Part of the Series

Struggle and Solidarity: Writing Toward Palestinian Liberation

In my inbox, there’s an email with a purple flier attached. Distributed by the Harvard Library, it depicts a white skull in a decorative hat, announcing a “Día de los Muertos” celebration. The event’s webpage boasts “performances by students and staff” and “remarks” from faculty. It was held yesterday in the Widener Library’s West Stacks Reading Room.

I had hoped to attend. Harvard has been my home for two decades. I am among the only 4 percent of its tenured faculty who are Hispanic or Latino. The event, which marks a traditional Mexican holiday honoring dead loved ones, is co-sponsored by multiple Latino student groups across campus.

I should have been there. But I wasn’t allowed in the building.

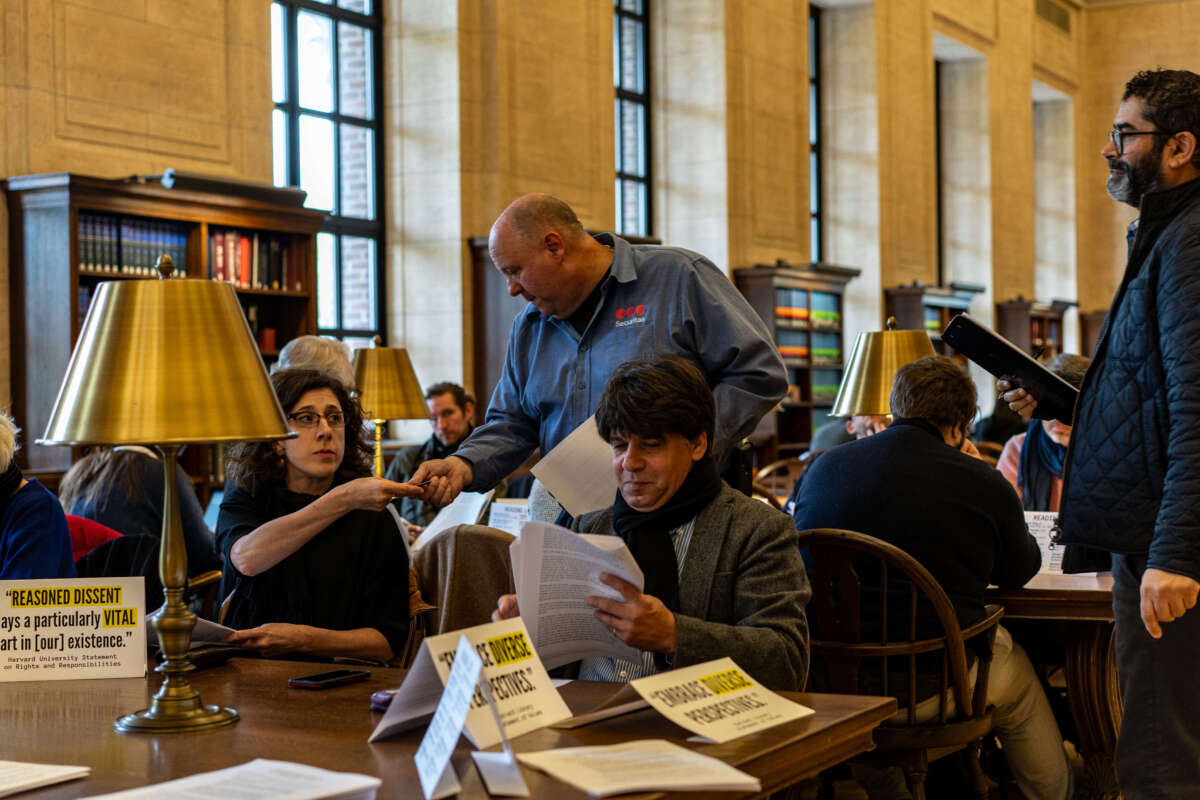

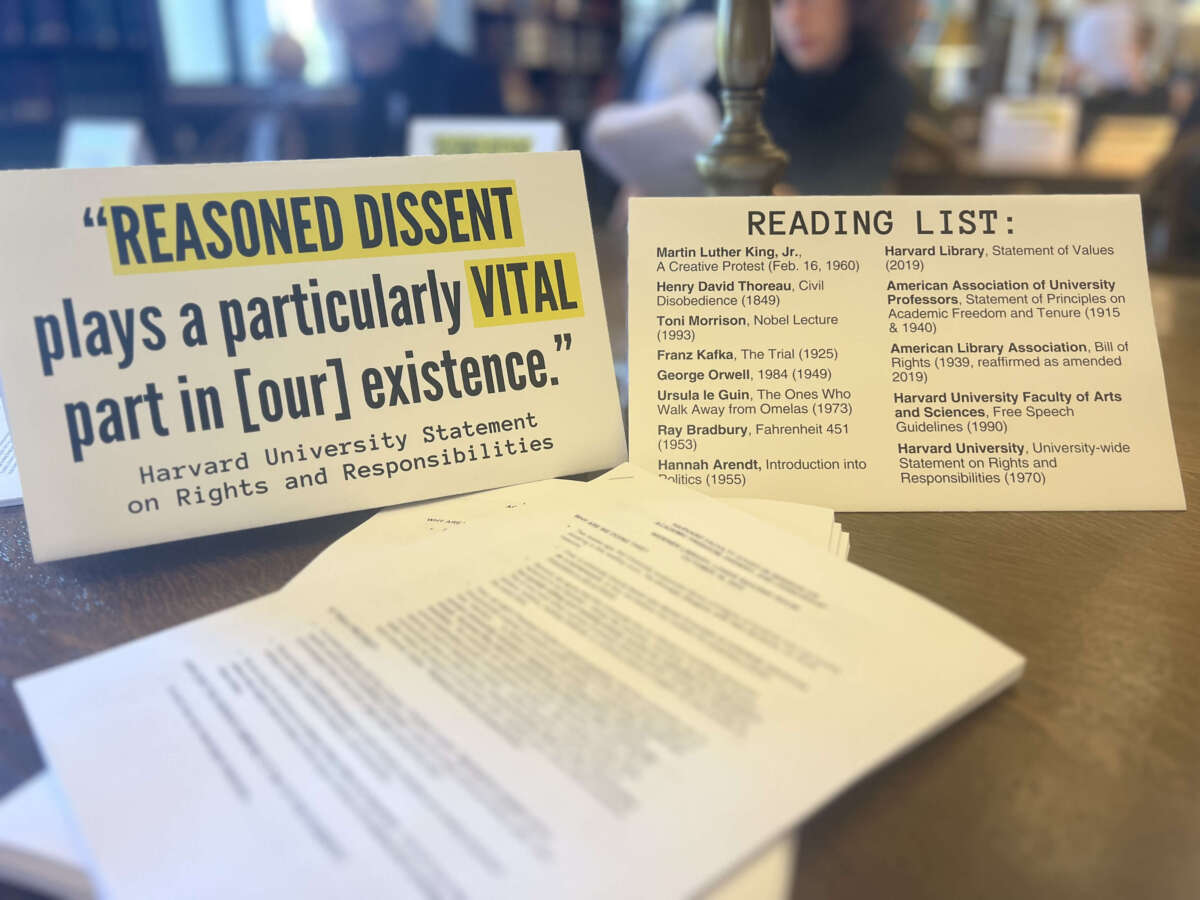

Two weeks ago, I walked into that same library’s main reading room with two dozen of my faculty colleagues. We sat down quietly at tables, reading texts about dissent and censorship while displaying small signs that quoted the library’s statement of values: “Embrace diverse perspectives.” We did not publicize the event in advance, and other library patrons continued reading quietly alongside us throughout the hour we were there.

We did this because, a few weeks earlier, the university suspended a dozen students from the library for doing essentially the same thing: reading silently, while wearing traditional Palestinian scarves and taping small signs to their laptops that said “imagine it happened here.” Like those students — and at least 60 others who have been disciplined since — my colleagues and I have been suspended from the library for our participation in a quiet study session.

With autocratic politicians banning books, outlawing library reading sessions and launching an all-out war on higher education in the U.S., one would hope to see university leaders resist dangerously illiberal attacks like these, not emulate them.

But Harvard has chosen a different path. In January, after our president was deposed by a right-wing pressure campaign and as student protests over the war on Gaza mounted, the university announced new “guidance on protest and dissent,” the first of many new protest-limiting actions that would follow over the ensuing months, at Harvard and at colleges across the country. According to this new guidance, “demonstrations” are “ordinarily not permitted” in “libraries or other spaces designated for study” and “quiet reflection.”

Is a quiet study session like the one I participated in a “demonstration” prohibited by these rules? Many faculty members, reacting to the students’ suspensions, say no. As Harvard Law School professor Noah Feldman writes, usually in a library the rule is that “as long as you are sitting at your desk silently, you can do whatever you want there.” In these study sessions, Harvard math professor Melanie Matchett Wood explains, the students “did not interfere with normal campus activity, and Harvard thus has no compelling reason to prohibit their speech.”

The university administration sees it differently. In an essay posted on the library’s website the day I was banned, Harvard’s vice president overseeing the library, Martha Whitehead, argued that a silent study session like the one I participated in “changes a reading room from a place for individual learning and reflection to a forum for public statements,” and thus strips these special places of their “vital role as places for learning and research.” Activity that “compels attention to a specific message” is “inherently disruptive and antithetical to the intent of a library reading room,” Whitehead concludes, “no matter the message” being conveyed.

I disagree with Whitehead that silent study sessions are inherently disruptive. And I reject her vision of libraries as catacombs designed to insulate people from external, let alone challenging, ideas.

When we showed up with small signs that read “embrace diverse perspectives” — a message literally printed on a banner outside the very room in which we sat — the library sent security guards to write down all of our ID card numbers.

But I also think her position is unabashedly hypocritical. Days after suspending me from the library for reading quietly at a table, the library hosted a Day of the Dead celebration, complete with music, food, large crowds and faculty remarks — in a reading room in the same building. If a silent study session is “inherently disruptive,” isn’t a large and festive gathering all the more so? If reading quietly with a small sign converts a reading room into “a forum for public statements,” don’t actual public remarks in a reading room do the same thing? In fact, is not the whole Day of the Dead event designed to “capture people’s attention” and convey “a specific message” — about the library’s purported mission to “cultivate and celebrate diversity,” perhaps?

Make no mistake, the Day of the Dead event was held in a reading room just like the one where my colleagues and I gathered to read. When Latino affinity groups wanted to use that space to host a party celebrating diversity, the library printed a flier and circulated it across campus. When my colleagues and I wrote to Whitehead the day before our study session, letting her know that we wanted to use the reading room to read, we got no response. When we showed up the next day with small signs that read “embrace diverse perspectives” — a message literally printed on a banner outside the very room in which we sat — the library sent security guards to write down all of our ID card numbers.

A few days later, Harvard’s chief librarian published an essay declaring our reading session about the importance of academic freedom and dissent — like the students’ earlier reading session about Gaza and Lebanon — “antithetical to the intent of a library reading room.” And then the university suspended our library privileges.

Why was our event treated so differently from the Latino groups’ Day of the Dead celebration?

The answer should be painfully obvious. Invocations of “institutional neutrality” notwithstanding, Harvard’s leadership is perfectly happy to make political statements, as demonstrated by President Alan Garber’s recent condemnation of a pro-Palestinian student group’s social media post and by a recent university-wide message condemning antisemitic stickers posted in Harvard Square. Harvard is also perfectly happy to use its libraries to convey political messages. That’s true when the university librarian invites photographers into the library to capture her alongside the first lady of embattled Ukraine, as occurred a few weeks before our faculty study session. And it is true when the library invites Latinos across campus to come to the West Stacks Reading Room so that we can “embrace diversity” on the Day of the Dead.

The fact that I cannot walk into the library this week to mark the Day of the Dead is its own political statement from Harvard’s leadership, one as tragic as it is ironic. Because Harvard’s onslaught of illiberal, speech-restrictive disciplinary actions — first against its students, now against its faculty — exists for only one reason: Over the past year, our students have been protesting about death.

Over 40,000 deaths. Dead children. Dead parents. Dead teachers. Dead students.

This Day of the Dead, the Harvard Library opened the doors of its West Stacks Reading Room to all those hoping to “gather to celebrate our departed loved ones” — except for those who had gathered there before to remember departed Palestinians.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.