In March 1976, we sat in a cavernous Chicago courtroom while FBI agent Roy Martin Mitchell testified in the federal civil rights case that we and our partners at the People’s Law Office had brought on behalf of the families of slain Illinois Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark and the seven survivors of the murderous pre-dawn Chicago police raid on their West Side apartment.

Thanks to the liberation of FBI documents from the Media, Pennsylvania FBI offices, the revelations of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Activities and our own hotly contested pretrial battles to uncover the truth about the raid, we had been able to document the local FBI’s central role in setting up the raid as part of the Bureau’s secret and highly illegal COINTELPRO Program. This program had previously targeted Black liberation leaders including Malcom X, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Elijah Muhammad and the organizations that they led. As the Senate Select Committee would later find in its April 1976 report, the FBI had more recently turned its attention to “destroy[ing] the Black Panther Party.”

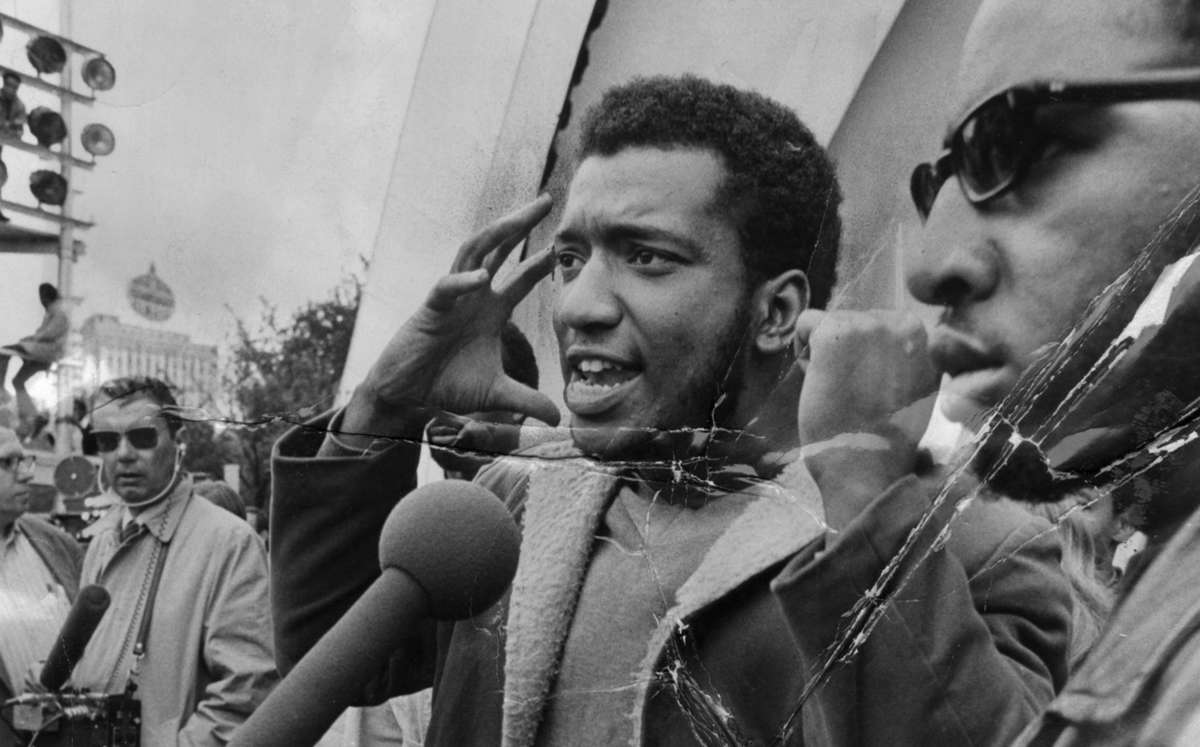

Roy Martin Mitchell was an integral member of the Chicago FBI office’s Racial Matters Squad and the control agent for a prized “asset”: informant-provocateur William O’Neal, who was the captain of security of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP). As such, O’Neal had ready access to the local BPP chairman, the dynamic Fred Hampton, who had garnered particular attention from Mitchell, his Racial Matters Squad and the COINTELPRO program.

At the time Mitchell testified, we had documentation of the FBI’s secret role in setting up the raid, including a detailed floor plan of the Hampton apartment — designating the bed on which Hampton would later be slain — that Mitchell and O’Neal had drawn up, and which Mitchell had supplied to the Chicago police raiders and their state’s attorney supervisors, including Cook County State’s Attorney Edward V. Hanrahan, who utilized this invaluable information to execute the murderous pre-dawn raid on December 4, 1969.

We also had obtained two other damning FBI documents: a December 3, 1969, document that claimed the impending raid as a COINTELPRO project, and a post-raid document that set forth the outlines of the conspiracy to cover up the FBI’s involvement in the raid.

Concluding from the Senate report and the liberated media documents that the raid and its coverup had to have been approved and ratified at the highest levels of the Bureau, we had sought, months earlier, to join as defendants in our suit FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Director of Domestic Intelligence William C. Sullivan, and George Moore, who, as boss of the Extremist Section of the Domestic Intelligence Division, had the Black Panther Party directly in his administrative sights. We had also journeyed to Washington to question Sullivan under oath in a pre-trial deposition, but his Department of Justice lawyers thwarted our efforts to probe the Bureau’s knowledge of the raid and COINTELPRO, and our overtly hostile federal trial judge, J. Sam Perry, acted similarly by denying our request for relevant documents and to bring Hoover and his crew on board as defendants.

So it was in March 1976 when Mitchell set about to meticulously slander Hampton and the BPP through the reports of his informant O’Neal. An instinctively cautious witness, Mitchell nonetheless made a crucial mistake, and in the process, revealed that the FBI and its government lawyers had suppressed 200 volumes of FBI files that pertained to Hampton, Clark, O’Neal, the seven survivors of the raid, and the FBI’s cover-up investigation — files that the judge had previously unwittingly ordered produced.

The government rushed Mitchell off the stand with the judge’s blessing, and, over the next two months, its lawyers produced (several files at a time), the 200 volumes of documents. The files contained a great deal of information relevant to our claims of FBI conspiracy, but the FBI and its government lawyers, perhaps hoping to stave off the inevitable, saved the smoking gun for last: a pair of documents to and from the Bureau in Washington and the Chicago office that were buried in O’Neal’s personnel file and which requested and obtained for O’Neal a $300 bonus for furnishing “a detailed floor plan of the apartment” that “subsequently proved to be of tremendous value” and “was not available from any other source.”

Incredibly, Judge Perry shrugged off the damning government misconduct, refused to grant a mistrial and forced us to continue with the trial as we attempted to read and digest the deluge of documents that we were receiving on a daily basis.

The trial lurched forward for another 15 months, making it the longest civil trial in federal court history. Both of us spent time in the federal lockup for protesting the outrageous rulings of the judge and the blatant misconduct of the defense. After the jury heard 18 months of damning evidence, the judge absolved not only Mitchell, O’Neal and their Chicago bosses, but also State’s Attorney Hanrahan and the 14 raiding cops who fired more than 90 bullets from a machine gun, a rifle, shotguns and handguns at the sleeping Panthers by entering a directed verdict in their favor.

Despite its relevance and our repeated discovery requests, the FBI and its lawyers never produced Mitchell’s personnel file as part of the 200 volumes, nor were we permitted to recall Mitchell to the witness stand in order to question him about the O’Neal bonus document and whether he had also been rewarded for his central role in setting up the raid and subsequently keeping the FBI’s role under wraps.

Thankfully, the litigation did not end with Judge Perry’s baseless and vindictive ruling. We appealed to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, which rendered a landmark 70-page opinion on April 23, 1979. The Court of Appeals granted us a new trial, ordered a hearing on the government’s misconduct and absolved us of our contempt citations. The Court held in no uncertain terms that we had amassed a powerful record of two successive police, prosecutorial and FBI conspiracies.

The first conspiracy, which was grounded in the COINTELPRO program and featured Mitchell and O’Neal’s central roles, encompassed the planning of the raid and the raid itself, and was designed, as the Court found, “to subvert and eliminate the Black Panther Party and its members, thereby suppressing … a vital, radical black political organization.” The second conspiracy, which included the post-raid coverup and legal harassment of the plaintiffs, was, as the Court further stated, “intended to frustrate any redress the Plaintiffs might seek and, more importantly, to conceal the true character of the pre-raid and raid activities of the defendants involved in the first conspiracy.”

We successfully withstood the defendants’ attempt to have the U.S. Supreme Court overturn the Court of Appeals’ decision, and the case was returned to another federal judge for retrial. We pressed for additional FBI documents, to join Hoover and Sullivan (both of whom were deceased), as well as Moore and several other high-ranking FBI and Department of Justice officials as defendants, and pursued the misconduct hearing. In order to avoid judicial condemnation of their suppression of the FBI files and, as it later turns out, discovery of additional documentation of the FBI’s role in the raid, the government joined with Cook County and the City of Chicago to settle our case for what was, at that time, the largest police violence settlement in federal court history.

At that point, in 1983, after 13 years of litigation, it seemed as if the historical record was complete and the true narrative of the raid established: Chicago police officers, under the command of the Cook County state’s attorney, and at the behest of the FBI and its COINTELPRO program, targeted BPP leader Fred Hampton, and assassinated him while he lay asleep as part of a murderous pre-dawn raid during which the police fired more than 90 shots that also killed Panther Mark Clark and left several other survivors badly wounded.

And so stood that record, until December 4, 2020, 51 years after the raid, when historian and writer Aaron Leonard received from the FBI a redacted copy of Mitchell’s personnel file in response to his 2015 Freedom of Information Act request.

Involvement of Hoover and FBI Officials

The newly released file, containing several hundred pages of FBI memos and reports, provides substantial evidence that would have contributed significantly to our examination of Mitchell and his Chicago supervisors. It also provides the first direct documentation that Sullivan, Moore and even Hoover were aware of Mitchell and O’Neal’s Black Panther activities; that they ratified, celebrated and rewarded O’Neal and Mitchell’s integral roles in the Hampton raid; and that they were involved in the early stages of the cover-up of the FBI’s involvement. Here is some of the key information contained in the documents:

- On June 27, 1969, in apparent recognition of O’Neal’s role in a June 1969 FBI raid of the Chicago BPP offices, Hoover commended Mitchell’s “very capable manner in which [he] performed in a matter of intense interest to the Bureau in the racial field … and for his “effective, skillful guidance of a confidential source who furnished valuable information.”

- On November 24, 1969, only days after O’Neal and Mitchell drew up the Hampton floor plan and initiated Mitchell’s plan to convince the Chicago Police Department to execute the raid, Chicago Special Agent in Charge (SAC) Marlin Johnson, who was a defendant in our suit, sent a memo to Hoover’s desk cataloging O’Neal’s important BPP-related activities, and recommending O’Neal for an incentive bonus. O’Neal’s activities are deleted from the document.

- On December 2, 1969, while the actual planning for the raid was in its final stages, Bureau Extremist Division Chief George Moore sent a memo to Bureau Director of Domestic Intelligence William Sullivan recommending that Mitchell receive an incentive award for “outstanding performance in the development of a highly productive informant in the Black Panther Party.”

- On December 4, 1969, only hours after the pre-dawn raid, the Bureau’s administrative division concurred with Sullivan, Moore and Johnson that the “performance of SA Mitchell in developing and guiding informant merits incentive award” in the amount of $200.

- On December 5, 1969, SAC Marlin Johnson “advised informant” (O’Neal) about an unknown topic; the remainder of this paragraph was redacted from the document, but it seems likely that it was to inform O’Neal that Johnson would be recommending him for a $300 bonus. Neither Johnson nor O’Neal ever admitted in sworn testimony that they met or had any discussion with each other on December 5 or any other time.

- On December 10, 1969, a memo sent from the personal desk of J. Edgar Hoover to SA Mitchell reads: “I am certainly pleased to commend you and to advise you that I have approved an incentive award in the amount of $200 for your outstanding services in a matter of considerable interest to the FBI in the racial field.… Through your aggressiveness and skill in handling a valuable source he is able to furnish information of great importance to the bureau in this vital area of our operations. I want you to know of my appreciation of your exemplary efforts.”

- On December 24, 1969, Mitchell sent an evaluation of O’Neal to Hoover stating, “He has been instrumental in the Chicago Office’s success in handling the Bureau’s interests regarding an extremist party in the nationalist field.”

- On November 6, 1970, Hoover provided Mitchell with another $200 incentive award for his handling of O’Neal, stating: “The manner in which you have developed and handled a source of information of great importance to the Bureau in the racial field is certainly commendable.… A great deal of the information which has been furnished by this individual has been of material assistance to the FBI in fulfilling its responsibilities.”

- On December 11, 1970, the Chicago FBI office sent a teletype to the FBI director marked “urgent,” which was initialed in Washington by George Moore, and discussed a redacted FBI agent’s (most likely Mitchell’s) potential testimony before a special state grand jury that was investigating the raid. At this point, O’Neal, Mitchell and the FBI’s role in the raid was still highly secret, and the teletype instructed that “any information dealing with [redacted]” — most likely the FBI’s role — “not to be touched upon” and “if any questions were asked in this area, [the redacted witness] is to immediately leave.”

As lawyers who were deeply involved in the Hampton litigation for 13 years, we view these documents as vehicles that would have opened up new avenues of questioning, led us to additional documents to pursue, deepened our proof of the assassination and cover-up conspiracies, and provided compelling proof that the highest level of Bureau officials, including Hoover, were partners in the conspiracies. As historians who have extensively written and lectured on the assassination, we welcome this unexpected trove of documents as further proof that the search for past truths continues into the future. We hope to assist Aaron Leonard — who has previously chronicled FBI surveillance and harassment of other 20th-century leftists — in his efforts to compel the FBI to reveal the redactions in the Mitchell files, and the pursuit of the secrets that still remain ensconced in the bowels of the FBI files will continue.

This search for historical truths about the government’s repressive tactics and programs continues to be of crucial importance to this day. While the official COINTELPRO program was terminated soon after it was discovered, government attacks on today’s radical movements have continued and intensified. The use of private security forces such as TigerSwan at Standing Rock; the utilization of more sophisticated spying and military technology (including drones, sound canons and concussion grenades) in Ferguson, Missouri; the targeting of the Movement for Black Lives as “terrorists” under the heading “Black Identity Extremists”; and the nationwide violent and coordinated law enforcement attacks on peaceful Black-led demonstrations in the wake of the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, as well as the most recent government-inspired white supremacist Capitol breach all demonstrate not only that the government’s repression mechanisms are alive and well, but also that law enforcement continues to be closely aligned with the emboldened forces of the violent and racist far right. The cold-blooded assassination of Fred Hampton provides an ongoing and detailed lesson about the illegal and violent lengths to which the government will resort to in its efforts to destroy social movements and young leaders of color when they pose a threat to its white supremacist power and control.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable work of Aaron Leonard, whose dogged pursuit of the Roy Martin Mitchell file uncovered the newly produced FBI documents detailed above.

5 Days Left: All gifts to Truthout now matched!

From now until the end of the year, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $50,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just 5 days left to raise $50,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!