Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

Early one quiet morning in September 2013, Carlos Oliva-Sola, 23, was fatally gunned down by two Los Angeles sheriff’s deputies in East Los Angeles. The shooting was over within seconds, but the echoes from those five deadly gunshots and the terrified cries of Oliva-Sola – “No! No!” – reverberate to this day.

At first, the reasons given by Sheriff’s Deputies Anthony Forlano and Nicolas Castellanos for opening fire on Oliva-Sola appeared to tick all the requisite boxes. The deputies claimed that Oliva-Sola apparently matched the description of someone seen carrying a gun in the vicinity; that Forlano had felt a gun in Oliva-Sola’s right pocket; and that, after a struggle between Forlano and their suspect, Oliva-Sola was reaching for his gun when they opened fire.

Oliva-Sola was found unarmed where he lay dying, though the deputies allege that they recovered a gun at the spot of a prior struggle. During the hours and days that followed, however, what had first appeared to be another grim though unremarkable entry into the chronicle of Los Angeles’ crime history darkened into something more troubling.

Forlano had been involved in six separate, non-fatal shootings prior to killing Oliva-Sola. At least three of those incidents involved unarmed victims.

Witnesses describe Oliva-Sola being beaten on the ground prior to being shot – contradicting the deputies’ story – while a grainy video of the shooting shows Oliva-Sola calling out helplessly as deputies open fire. What is more, Oliva-Sola’s family struggles to believe that he was ever carrying a weapon. Neither family nor friends recall ever seeing Oliva-Sola with a gun, and because he had no gang affiliations and no history of gun violence, they wonder why he carried one on that particular night at that particular time, when returning home after visiting a friend.

Casting perhaps the gravest pall over the case is the matter of Forlano’s own police record. He had been involved in six separate, non-fatal shootings prior to killing Oliva-Sola. At least three of those incidents involved unarmed victims. Forlano had also twice been removed from field duty; he had returned to field assignment the second time prior to shooting Oliva-Sola.

What is more, despite a Los Angeles district attorney’s report into the shooting that finds both officers had acted “lawfully in self-defense and defense of each other,” the same report contains factual errors and contradictions, and throws up many pivotal but unanswered questions.

Uncertainty keeps the wounds from that day raw for those who knew Oliva-Sola. In the living room of his home, his mother and sisters maintain a shrine to their son and brother – a large collage of photographs under which candles burn night and day. His father keeps boxes of documents and newspaper clippings related to the shooting that he scours through even now in an effort to find the one vital clue that will prove beyond all question that his son was killed needlessly. Oliva-Sola’s two closest friends have both struggled to hold together the threads of their young lives.

“I don’t think it was the bullets that killed my son. I think it was fear that killed him. I think it was fear of the police.”

They all remember a quiet, hard-working young man who, despite enduring a tumultuous few years – the painful fallout of his first and only relationship turning sour – had once again found some footing in his life.

Tellingly, having gone door to door with a Spanish-speaking translator in and around the streets where Oliva-Sola lived and died, what emerged is a portrait of a neighborhood of professionals – teachers and health-care workers, for example – who live in fear of crime, but who live in greater fear of those policing the crime.

“I don’t think it was the bullets that killed my son,” Olga Sola, Carlos’ mother, said in Spanish one ink-dark evening recently on the steps in front of her home. Sola is a short woman, careful about her appearance, always nicely dressed. She won’t leave home without a lick of makeup. Staring off over the city as she spoke, lights from surrounding apartments glinted in her watery eyes. “I think it was fear that killed him. I think it was fear of the police.” (From here on, Carlos Oliva-Sola, his family and friends will be referred to by their first names.)

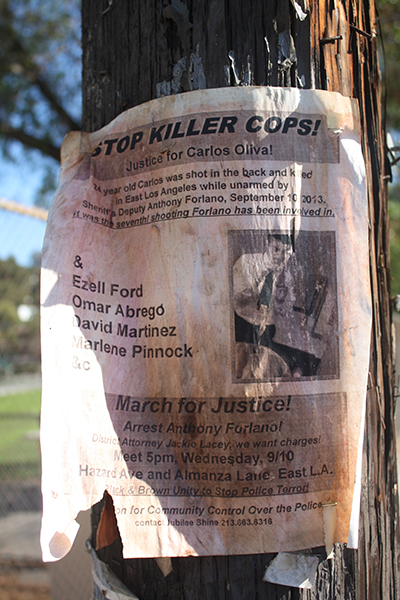

A flyer bringing attention to the march held one year on from when Carlos Oliva-Sola’s was killed by two LA sheriff deputies. (Photo: Daniel Ross)

A flyer bringing attention to the march held one year on from when Carlos Oliva-Sola’s was killed by two LA sheriff deputies. (Photo: Daniel Ross)

A Life Cut Short

July 23, 1990, dawned on another torrid, sticky Los Angeles morning on a day when many of the nation’s eyes were turned toward then-President Bush’s nomination of David Souter for a seat on the Supreme Court. The attention of Olga and Erick Obdulio Oliva, however, was focused on their new son, born at 7:37 am at the Martin Luther King Medical Center – an uncomplicated birth followed by a complicated early childhood marked by his parents’ split.

Despite the muddle of those early years, of a string of different homes, Carlos grew close to both his sister Bianca and his mother. He was well mannered and obedient around his family – the way he remained throughout his life. His mother recalls that he never once raised his voice to her, never once talked back.

The tides of unrest turned when the family moved into a small apartment in City Terrace in East Los Angeles when Carlos was 5. Balanced beside a steep alley sloping off Woolwine Drive, the apartment – on its doorstep a panoramic view of the San Gabriel Mountains that turns a paint-pot of colors at sunset – epitomized the wide possibility of this new beginning. Within a few years, Olga started a new relationship with Juan Delcid, who would become Carlos’ stepfather. The small apartment finally brought Carlos stability; it remained his home for the rest of his life.

A childhood of BMX stunts, DVD movie nights and after-school rock bands hadn’t prepared Carlos for life in jail.

Carlos was a solid student, neither excelling in any particular discipline nor left behind, although he did well in math, history and English, and was musical too. Having been a heavy child, Carlos grew conscious of his weight as he became a teenager; sports became a growing influence in his life. He was a keen football player, but far from being the popular jock, Carlos had few friends his own age – his shyness so overwhelming at times that when his voice began to crack he was often embarrassed to speak aloud. At 15, he finally found a small but solid clique of friends.

In David Lopez, four years younger, Carlos discovered a kindred soul. They took the same morning bus together, David heading to his middle school before they met up again after school, sometimes to play in a garage rock band, Carlos on the bass guitar or drums, which he had taught himself how to play. Jose Torres, the same age as David, the same quiet air, joined soon after, folding easily within the tight dynamic. Together, the three were inseparable.

They spent their evenings after school and weekends on their skateboards and BMX bikes in the parks and winding narrow streets that veined around City Terrace, and studied YouTube clips of stunts before attempting to recreate them. The part of the “older brother” to David and Jose was a natural fit for Carlos. Later, when his mother was unable to return home from a trip to Guatemala for a number of months, he and his stepfather Juan shared responsibility for his three other siblings, both while holding down full-time jobs.

Hard work didn’t faze Carlos. After graduating high school, he found a menial position at a nearby liquor store before Juan found him a job as a suite runner at the restaurant where he supervised – the Levy at the Staples Center, at the heart of a prospering downtown LA. There, Carlos quickly found a groove. He was reliable and liked by the other workers. The long, late hours – often he was there from 3 pm until midnight – mattered little. Things were going well, especially now that he had a girlfriend.

Michelle Juarez was sitting alone in their local library when Carlos noticed her from afar. He was afraid to speak at first. But Michelle knew through friends that he liked her. She played on this knowledge, flirted with other boys to make him jealous until he summoned the courage to ask her out.

Carlos impressed his boss with his work ethic and disposition, and he was promised more permanent work.

Carlos saw Michelle as his soul mate, and confided in her secrets he wouldn’t share even with David and Jose. She was his first and only love. But while he was the one who wrote poetry and love songs on the guitar, Michelle very much dictated the rhythm and pace of their relationship. She chose the movies they saw, the places they visited on road trips. And around the middle of July 2012, she drew it to a close after three years together.

Carlos, naturally silent, depressive, fell into a slump, unable to accept that it was over. And things came to a head on the first of November that year when he was arrested and charged with harassment and for sending threatening calls and messages (California Penal Codes 646.9 (a) and 422 (a)). Bail was set at $150,000.

Despite Michelle’s subsequent attempts to drop the charges against Carlos, he was taken to the North County Correctional Facility where he remained for 216 days – again a discrepancy appears in the district attorney’s report where it incorrectly states 433 days, twice the actual time – before he eventually stood trial and was immediately released.

A childhood of BMX stunts, DVD movie nights and after-school rock bands hadn’t prepared Carlos for life in jail. To survive, Carlos turned back into himself – the only bright moments arrived with regular visits from friends and family. Michelle’s parents visited him too, upset over the way he had been treated, Olga recalls. Carlos turned to religion, and kept a journal as a chronicle of his time inside, filled with dates of telephone calls he made, song lyrics and poetry.

He was an eloquent letter writer, with neat, bold handwriting that often betrayed conflicted emotions. Below is an excerpt of a letter he wrote Jose:

It’s getting close to two months since I was arrested. I can see time going by pretty fast, but I can’t seem to stop stressing. . . .

I hope I come out in five months, I’ll be happier than I’ve ever been in my life. This will be the worst ever Christmas and New Year, but I’m still grateful to be alive and well. I’ve found new hope in God.

I won’t be around for your birthday, for sure, but I hope you have a good day and a happy 2-year anniversary with Helen. Treat each other right, always. Don’t fight. Look at what happened to me. But oh well, I’m in here pretty unfairly. All I can do now is suck it up.

He complied with all court-ordered programs and on June 4, 2013, Carlos was convicted of the charges and immediately released – though placed on five-year parole.

Life outside initially proved tough; his criminal conviction was a stain on his record that few overlooked. He was unable to return to his old job as a suite runner at the Levy, and became frustrated as each new job he applied for turned him away. But aware of how easily he sunk into depression and self-reproach, he kept busy, channeling his energies into losing the weight that he had gained in jail. He ran around the neighborhood, went to the nearby park to work out, sometimes taking the bus to Gold’s Gym downtown, and whittled his broad 5-foot-8 frame down to a little over 190 pounds.

His mother kept a close eye on Carlos, and accompanied him to scheduled meetings with his parole officer. Soon after his release, however, Michelle contacted Carlos. And though he was reluctant to do so at first, and though his family and friends were apprehensive, Carlos and Michelle got back together – for good this time, they both believed. They discussed their life together, talked of starting a family, of Carlos eventually becoming a chef.

After Michelle moved temporarily to Texas for work, Carlos found a job as an usher with a firm that provided security services at special events. And for a week, he, Jose, David and a platoon of other workers crammed into a van early in the morning before they headed to a synagogue in West Los Angeles during Rosh Hashanah. Carlos impressed his boss with his work ethic and disposition, and he was promised more permanent work. Despite all the obstacles he faced, Carlos was beginning to see a glimmer of light through the gloom.

The Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department refused requests by Truthout to see copies of Deputy Anthony Forlano’s personnel file on the grounds that the investigation is still ongoing. The LASD also denied requests to see all records pertaining to Forlano’s six prior shootings, as did the Los Angeles district attorney’s office. Nevertheless, a number of documents concerning those six shootings have already been made public.

• On the evening of February 12, 2004, Forlano was one of two deputies who shot David Zamudio, wounding him in the right buttock. Both deputies said they believed that he was armed. When additional sheriffs arrived, they searched Zamudio and discovered that he was unarmed.

• Exactly seven months later, Forlano shot Salvador Montoya, who, during a struggle with another deputy, is alleged to have reached for that deputy’s gun. In response, Forlano held his gun approximately five inches away from Montoya’s stomach and shot him once. The deputy’s gun that Montoya was allegedly reaching for had remained in its holster. Montoya survived his gut-wound injury, took the case to court and was awarded $150,000.

• After the deputy’s fifth shooting on August 1, 2008, he was removed from the field. He was transferred to the Community Oriented Police Services unit before subsequently returning to the field.

• After a high-speed chase on February 14, 2011, Forlano and another officer opened fire on Osvaldo Ureta, inflicting eight gunshot wounds, though none fatal. Both deputies suspected Ureta of possessing a semi-automatic handgun. No gun was found in the car when Ureta surrendered.

After this incident, Forlano was again removed from the field. But after he complained to then-Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, Forlano was allowed back on the force, according to a letter to Los Angeles county supervisors written by Michael Gennaco, chief attorney for the Office of Independent Review. The letter states that Tanaka had not consulted with then-Sheriff Lee Baca before allowing Forlano back to work in the field. The letter also revealed that Forlano was not working for his unit when the shooting on September 10 took place. Rather, he was working an overtime assignment for the East Los Angeles Station.

When Carlos’ family announced in September that they were filing a $10 million lawsuit for damages against Forlano and the County of Los Angeles, it was reported that Los Angeles County Inspector General Max Huntsman, the man charged with overseeing the sheriff’s department, would be given power to investigate the case. At the time, Huntsman said that he wanted to review all reports pertaining to Forlano’s past shootings.

Forlano has been assigned to the Emergency Operations Bureau, said Lt. David Coleman of the LASD Homicide Bureau.

Carlos Oliva-Sola, and an unnamed date at a Quinceanera. (Photo: Daniel Ross)

Carlos Oliva-Sola, and an unnamed date at a Quinceanera. (Photo: Daniel Ross)

September 9, 2013

That morning marked the dying vestiges of another cloying heat wave in Los Angeles, and Carlos woke fretful after a restless night. He and Michelle were traversing another rocky patch in their relationship. Because of the job she had taken in Texas for a few months, the distance between them had brought to the surface some of his old insecurities.

The main source of his anxiety concerned a minor traffic ticket, for an expired driver’s license that he had received and forgotten about. Only, crinkled and folded so many times, the due date for his court appearance was faded and illegible, and he was worried how this would affect his parole if he had actually missed the court date.

Carlos called his mother – who was in Las Vegas with her husband Juan – for her advice, then headed early that morning to the Los Angeles Superior Courthouse in downtown to resolve the matter. Panicked, however, he left before he spoke with anyone, fearing that he would be arrested. He called his mother again, who managed to assuage his fears; she assured him that she and Juan would soon be on their way home, and that she would go with him the following day to sort it out.

“I love you mama,” Carlos replied, before he headed out into the night. It was the last time Olga saw her son alive.

Back home, Carlos didn’t want to be alone. He called both Jose and David and asked them over. Jose was working, but after David arrived, they planted chairs outside the front door of the apartment and slowly sipped glasses of tequila – neither of them big drinkers. Carlos, melancholy and reflective, steered the conversation frequently over the past. Before them sprawled East Los Angeles – a muddy sea of roofs that swallowed up the liquor store where Carlos got his first job, and Woodrow Wilson High School where they had both gone to school.

When Olga and Juan arrived home early that afternoon from Vegas, Juan pulled a chair up beside them and cracked open a beer. Though anxious still, Carlos was feeling a little less despondent about the ticket, given his mother’s promise to help him fix the problem. And as the evening closed in, Carlos decided to visit an old school friend who lived about 20 minutes away on foot. Olga didn’t want him to leave home after nightfall. But Juan assured her that Carlos had stopped drinking hours earlier – having already substituted tequila with a Red Bull – and that he would be fine.

At around 9:30 pm, his can of Red Bull half-finished on the table, Carlos grabbed and hugged his mom, reached for his skateboard and the bottle of tequila and turned for the door. She told him one more time that everything would be OK.

“I love you mama,” Carlos replied, before he headed out into the night. It was the last time Olga saw her son alive.

She peppered her son with calls while he was with his friend. And while Carlos assured her a number of times that he was about to leave, Olga estimates that he finally left his friend’s home at around 12:45 am to make his way home – a route that would take him past the place he was killed.

At the same time, in a bungalow on Bonnie Beach Place, perched on the west side of a shallow canyon overlooking Robert F. Kennedy Elementary School nestled at the bottom, Franco Aguirre listened from his room to slammed doors and raised voices as his housemate, Janet Duarte, and her boyfriend Marcario Valenzuela, were involved in another heated row.

While the two deputies allege to have heard a gunshot prior to Carlos being apprehended, none of the residents in the area I have asked can remember hearing it, though they distinctly remember the multiple shots fired at Carlos.

At around 1:12 am, two LASD deputies were dispatched to Aguirre’s house to investigate a domestic violence complaint – along with two other deputies who, while en route, were flagged down by a pedestrian. The man, Tomas Verduzco, claimed that five minutes prior, he saw a young bald man in his early 20s riding a skateboard with a gun in his hand beside Robert F. Kennedy Elementary School. The man apparently flashed his gun towards Verduzco. When Verduzco was sharing his story, the deputies apparently heard a gunshot in the same vicinity.

According to the Los Angeles district attorney’s report, this is what happened next:

The DA’s report states that Deputies Forlano and Castellanos joined the hunt for the skateboarder with a gun. As soon as the deputies turned from Hazard Avenue onto Almanza Lane on the southwest corner of the elementary school, they encountered Carlos walking toward the car.

As Carlos approached the car, the report states, the deputies saw that he carried in one hand a skateboard and in the other a cellphone. They asked Carlos to stop and to drop his phone and skateboard. He didn’t, and Forlano got out of the car. Ignoring Forlano’s demands at gunpoint, Carlos apparently continued toward the patrol car. Which is when Forlano tried to “get hold” of Carlos’ left arm. Castellanos sprung from the car to assist and grabbed Carlos’ right wrist. Carlos dropped his skateboard on the floor. No mention is made of his cellphone.

The report states that during a “stand-up wrestling match,” Carlos hunched over, at which point Forlano felt the gun in Carlos’ right pocket. But Carlos apparently broke free, and thrust his right hand into his right pocket, his left hand forcing it deeper.

Unable to prevent Carlos from supposedly reaching for his gun, Castellanos pushed Carlos from him as hard as he could, at which point Forlano believed that he saw Carlos begin to pull the gun from his pocket. The report states that, fearing for both his and Castellanos’ safety, Forlano shot at Carlos three times. Carlos continued to run, and Castellanos gave chase. Believing that Carlos was again reaching for his gun, Castellanos shot him a further two times. Carlos collapsed to the floor and was handcuffed.

No gun was found on Carlos where he lay dying. The report says that when the deputies returned to the scene of the original struggle, they found a Bersa model 383-A semi-automatic 380-caliber firearm next to Carlos’ skateboard.

Carlos died of four gunshot wounds, one in the left upper hip and three shots from behind. One of the bullets entered his left lower back and exited his mid chest in a manner that suggests Carlos was falling forward when the bullet struck. He was pronounced dead at 1:57 am.

Aside from containing a number of factual inaccuracies, the district attorney’s report often conflicts with evidence and witness testimony, and throws up more questions than it answers.

• Forlano said that he felt a gun in the right pocket of Carlos’ shorts, and both Forlano and Castellanos report seeing Carlos reach into his right-hand pocket for his gun. But Carlos was left-handed.

• What is more, Carlos’ friends and family describe Carlos as almost always carrying the following in his pockets: two phones, one for music, one for calls; his wallet and keys; and quite frequently a bottle of cologne should he stop to work out in the park.

• Forlano describes having a “stand-up wrestling match” with Carlos prior to Carlos breaking free, while the coroner’s report describes Carlos suffering multiple facial abrasions. But the report fails to describe the severity of the “abrasions.”

Carlos’ father took a video of his son at his funeral. The video shows a hole in Carlos’ forehead the size of a penny, a heavily blackened right eye and what appears to be a broken nose – if not broken, then at the very least severely black and blue. No mention is made as to whether Forlano suffered similar injuries during their “stand-up wrestling match.”

• Castellanos said that while he was chasing Carlos, he saw him “look back at him and reach towards his right pocket.” A video of the actual shooting taken by witnesses contradicts that account. While Carlos is running away, he yells out frightened, “No! No!” Multiple witnesses describe him as simply trying to hold up his shorts. And at no point do the deputies command Carlos to stop.

• The report’s conclusion begins by painting Carlos as being in a state of intoxication, stating that, “Carlos Oliva-Sola and a friend had consumed a bottle of Tequila prior to the incident.” But far from being as intoxicated as the report suggests, the coroner’s report showed that Carlos’ blood-alcohol level was 0.08 percent – only 0.01 percent above the blood-alcohol content threshold for driving in California.

• Tomas Verduzco – the man who apparently saw a skateboarder holding a gun in the vicinity of the school – described seeing a bald man approximately 20 years old, wearing a gray T-shirt. But Carlos wasn’t bald. Carlos had thick black hair. The report fails to mention what color T-shirt Carlos was wearing when shot. (I have been unable to track down Tomas Verduzco.)

• Almanza Street sits in a narrow canyon where noise echoes around the neighborhood. Residents on one side of the canyon even describe being able to hear music from houses on the opposite side. While the two deputies allege to have heard a gunshot prior to Carlos being apprehended, none of the residents in the area I have asked can remember hearing it, though they distinctly remember the multiple shots fired at Carlos.

• What is more, the report details exactly how many times the officers fired their guns: Forlano, three times; Castellanos, twice. The coroner’s report states that particles of gunshot residue are found on both of Carlos’ hands, then concedes that it may have come from being “in an environment of gunshot residue.” The district attorney’s report also mentions that Carlos’ DNA was found on the gun’s trigger. But there’s no mention of how many times the gun, allegedly found next to the skateboard, had been fired, only that it contained five live rounds, one of which was in the chamber – an important point if Carlos was indeed the person who fired the shot allegedly heard by the deputies.

Perhaps most crucial to understanding what happened the morning of September 10 is the testimony of those who saw the events unfold. Multiple witnesses watched the incident from the second floor of a house immediately overlooking the spot where Forlano and Castellanos stopped Carlos, and where the “stand-up wrestling match” allegedly took place.

The family subsequently moved home, and has declined to speak on record about the incident for fear of police harassment before the case goes to trial. But their testimonies were recorded by a private investigator in the aftermath of the shooting, and those recordings reveal that far from being consistent with the deputies’ statements, as the district attorney’s report suggests, they tell a much different story. What is more, the witnesses insist that theirs is the same story given to the police on the day of the shooting.

The witnesses describe an incident spanning three or four minutes that can be whittled down to the following: Carlos had complied with the deputies’ orders, was on his knees before he was pushed to lie face down on the ground then beaten. During the beating, Carlos yelled louder and louder, “I don’t have nothing! I don’t have nothing!” The fear in Carlos’ voice prompted one of the witnesses to intervene, and she shouted at her dog, barking at the commotion, to be quiet. With the deputies briefly distracted, Carlos scrambled to his feet and tried to flee. The deputies didn’t command Carlos to stop and instead, opened fire, one of the stray bullets striking the witnesses’ truck parked in front of their neighbor’s home.

Olga Sola, standing before pictures of her son, Carlos Oliva-Sola. (Photo: Daniel Ross)

Olga Sola, standing before pictures of her son, Carlos Oliva-Sola. (Photo: Daniel Ross)

As family and friends struggle to knit together the fragments of that evening, they circle back over the same seemingly unanswerable questions. Why would Carlos, with no history of ever possessing a firearm, carry a gun with him that night to visit a friend? Why would Carlos, so terrified about going back to jail, stop on his way home to hover around an elementary school and flash a gun at a stranger? Why would Carlos, with his life finally emerging from the shadows, indiscriminately fire a gun into the night – and not even try to flee the scene?

Doubts and self-recriminations have taken their toll. Earlier this year, Olga and Juan’s marriage crumbled, and Juan subsequently moved out of their home. For Jose, one of Carlos’ closest friends, guilt lingers to this day. Carlos had called him not long after 1 am on the morning of the shooting, but Jose was already asleep. When he woke the next day, his phone was bursting with messages, each telling the awful story from the night before.

During the days that followed, Jose turned to drinking to cope, wondering what might have happened had he taken the call. Jose lost his factory job. But when a car wash was organized to raise funds for Carlos’ funeral, Jose volunteered, working tirelessly from dawn to dusk. He impressed Juan with his work ethic – so much so, that Juan found an opening at another restaurant for Jose as a suite runner, like Carlos.

“We were really close, lived really close. If we ever needed anything, we would always turn to each other,” said Jose, baby-faced and clean-shaven. He’s still with his girlfriend, Helen, after roughly three years together.

“He was basically a brother I never had. We had that bond. We finished each other’s sentences, knew what the other was thinking. [Carlos’ death] got to all of us, all our friends, because we know who he was. He was quiet, kept to himself. There’s no reason for him to have a gun – there was no reason for him to watch his back. It’s difficult for everyone because of the way he passed away.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.