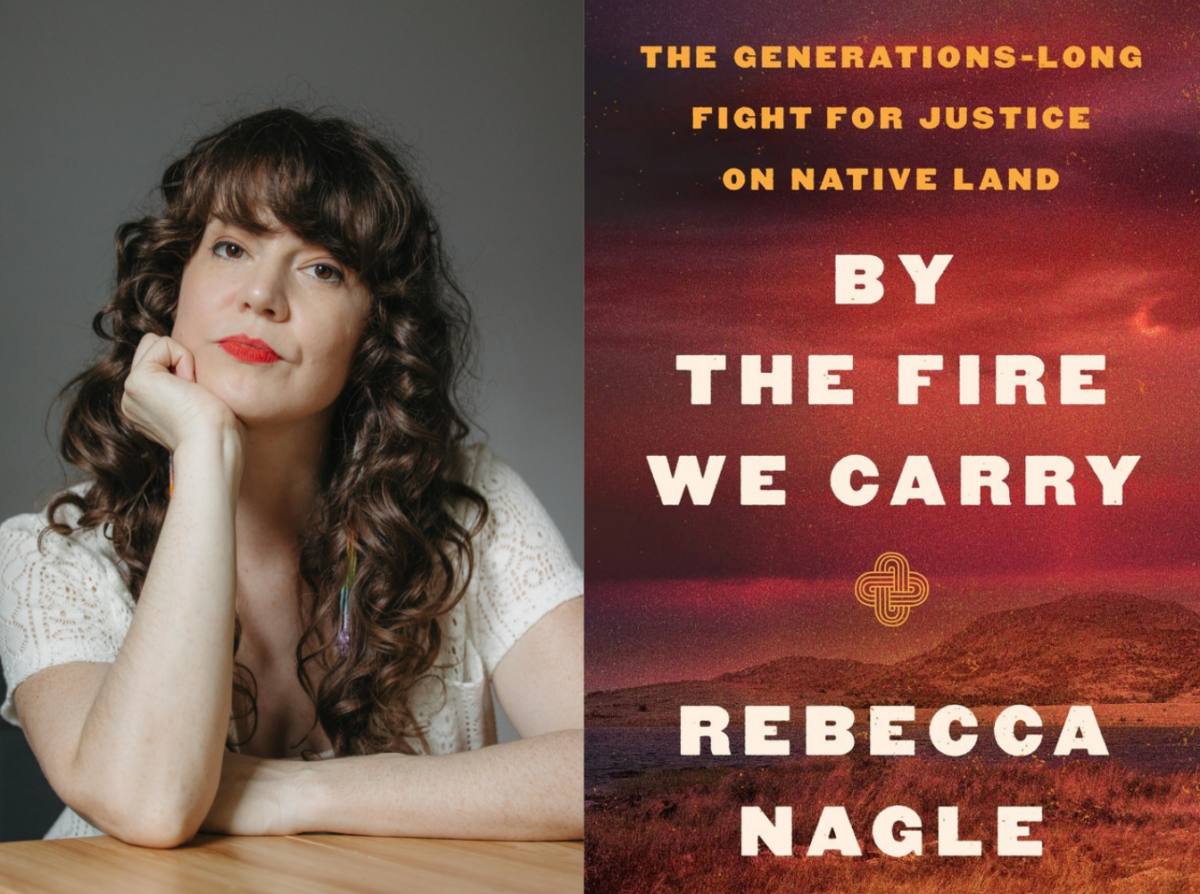

The Thanksgiving holiday is rooted in colonial myth-making. While many gatherings this week will be divorced from that mythology, this is nonetheless an important time to center Native histories and struggles. Rebecca Nagle’s new book, By the Fire We Carry: The Generations-Long Fight for Justice on Native Land, offers a vital resource for such reflection. In this meticulously researched effort, Nagle chronicles a generations-long fight for tribal land and sovereignty in eastern Oklahoma, weaving together a contemporary legal battle — an imprisoned Native man’s fight to avoid the death penalty — with historic wrongs committed against the Muscogee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee nations. In a time when the truth of history and of the present are under attack, By the Fire We Carry is an invaluable account of injustice, loss, survival, and reclamation. I recently spoke with Nagle about her book, what Native people will be up against under Donald Trump, and the histories people in the United States must understand if they hope to create a just future.

This interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.

Kelly Hayes: In the prologue of your book, you wrote, “I wrote this book because I believe the American public needs to understand that the legacy of colonization is not just a problem for Indigenous peoples, but a problem for our democracy.” Can you talk about how the legacy of colonization is a problem for democracy?

Rebecca Nagle: I think it’s twofold. I think that when it comes to Indigenous nations, there is a permissiveness when non-Native people want what belongs to Native peoples, and a weakness when it comes to our government’s will to defend those rights. And so, I think what you see over and over again in U.S. history is that the law is often ignored when it comes to Indigenous nations. Whether those are congressional statutes or treaty rights or Supreme Court precedent, the courts or states and different actors will break and bend the rules, and sometimes even rewrite the rules to fit settlers’ needs and wants.

So often when settlers want something that belongs to a tribe, whether it’s gold, oil, money, power, children, they get it, even when the law clearly protects the tribe. And I think that kind of lawlessness is corrosive in any kind of democracy. And so if we think that our government can be lawless and corrupt when it comes just to Indigenous people and never in any other area, I think we’re all kidding ourselves.

And then I think the other problem is a little bit more foundational. There’s a great legal scholar named Maggie Blackhawk who’s written about this. But when you think about our Constitution and the laws that govern our country, our founding fathers and their supposed wisdom, they wanted a government that would derive its power from the consent of the governed. But they also wanted an empire, and so they built both. A government that at its center, gave citizens a vote and an empire that as it expanded, constantly controlled the lands and the lives of people who had no say. And so while over the generations of American democracy, that center has changed, who is included in that center has changed, the edge of empire never went away.

And so, there have always been people who have lived under the raw power of our government, but not the liberties and the privileges of our constitution, from Indigenous nations, to residents of Guam and Puerto Rico, to migrants detained at our border. And so, I think that our inheritance as U.S. citizens is a democracy that can be wildly anti-democratic and a government that rules both by consent and by conquest.

You are meticulous in your description of the Sharp v. Murphy case. Can you talk about the significance of that case and the Supreme Court’s decision?

So the case, which eventually became McGirt v. Oklahoma, because of some complicated maneuverings of the Supreme Court, upheld the reservation of Muscogee Nation. That reservation hadn’t been recognized by the state of Oklahoma for over a hundred years. And based on the Supreme Court’s ruling, lower courts in Oklahoma interpreted it to apply to eight other reservations in the state — which taken together, cover 19 million acres, about half the land in Oklahoma and most of the city of Tulsa. It is an area that is larger than West Virginia and nine other U.S. states. And it constitutes the largest restoration of tribal land in U.S. history. And so, that’s the exciting significance of the case.

In your book, you alternate between chapters exploring the trajectory of the Sharp v. Murphy case and chapters that explore historical wrongs committed against the Muscogee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee nations. Why did you choose to alternate between recent and more distant histories in this way? What connections were you hoping to illustrate?

I think that the big connection I wanted people to feel is when the decision came down and Muscogee Nation won, for tribal citizens here in Eastern Oklahoma, it was a very powerful and a very emotional day. Of course, people were overjoyed, but I think there was also a lot of grief in the celebration. It was a joy that cut hard and deep, because I think that we knew how much had been lost to reach this one act of justice. I wanted non-Native people to have a sense of that, to have a window into that experience and to see all the history that went into this Supreme Court battle.

I also wanted people to see how much history has repeated itself. I think that we can get caught up in this story of progress, particularly in the United States. And this idea that there were some problems with our country early on, but things overall have gotten a lot better. And I think that Indigenous peoples, our story really problematizes and runs counter to those ideas of straightforward progress. And I think there’s a lot in the patterns of lies told about Indigenous people, excuses to take Indigenous land, the way that states and specific actors are always fighting Indigenous nations for power that really haven’t changed. There are historical patterns and political patterns that a lot of people might not be able to recognize. And so, I wanted to write that in a way that people could see it.

In your book, you write that “Indigenous resistance formed the first large-scale political protest movement in the United States.” A lot of people are unfamiliar with that history because, as you also state in the book, “the history of Indigenous peoples is barely known and the stories that are popular are mostly wrong.” What would you like people to understand about Indigenous resistance, and its role in the larger legacy of protest in the United States?

That’s a really good question. Southern states wanted to get rid of Indigenous nations living within their borders. They coveted that land, and for slightly different reasons, depending on the land, but in large part, to expand the slave economy and cotton production. And so, they got a friend in the White House named Andrew Jackson in the election of 1828. And his signature policy was the ethnic cleansing of Indigenous people from what was then the territorial limits of the United States. And that policy became a bill called the Indian Removal Act that went to Congress. And when it went to Congress, it was extremely controversial and it caused a really big geographic divide.So, there were white Christians in the north who were opposed to the bill and who organized the largest petition drive in the country’s young history. It was also the first time that women in the United States participated in a public political action. Women sent petitions to Congress at a time that was very controversial. There were speeches on the floor of Congress that literally went on for days. It was a really, really contested bill, and it barely, barely passed. The other thing that’s really interesting about the opposition to Indian removal, even though it failed, is that a lot of the people who were involved in that became involved in the abolitionist movement, which would reach its peak a couple of decades later.

I think people often assume that early Americans just hated Indigenous people and just wanted Indigenous land. Sort of that, you can’t judge history by today’s standards, kind of viewpoint. And actually, when you look at the primary sources, this policy was very controversial at the time. And it kind of had some themes of today where it was a policy that I think you could argue that most U.S. citizens at the time were opposed to. But the South because of the Three-Fifths Clause had an outsized representation. That’s how the bill was able to get through, which I think is parallel to some of the problems that we have today with what the majority of people want and what they are able to get because of how our electoral system is structured.

Next year, we are going to be faced with a second Trump administration. What are you concerned about, in terms of what Native people are and will be up against?

In the last Trump administration, we saw some policies that were hostile to Indigenous nations, such as the diminishment of the Bears Ears Monument. I think one thing that startled a lot of Native leaders was when his administration took the Mashpee Wampanoag land out of trust, which was the first time that kind of reversal had happened in many decades. I think that scared a lot of tribal leaders.

And I think too, when you look at the writings on the right, whether it’s like the Heritage Foundation or Cato or these sorts of right wing think tank places, for years, there has been this–it’s usually shrouded in languages of this sort of cloak of equality, of treating everyone the same. But when you drill down to it, they’re talking about getting rid of any kind of protections for tribal land, getting rid of reservations, or just getting rid of tribes in general. And so, I think that that’s the spectrum of what we’re looking at, that there could be specific policies that are harmful to specific tribes and specific regions. I think that was the goal of the Brackeen case, and it failed. I do think that there are actually a lot of Republicans in Congress who wouldn’t go for something like that. And so, I don’t know how realistic that is legislatively, but I think it’s a scary time.

And the other point I want to make, too, is that there was a lot of focus on policies that harm vulnerable groups during the Trump administration, and that focus was lost during Biden’s administration. And so these needs in our communities, they’re always there. And definitely, things have the capacity to get worse. We shouldn’t underestimate the capacity for things to get worse. Because I think we’re facing a time when that’s going to happen. But I think that the kind of concern that we have with Trump being elected is the kind of concern that we should always have, where Native people are concerned.

My last question is about the personal narratives in the book. You capture some very personal perspectives, from the relatives of George Jacob, whose murder is described early in the book, to your own perspective, as you made this journey through historical understanding. Can you talk about the importance of sharing those Native perspectives in your book?

I think that was something I thought about a lot. I think especially with history from a long time ago, when you do the research and you’re in the primary source documents, a lot of the primary source documents are written by white people. And so, I think it’s much easier to write the white perspective based on what’s available. I think Cherokee history is cool because we had our own newspaper and stuff. We actually do have a lot of records, but starting at a certain point. And so for me, that was something that was really important.

I think that I’ve read a lot of Native history where the Native people don’t have interiority, if that makes sense. Things are happening to them, but they’re not people with lives and feelings and internal conflict. And as a non-fiction writer, I can’t make those things up. But I try to interview people, spend time with people’s words, and really try to talk about my own family and my own personal connection, or interview the chief of the Muscogee Nation, and document his internal conflict, or use the victim impact statements from George Jacob’s family. And just really allow people to be real, which sounds so basic, but I think in a lot of writing about Native people, Native folks aren’t given that full humanity, or that interiority–as though we’re not complicated people. And so, I really wanted the people in the book to have that interiority as much as I could as a non-fiction writer.

Well, I really appreciate your book, and I hope this conversation reminds people that if we want to wage meaningful battles in the present, we have to be informed about the past.

Yes. There are a lot of parallels, I think, between Trump and Jackson. People are always comparing Trump to Mussolini or Hitler. But we don’t want to have to leave the United States to find the parallels. You want to talk about putting people in camps? We’ve done that. Our government shouldn’t have that power. It has that power because it’s done it before and we need to think about that.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.