Member-owners of La Montañita cooperative in New Mexico have organized a broad coalition to “Take Back the Co-op!” In the process of trying to get their co-op back on track, they have uncovered some disturbing patterns in the national co-op landscape that raise alarm for the future health and integrity of local food co-ops all around the country.

The Impetus for and Goals of the Coalition

La Montañita is a 40-year-old cooperative with six stores in three cities. La Montañita’s first store was established in Albuquerque, New Mexico’s biggest city. About ten years ago the co-op acquired its first store in Santa Fe, an hour to the north. The co-op also has a store in the small city of Gallup, a couple hours to the west.

The goal of Take Back the Co-op! is straightforward: Return La Montañita to its mission, regain its financial health, re-establish good working conditions for employees, and adhere to the ecological values that are its foundation.

My main sources for this article, Django Zeaman and Dorothy Finnigan, say they’re not activists, but when they saw what was happening to their co-op in Santa Fe, it hit too close to home for them to ignore. Together with many others who are concerned about the fate of the co-op, they have collected the 1,600 signatures — 10 percent of the 16,000 member-owners— required by their co-op’s bylaws to secure a special membership meeting. In so doing, they’re following the playbook used by Honest Weight members to wrestle back our co-op from a board that was working with the management team to strip authority from the membership, under the guidance of costly consultants and attorneys. [Founded in 1976, Honest Weight Food Co-op is a large co-op in Albany, NY.]

First Inklings; the Clean Fifteen

Django said that their suspicion that something had gone awry with the co-op began with “a funny email in March.” The message introduced La Montañita member-owners to the “Clean Fifteen,” a new program the co-op was instituting to bring in fruits and vegetables grown conventionally — with chemical pesticides and fertilizers. “Clean Fifteen” is a term coined by the Environmental Working Group and refers to 15 types of popular produce that on average contain lower levels of pesticide residue than other tested produce. The rankings do not account for the pesticides on the non-edible portions of the produce, or the amount of pesticides used in the fields.

That email so surprised Django that he sent back an email, questioning whether the co-op really meant what it said. Up until then, La Montañita had almost exclusively sold organically grown produce. Almost all of its fruits and vegetables were certified organic, with occasional offerings of non-certified organic produce from local farmers. But earlier this year, without any member-owner knowledge or input, the current management ended that practice and even changed the Produce Mission Statement.

Town Hall Meetings Held

Town Hall Meetings Held

Evidently, many other member-owners pushed back as well, because La Montañita held a series of town hall meetings. At the Santa Fe meeting, 90 to 95 percent of those who spoke strongly opposed “Clean Fifteen,” Django said. “We were expecting that the co-op would scrap its plans,” he explained, “but that’s not what happened.”

That town hall meeting was the first time Django and Dorothy had seen La Montañita’s new general manager, who’d been hired in December. He had come to the co-op after working at multiple conventional grocery chains, including Sprouts, Safeway, and Winn Dixie. “We noticed he was rather deceptive,” Django said. “People in the audience would call him out on financial information about our stores and only then would he admit it.”

The town halls provided a chance to network with other concerned member-owners, resulting in ad hoc new groups in Santa Fe and Albuquerque. There was also a third group — the LaMontañita workers. By late spring, the three groups came together. In sharing information they began to piece together a fuller picture of what was going on.

Employee Issues Troubling

Just as member-owners saw the “Clean Fifteen” program as contrary to the ecological values enshrined in La Montañita’s mission statement, they also were discovering that management was disrespecting employees. Seeing that these core values didn’t seem to matter anymore opened many member-owners’ eyes.

Django said they’ve been hearing from employees about their experience under the new general manager’s regime. They say he enforces a culture of fear and intimidation and demands allegiance to him, with statements like, “I want 100 percent of you to love me.” A number of co-op employees have built careers at La Montañita and now the environment has become inhospitable. Some have resigned and a few people have been fired.

Dorothy said her involvement with Take Back the Co-op has been motivated by the “disturbing and disheartening” decline in working conditions at La Montañita. “As member-owners I feel like we have a responsibility to stand up because [the employees] can’t,” she said.

Attempts at Communication Prove Frustrating

From spring into August, the new ad hoc coalition tried to open up communication with the board to no avail, Django said. At the start of each board meeting, 15 to 20 minutes were set aside for member comments. After that, they could silently observe the regular board meeting, until the board went into executive session.

Django said, “We noticed that the general manager did most of the talking.” That was interesting and unsettling, given the crucial role of the board in representing member interests and viewpoints, supervising the general manager, and providing fiduciary oversight of the organization.

At the June board meeting, the general manager spoke about revenue, but he didn’t say a word about profit. The concerned member-owners recognized this as a major flaw in his presentation, but board members said nothing. At one of the meetings the board president stated that when it comes to business, they “don’t know sh*t from Shinola.”

La Montañita’s Financial Situation Telling

Take Back the Co-op sees La Montañita’s financial problems as symptomatic of its overall dysfunction and straying from the interests of its owners and employees. Three years ago, the co-op opened its sixth store. Of the four big stores, the three that do best function like neighborhood markets. But the newest large one is located in a big box shopping mall, surrounded by chains like Petco, Dick’s and Bed Bath & Beyond. It has consistently lost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

Though these losses are impacting the financial wellbeing of La Montañita as a whole, neither management nor the board has seemed willing to address the underlying situation — that this store is hemorrhaging money. Instead, the board and general manager have tried to explain the situation away by telling member-owners that the financial problems are because of “the new normal” of increased competition, Django said, but “the financial reports show that it’s almost entirely due to the new store that was opened three years ago.”

More Communication Troubles

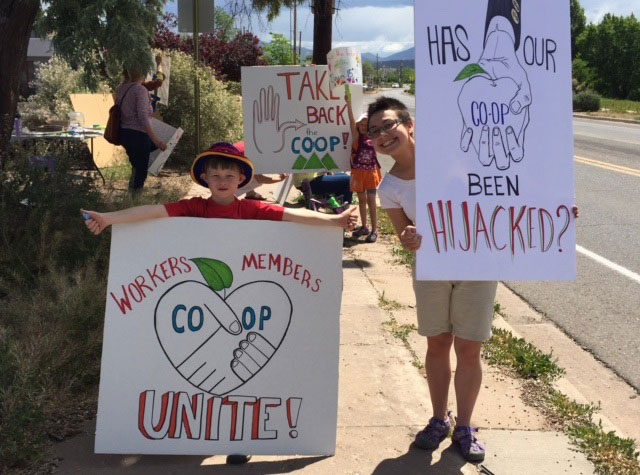

(Photo: La Montañita Co-op member, Santa Fe, New Mexico)

(Photo: La Montañita Co-op member, Santa Fe, New Mexico)

“We asked for a full membership meeting with the board on all the issues. We wanted them to be transparent,” Django said. The coalition presented a letter to the board signed by 500 people. They were demanding a meeting where member owners could ask questions of the board of directors. It would be a chance to clear the air.

Not only did the board refuse to hold such a meeting — they even declined to meet individually with member-owners! Then “a couple of us and a couple board members were supposed to meet, but a few days before the meeting, they said the general manager would have to be present,” Django said. “But we knew he was a large part of the problem.”

After that impasse, La Montañita rolled out a plan for its own meetings. The general manager and board president would participate in each meeting along with up to 10 member-owners. “People could talk about issues but they couldn’t get answers,” said Django. The meetings wrapped up with the message that member-owners need not be concerned. He said relatively few people attended.

La Montañita has tried to prevent concerned member-owners from reaching out to other member-owners. It wouldn’t allow them to table in front of its stores or to contact the membership. Meanwhile, Django said, the co-op has had employees on the clock sitting at a table, giving out a letter from the general manager in an attempt to counter the efforts of Take Back the Co-op!

Website Connects the Dots and Provides a Resource

In September the coalition launched its website TakeBackTheCoop.com to document the struggle underway at La Montañita. In addition to bringing La Montañita member-owners up to speed, the website is already providing an essential resource for members of other co-ops facing similar challenges. And Take Back the Co-op has begun hearing from people in other co-ops in distress around the country.

Several months back, when people involved with Take Back the Co-op started doing their own research, Django said, “We realized something bigger was going on.”

The website traces the problems at La Montañita to major players in the national cooperative sphere, most notably CDS Consulting. With 40 consultants, CDS, which stands for Cooperative Development Services, exercises a near monopoly on board training and education in the food co-op movement. CDS works hand in hand with two other major players. United Natural Foods Inc. (UNFI) is a publicly traded food distributor with $8 billion in annual revenue. The association of food co-ops known as National Co+op Grocers (NCG) is tied to UNFI through the purchasing contract offered to its members.

A couple of personnel changes at La Montañita suggest the interlocking nature of these entities. The co-op’s former board president was hired as a CDS consultant. One of her assignments has been consulting for La Montañita! “We paid for the privilege of her managing our stores,” Django said. Similarly, two of La Montañita’s general managers have been promoted to positions at National Co+op Grocers (NCG).

(Photo: La Montañita Co-op member, Albuquerque, New Mexico) Tabling for Petition Signatures, and other Public Outreach

(Photo: La Montañita Co-op member, Albuquerque, New Mexico) Tabling for Petition Signatures, and other Public Outreach

On the Saturday that we spoke, Take Back the Co-op was holding six different events to collect signatures on its petition. “The sidewalk near our stores — that’s public space,” Django said. He and Dorothy and numerous other member-owners have been tabling weekly at the popular Albuquerque and Santa Fe farmers markets.

“We’ve been talking with people who had noticed things were changing, but didn’t understand what was behind it. Awareness is key,” Django said. They’ve also begun to interest the media in La Montañita’s story. In September Django and Dorothy appeared on KVSF radio for an hour-long segment. “We were supposed to be on for 20 minutes but the radio host kept asking us to stay,” he said.

Doing public outreach has resulted in some remarkable encounters. David Bacon was tabling at the farmers market when a long-time co-op employee stopped to talk. David said that the employee was so afraid that he acted like he had post-traumatic stress. “The employee took us into a corner so no one would see us. His eyes were darting around,” he said.

Management Attempts to Silence Dissent

Since the Take Back the Co-op website launched in early September, management has redoubled its effort to suppress dissent among workers. Django said they started scanning employees’ Facebook pages to see if they had posted anything about Take Back the Co-op. Some of them have even been reprimanded by the head of human resources for what they posted on their personal Facebook page. La Montañita sent its employees a letter instructing them not to comment if a customer asked for their opinion about Take Back the Co-op and asked them to sign a document agreeing to abide by this policy.

“These attempts to squelch worker voices and clamp down on folks are only making people more impassioned,” observed Dorothy.

Bigger Goal

The community has been galvanized by their newfound awareness. Though the work is only beginning to restore cooperation and integrity at La Montañita, Django and Dorothy are aware of the bigger goal on the horizon; being of help to member-owners from other co-ops who are seeking to undertake the project of taking back their co-ops, too.

This piece was first published online in the October 2016 edition of The Co-op Voice, a monthly newsletter by and for members of the Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, New York.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $125,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.