Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

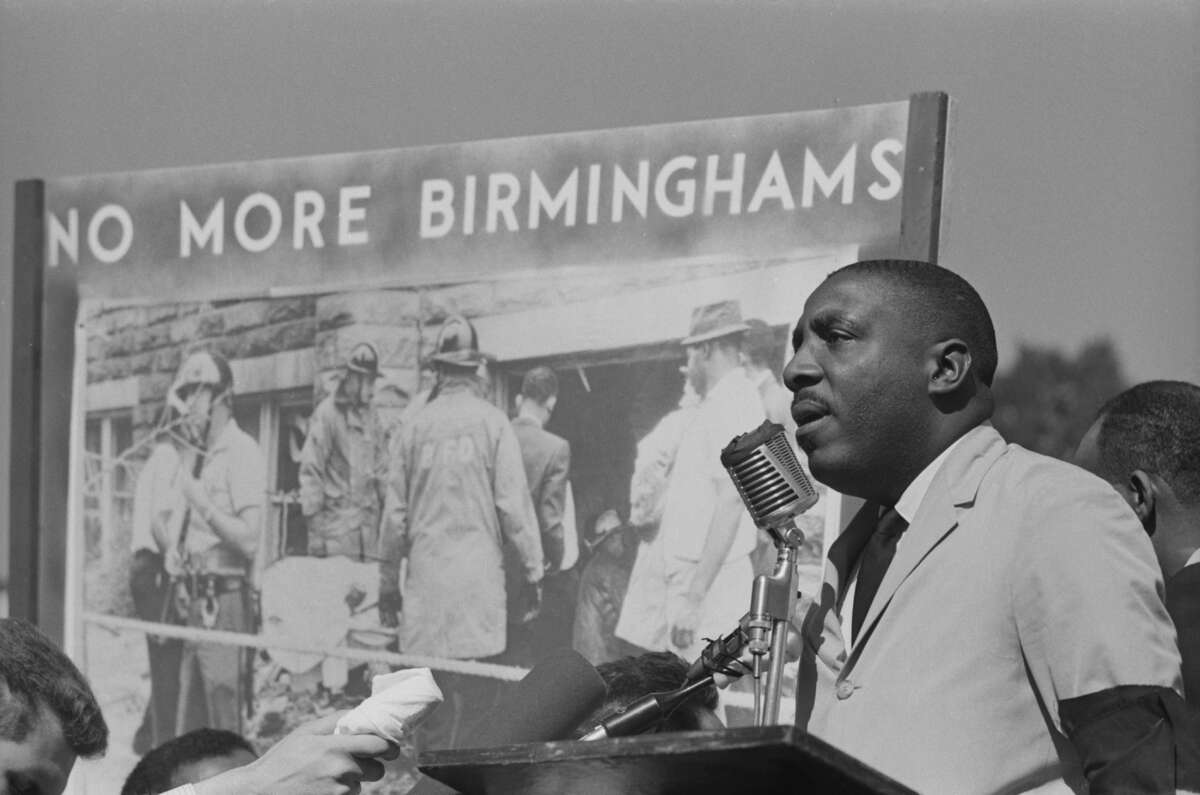

In 1966, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Black mega-celebrity and activist Dick Gregory was sentenced to 90 days in the Thurston County jail in Washington for illegal net fishing.

As a coordinated movement of sit-ins for voting rights and desegregation spread across the South like wildfires, “fish-ins,” an effort for increased native fishing rights, popped up in the Pacific Northwest. Tribes in Washington were protesting state laws that banned forms of fishing other than hook-and-line because it denied fishing rights guaranteed to Native people through an 1854 treaty. The law at the time favored white commercial fishers who were overfishing, threatening the livelihoods of Native people.

The protests caught the attention of the comedian, and he joined Native activists even as the head of the Nisqually Indian Tribal Council in Washington frowned upon his participation, claiming that Gregory was trying to make it a Black issue and a “civil rights matter.” While incarcerated, Gregory participated in a hunger strike, living only on water and bread for nearly 40 days before being hospitalized.

Yet, amid anti-Black sentiment from some, other Native residents appreciated Gregory “co-struggling” with them, says community organizer and scholar Mariame Kaba. Her new short magazine highlights the interconnectedness of struggles among marginalized people and the unparalleled power of Black activism.

She says Gregory’s activism also serves as a model for what multiracial coalitions and movement-building could look like today. As the momentum of the racial solidarity of 2020 has dwindled and new state laws threaten the political power of marginalized communities and the teaching of diverse histories, Kaba says the under-told story of fish-ins is still relevant. Kaba, who’s also the author of We Do This ‘Till We Free Us, hopes to reinvigorate the call for solidarity, particularly among disenfranchised people, through her ‘zine. It shows the expansive nature of civil rights protests, from labor rights to environmental justice and food access.

“There’s been a lot of conversation about Black-centered leadership [since 2020,] but Black struggle has always been involved with working with other people globally to bring about a more just and liberated world for everyone,” explained Kaba, a founder of multiple local and national organizations focused on community education models and ending incarceration.

In an interview with Capital B, Kaba explained that despite anti-Black sentiments, Gregory’s push for another disenfranchised group ultimately led to a significant victory as Indigenous people secured their rights in the “most important legal case in the Native American fishing debate in the past 120 years.”

Capital B sat down with Kaba, one of the country’s leading abolitionist thinkers, to learn more about this historic moment of racial solidarity and how it can be used as an example for Black activists today.

Capital B: What was so special or unique about “fish-ins,” and what does that moment of solidarity tell us about the different ways disenfranchised people can unite?

Mariame Kaba: The first thing was that I had never heard of the fish-in until a few years ago, when I happened to come across an old photograph of Dick Gregory on a fishing boat with a Native American person paddling behind him. And I was like, “Fish-ins? You mean a sit-in on water? What is that?” I’d never heard of it.

I thought it was important because we have been in a moment where people have been talking a lot about Black lives mattering, and us wanting to get solidarity around that part of our struggle, trying to bring people along from different areas, different parts of the world, and different parts of our cultures to struggle alongside Black people. So it struck me immediately that, oh, of course, Dick Gregory would be working in solidarity with native indigenous peoples around a struggle that they were part of. So yes, I think there are lessons for us today.

For me, solidarity is a praxis that is, as Ruthie Wilson Gilmore says, “continuously made and remade.” And it is a praxis that focuses on how our existence and our beings are connected and interconnected. Therefore, it insists that we figure out ways to have reciprocal care and a way to struggle alongside each other, especially when some of us are at risk.

The words ally and allyship have penetrated the culture, and when you think of an ally, you think of somebody who steps into something. But then when that thing is, supposedly, quote, unquote, done, steps back onto the other side of that line where they are back in their own lives.

I haven’t liked that language because it connotes the wrong idea. It gives you a sense that you’re doing something for someone else, rather than in it with other people because we are inextricably linked to each other. So I have always used the word co-struggle, which means you have an investment in this work and see yourself as implicated as co-struggling alongside somebody else.

This reminds me of the unique moment we’re in today, particularly in Chicago, with some Black residents fearful that asylum seekers are taking their resources versus a moment for solidarity building. Were there examples of a need for racial solidarity today that pushed you to publish the zine?

The reason I put the zine out was because I think it’s important for us when we’re in the midst of struggle to always look to what has happened before, not because it’s going to give us the way forward, but rather, it’s going to help us determine what questions to ask while we’re in struggle.

It’s not shocking that we’re in a moment — which we’ll always be — where we are dealing with the tensions of living in a multiracial, multi-everything society. We’re always going to have tensions across our differences, and it’s important to look at a story like this and say, “Yeah, we should be welcoming to people coming from other places, who are displaced.”

As Black folks, we are displaced people. You may feel rooted in this land, but this is not our land. When you see yourself as different, you don’t acknowledge the displacement that we have in common and think to ourselves, “Well, what, how would we want to be treated?”

How do civil, labor, and environmental and food justice, rights intersect?

One thing that [prison industrial complex] abolition has afforded me is a way not to center a particular thing, but to center it all because it’s connected to everything. To have an expansive vision and to see the ways that whatever your struggle is, it connects to other struggles. To make the changes we want to see, we have to change everything else around whatever it is we’re focused on.

I’ve been so heartened over the years now to see, for example, younger people who are interested in climate justice work, talk, and think through abolition because they see the connection between the ways that prisons, for example, sit on toxic land, the way that climate change makes those particular captive populations even more vulnerable. They are seeing the connection between police and policing through “Stop Cop City” and the ways that the cops are razing a forest to create training grounds so that they can better police and surveil the very people who are trying to maintain that forest and are connected to land.

All these things are connected to each other, and I think that Dick Gregory was pushing alongside Native peoples to maintain their fishing rights, which were then meant to keep that environment clean so that they could fish, and so that’s labor and environmental justice. People are able to continue making a living fishing.

He was somebody who pioneered healing and food justice methodology and had a whole thing around nutrition and food and the importance of good food, particularly for Black people, poor people, and people of color to live longer lives, to live healthier lives. I think in this kind of a protest, you see all these different threads of his interests coming together, and I think that that is really critically important as we are fighting now that we figure out where the places of intersection are and where we can pull our resources and pull our power.

Gregory was a public figure who was also deeply involved in social movements. Today, some reject celebrity activism, but what role can high-profile folks play to advance causes?

Dick Gregory was a massive star. He was as famous as Eddie Murphy and Chris Rock put together because of the limited ways people could access entertainment and being the only Black person allowed in so many different spaces. So he is a great example of a celebrity activist.

There’s a lot of divisiveness to celebrity activism today, and that comes from the deep politicization of celebrity to the point where people were just like, well, they’re just in it for money. Plus, our concept of super celebrity is so shrunken that you could be a celebrity for doing literally nothing.

And guess what, a lot of movements need celebrities to do different kinds of things, not to be the spokesperson in the front person, but to give money, to raise money. Because how are we going to pay for all this stuff? This is my pet peeve. I go into this all the time. How are we going to cover the cost of these movements? We don’t have nation-states that back social movements. We are going to need money. And we’re going to need people who can bring attention to issues.

There is never going to be purity; there’s always going to be compromises that are made, and there will be new contradictions that will come up. We have to sit with that and grow up. Gregory is a perfect person as an example of celebrity activism. We should think through the existence of somebody who was like this; what they did and did not do that was good. And we should take those lessons and keep it moving.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.