Part of the Series

Solutions

While a drilling company with an erratic history and cavalier leadership leverages expansion of its onshore operations with ocean drilling by the risky and increasingly notorious method of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, regulators are looking the other way.

The environmental movement went national in 1969 when an oil rig blew up in the Santa Barbara channel and coated the lovely Santa Barbara coastline and the Channel Islands with thick, goopy oil. As the nation watched desperate, oil-soaked birds and sea lions struggling for breath, attitudes began to change toward what we were doing to our national beauty and resources, and Earth Day began. Ironically, while the nation is waking up to the risks of onshore hydraulic fracturing – otherwise known as fracking – for gas and oil on the East coast and in the Midwest, indeterminate fracking is occurring on at least one oil platform in the same picturesque Santa Barbara channel, right next to the Channel Island Marine Reserve and in an area festooned with earthquake faults.

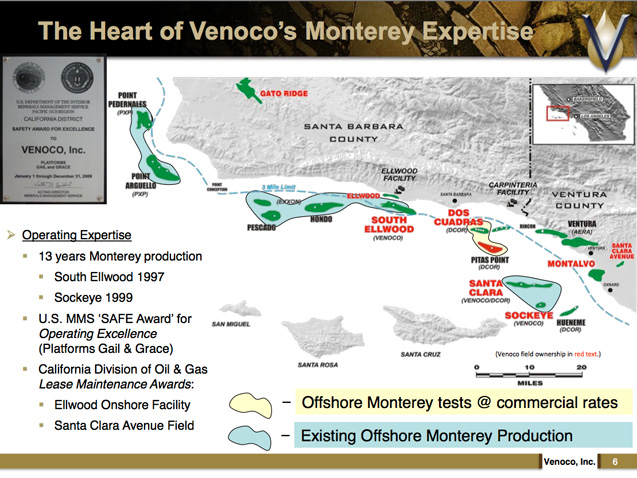

This map – which is a combination of oil company Venesco’s offshore oil fields (named Sockeye and South Ellwood), the delicate federal marine reserves of the Channel Islands, and the web of earthquake faults – shows the fragility of the area that, in at least one or more cases, is being fracked to enhance old oil fields.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a long-used method of extracting natural gas and oil out of spent or difficult gas and oil deposits or out of current wells. It has recently had a resurgence because of new technology and the market push for more US natural gas and oil. Truthout readers are familiar with our work on fracking in the East and Midwest, our coverage of concerns of leaking injection wells where the fracking wastewater is stored and even the problems of injection wells causing rare, moderate earthquakes in areas like Ohio.

Based on information gathered from an obscure 2010 oil prospectus from the oil company Venoco, investigated by the Environmental Defense Center (EDC) and confirmed by the federal government, there was fracking done in 2009 on the Gail oil platform in the Sockeye field in federally controlled waters near Santa Cruz Island in the Channel Islands.

From the EDC web site:

In June 2011, EDC research uncovered that Venoco, Inc., had fracked from an offshore oil platform located in Federal waters in late 2009. Staff with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (BOEMRE), since divided into two separate agencies) confirmed that Venoco conducted its frack job from Platform Gail, located off of the Ventura County coast. According to BOEMRE, Venoco’s fracking operation was allowed under existing authorizations, and no further environmental analysis or public disclosure was made prior to the operation, despite the fact that offshore oil development raises its own host of environmental issues. EDC is unaware of any other specific examples of offshore fracking, either locally or nationally, but is working to determine whether more fracking operations are planned in offshore waters, and to advocate for full environmental analysis and disclosure before any future projects are approved.

In a November 2009 financial disclosure document, Venoco readily admits that they plan to frack the Sockeye field: “Next year, we plan to perform our first hydraulic fractures of our offshore Monterey shale wells at Sockeye,” commented [Chief Executive] Mr. [Tim] Marquez. “We believe one of the Monterey shale zones producing at Sockeye is highly analogous to areas we’ve targeted with our onshore Monterey shale leasing. These wells appear to be ideal candidates for fracturing, but modern fracture technology has never been tested on them.”

In another financial disclosure document there are hints from Venoco’s public filings that the company planned to enhance, through prop fracture (an older method of enhancing older wells) or possibly fracking, their other active offshore oilfield in California state waters, known as South Ellwood, to increase oil production:

The South Ellwood field is approximately seven miles long and is part of a regional east-west trend of similar geologic structures running along the northern flank of the Santa Barbara channel and extending to the Ventura basin. This trend encompasses several fields that, over their respective lifetimes, are each expected to produce over 100 million barrels of oil, according to the California Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources. The Monterey shale formation is the primary oil reservoir in the field, producing sour oil with a gravity of approximately 22 degrees. As of December 31, 2009, there were 15 producing wells and two injection wells in the field.

Injection wells can be used to store wastewater from conventional oil production or fracking. According to EDC attorney Nathan Alley, unlike the federal rules that allow injection wells at the oilfield site, it is not legal in state waters to have injection wells at the site of the oilfield and the wastewater must be removed and disposed of in other areas.

Alley also said it is almost impossible to know if fracking is currently going on within these two oil fields unless you are actually standing on the platform and looking at the equipment on the wells.

The fracking that is occurring on at least one, or possibly two, of Venoco’s offshore oilfields has the potential of several problems, including:

The leakage of wastewater needed for fracking from either the oil well or the injection well where the wastewater is disposed

As with wastewater from fracking onshore oil or natural gas wells, the federal and many state governments have allowed the companies to declare that the contents of the water mixture injected into the well is proprietary to each company, and the governments have given waivers that the contents of the mixture do not have to be disclosed, even to the government. New York State has bucked that trend and required that companies list the ingredients of the water solution injected into the wells. While each company has its own formula, this list includes hundreds of ingredients including carcinogens such as benzene, formaldehyde and kerosene. According to an article in ProPublica on fracking wastewater, “Three company spokesmen and a regulatory official said in separate interviews with ProPublica that as much as 85 percent of the fluids used during hydraulic fracturing is being left underground after wells are drilled in the Marcellus Shale, the massive gas deposit that stretches from New York to Tennessee.”

What wastewater is recovered is then put in injection wells that have a history of leaking and, as confirmed by the federal government, even causing earthquakes.

Very little is known about how these problems may manifest themselves in fracking offshore oil platforms. As the CEO of Venoco wrote in 2009, “These wells appear to be ideal candidates for fracturing, but modern fracture technology has never been tested on them.” In an area with major earthquake faults and sensitive marine reserves, there could be major safety and environmental consequences that are not being monitored by the state and federal governments.

Calls to Venoco and the federal agency the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement were not returned.

When there is leakage of a natural gas well, oil well or a wastewater injection site onshore, it often can be detected in the water table or even on the surface of the ground.

On offshore sites, leakage could go on for long periods of time without detection and be widely dispersed by tides and currents. Without monitoring equipment at the site, there could be a large or slow-moving environmental calamity that could go on undetected until there was serious environmental damage. The Sockeye oil field is right in line with the Channel Island Marine Reserves and could do major injury to the ecosystem. The South Ellwood oil field is right off the coast and could contaminate the Santa Barbara beaches for some time without detection. That area near the Ellwood fields is know for having large natural fractures in the ocean floor, and even Venoco, on their web site, explains that oil has been naturally leaking through the ocean floor for centuries and blames any tarballs on the beach to natural leaking: “Oil seeping into the Channel and onto the beaches is sometimes blamed on oil companies. Yet, history confirms that natural seeps are the cause of this phenomenon.” Any fracking fluids or injection wells of any type would be in danger of coming through the natural fractures already in the rocks.

By now, you are probably thinking that this is a small likelihood because of California’s reputation for being strict on environmental issues, and it would be unlikely that major oil fracking could be going on right in the heart of the California’s biggest oil spill without oversight. Surprisingly, California has been behind in laws and regulations concerning the newest methods of fracking. The state agency responsible for overseeing fracking at first said that very little fracking was going on in the state. They then acknowledged that they really did not know how many oil or gas fracking wells there were in the state, even though it was their responsibility to oversee them. When they finally acknowledged that there were hundreds of wells, they were pressured to come up with regulations. That also has been a long and difficult process. According to a February 2012 report ” California Regulators: See No Fracking, Speak No Fracking,” by the Environmental Working Group:

[Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR)] rationale for proposing new regulations was that “Californians would not want to see injection of fluids associated with oil and gas production migrating beyond the area of where it is intended to be.” The agency did, in fact, receive the extra funds in its 2010-2011 budget, but to date it has issued no fracking regulations. Moreover, in January 2011, Elena Miller, the head of the division at the time, told EWG that it had no plans to do so. A year later, in February 2012, Mark Nechodom, newly appointed director of the Department of Conservation, told EWG and six other environmental organizations following repeated questioning that the agency does not have fracking regulations “on its plate.” He said the department would only begin to develop such regulations if the legislature were to require them or there was “manifest damage and harm” from fracking in California.

The Democrat-controlled California state legislature tried to pass laws on fracking, but the bills were defeated. DOGGR, now under intense pressure from state environmental groups, is just now starting to study what regulations they may require, and it could take up until August 2013 before the state legislature would pass any fracking laws.

A large shale deposit of oil in California called the Monterey Shale has caused a scramble by oil companies to get in on the new area of oil that can be extracted by fracking and other methods. Most of this oil is onshore, so communities and environmental organizations, much like the Eastern communities caught unprepared in the natural-gas-extraction stampede, have been struggling to get some regulations and a modicum of control of the fracking oil-and-gas rush in their communities. Several environmental groups admitted in interviews with Truthout that since the majority of the Monterey Shale wells would be onshore and immediately affecting communities and their environments, there has been little attention paid to the possibility of fracking existing oil wells offshore and the different potential for environmental damage.

So, who is this company Venoco which now controls the two offshore oilfields that have done some past, and possibly current, fracking in the ocean? A very descriptive May 2012 Forbes magazine article outlines a wild history of the management of this company, especially the schemes of its main founder and CEO, Tim Marquez. His management of the company, including suing his founding partner after he was fired while on vacation, shafting Enron in its heyday, taking very large risks with his capital and then buying back enough stock to gain control of the company – along with his ambitious plans to grab as much of the Monterey Shale oil options as possible – could be a plausible whole season plot of the television show “Dallas.”

However, the article outlines that Marquez needs to raise as much money as possible to develop the onshore Monterey wells by maximizing the oil output of his current wells. That is how he got into the oil business: by taking old and sluggish oil wells, increasing their volume, and then buying new oil wells. According to his investor presentation in 2009, the Sockeye and South Ellwood wells were one of the main revenue sources to finance the onshore exploration, and he pitches that he will increase their output to help finance the company’s new growth. Marquez told Oil and Gas Financial Journal that “the whole onshore Monterey Shale play evolved from producing the Monterey offshore and from work we were doing in a part of the Monterey column at our offshore Sockeye field.”

Industry articles on the Monterey Shale are showing that Venoco and other companies haven’t had as much success as they thought with their original exploration of the onshore Monterey Shale sites. According to Venoco financial disclosure documents, Marquez wants to buy back all the rest of the shares of Venoco and take the company private. His stockholders have agreed, and he has until October 5, 2012, to come up with the financing.

However this transaction works out, Venoco is heavily leveraged from buying up onshore Monterey Shale rights and will be pushing its offshore wells to produce as much oil as possible. This pressure for its two onshore wells to produce may push the risk of fracking and other production enhancements to a dangerous level, while both the State of California and the federal government go missing in action when their oversight is needed. With Marquez’s history of high-risk poker with his company, it is time for environmentalists, legislators, state and federal regulators to wake up to the fact that fracking on offshore oil wells is another chancy risk with many unknown consequences. One hopes it will not take another oil disaster – and, possibly, chemical disaster – in the Santa Barbara Channel to get this offshore fracking the attention it needs.

4 Days Left: All gifts to Truthout now matched!

From now until the end of the year, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $44,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just 4 days left to raise $44,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!