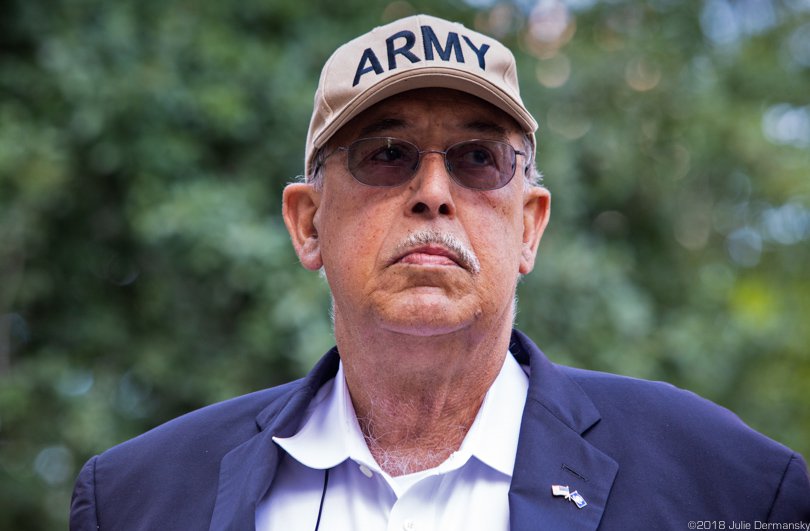

On the eighth anniversary of the BP oil spill, Retired Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré stood in front of the New Orleans Federal Court House and called “bullshit” on the court’s handling of claims made by those who participated in the cleanup efforts.

Thousands of workers BP hired to clean up the spill that polluted the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 have claimed exposure to oil and the dispersant has made them sick and still have not had their day in court. “It’s a crying damn shame we’ve allowed this in America,” Honoré said.

“Guess who don’t have their life back? The people who did the cleanup, the people who have to go home and get public assistance to stay alive, and it’s had an impact on their family,” Honoré said on April 20 at a rally aimed at seeking justice for cleanup workers.

Honoré joined cleanup workers and their supporters calling for federal judge Carl Barbier to reverse his decision to delay hearing remaining cases of cleanup workers indefinitely. They gathered before delivering a petition with 25,000 signatures seeking justice for the cleanup workers.

The petition states: “The Plaintiff Steering Committee walked away with $700 million; the Claims Administrator, in charge of processing the first round of payments to victims, walked away with $155 million dollars.” So far only $60 million has been paid “to a small fraction of the injured people who helped in the cleanup or lived in the designated zones.”

Jonathan Henderson, founder of Vanishing Earth, an environmental watchdog organization, helped compile the numbers cited in the petition from court filings and the medical claims settlement administrator, Garretson Resolution Group Status Report. He said he believes that justice delayed is justice denied. “People end up dying. They give up hope and they stop fighting. Time is what wears people down,” Henderson said.

Judge Barbier, the federal judge handling BP oil spill-related cases, made a controversial ruling in 2014 that affected a cleanup workers’ class action suit by siding with the oil company’s interpretation of a medical settlement agreement. Barbier ruled that those spill workers who hadn’t been diagnosed by a doctor before 2012 were not entitled to settlement payments in the class action suit.

Two recent scientific studies offered mounting evidence of the potential harms resulting from the oil dispersants, Corexit 9500 and Corexit 952, applied to break oil into smaller droplets during cleanup efforts in the 2010 spill.

A study by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences found that BP oil spill workers exposed to either forms of Corexit were more likely to experience a range of health symptoms such as coughing or burning in the lungs, eyes, nose, or throat.

In addition, a study from the Uniformed Services University, a federal government-run medical and health sciences school in Maryland, found that almost 2,000 members of the U.S. Coast Guard reporting exposure to oil dispersants experienced negative health issues, including “lung irritation, skin rash, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea,” more often than those who avoided dispersants or only had contact with oil.

I asked BP via email if the company would still use the same types of dispersant if there were another major oil spill but have not received a response. In the past the company has said the use of dispersants was approved by federal environmental agencies and the Coast Guard.

Nalco Environmental Solutions, Corexit’s manufacturer, donates to political action committees, according to public documents listed by the Center for Responsive Politics. A report by the center indicates that Nalco’s spending on lobbying the year of the spill increased dramatically. Payments in 2010 included $160,000 to Ogilvy Government Relations to lobby on Nalco’s behalf on “issues related to the use of Corexit in the Gulf of Mexico oil spill.”

Honoré likened the use of dispersant in the Gulf to the recent alleged chemical weapons attack in Syria and drew comparisons to the United States’ response: “We were poised to start World War lll over what the Syrians did to their own people, but here, we still haven’t held BP accountable.”

“These people are suffering from chemicals that our own government allowed a foreign company [BP] to put in our waters and poison our people,” Honoré said.

According to The (New Orleans) Times-Picayune: “Nearly one million gallons was dropped by air, and another 770,000 gallons was injected into the damaged wellhead about a mile under the water’s surface. It was the first time dispersants had been used on a large scale and in proximity to people.” The unknown impacts of this approach essentially turned the Gulf Coast into a giant petri dish.

At the April 20 rally, Capt. Joseph Brown spoke of seawater mixed with oil and dispersant getting into his boots and on his legs while working on a boat laying containment boom to keep spilled oil away from Gulf wetlands. He says that not only did this work impact his health, but it sickened his wife too, whom he says was exposed to the chemicals on his dirty clothes.

When George Barisich, a third-generation Louisiana commercial fisherman, found he couldn’t fish after the spill, he used his boat to assist in the cleanup effort. He said the oil and dispersant damaged his lung capacity and memory. He also asserted that not only did BP fail to inform workers of the potential hazards of Corexit, the company forbade workers from using respirators and threatened to fire workers who complained.

The U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) lays out standards and training for when oil spill cleanup workers should wear respiratory protection. In June 2010, a couple months into the spill, OSHA posted a worker education and training booklet that outlined how to deal with exposure to Corexit and other potential risks of oil spill cleanup. For Corexit, it recommended workers “avoid prolonged breathing of vapors. Use with ventilation equal to unobstructed outdoors in moderate breeze,” among other precautions.

Tiffany Odoms spoke on behalf of her dead husband Alonzo Odoms, who also worked the oil spill cleanup response. She described him as a healthy 45-year-old before the spill, who died two and a half years later after being diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a form of blood cancer. She has filed a wrongful death suit.

While thousands of people who took part in the BP spill cleanup have yet to have their cases heard in federal court, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke proposed opening almost all of the nation’s coastlines to offshore oil and gas drilling. In addition, Scott Angelle, director of the Interior Department’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement is rolling back key safety regulations put in place after the 2010 well blowout on the Deepwater Horizon rig to prevent another such human and environmental disaster.

Both officials have ties to the oil and gas industry. During his successful 2014 run for a Montana congressional seat, Zinke’s campaign received thousands of dollars from companies seeking oil and gas on public lands.

And the Department of Influence, a site the compiles information about the revolving door between special interest lobbyists and political appointees at the Department of the Interior, found that Angelle raised nearly half a million dollars in donations from oil and gas companies in his three unsuccessful bids for elected office in Louisiana. He has also made about $1.5 million since 2012 as a board member of oil and gas pipeline company Sunoco Logistics Partners, while also sitting on the board of the Louisiana Public Service Commission, which regulates state utilities.

Honoré, who founded the GreenArmy, a coalition of Louisiana-based environmental groups focused on fighting pollution, doesn’t mince words when it comes to regulatory capture. He often states that “our democracy has been hijacked by the oil and gas industry.”

During the April 20 rally, he placed blame on the Obama administration for what he says was letting BP off the hook so easily in the wake of the spill and faulted the Trump administration for what he described as its reckless proposals related to offshore drilling.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $240,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.