Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

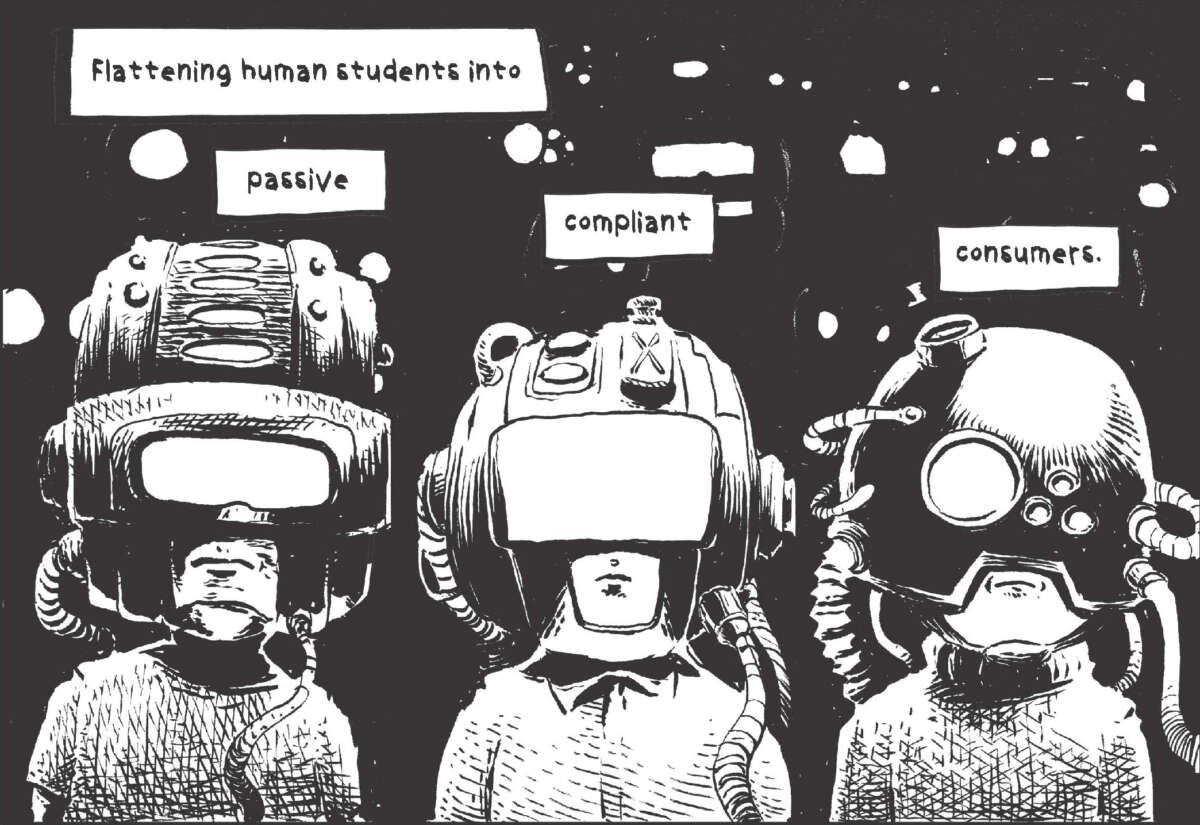

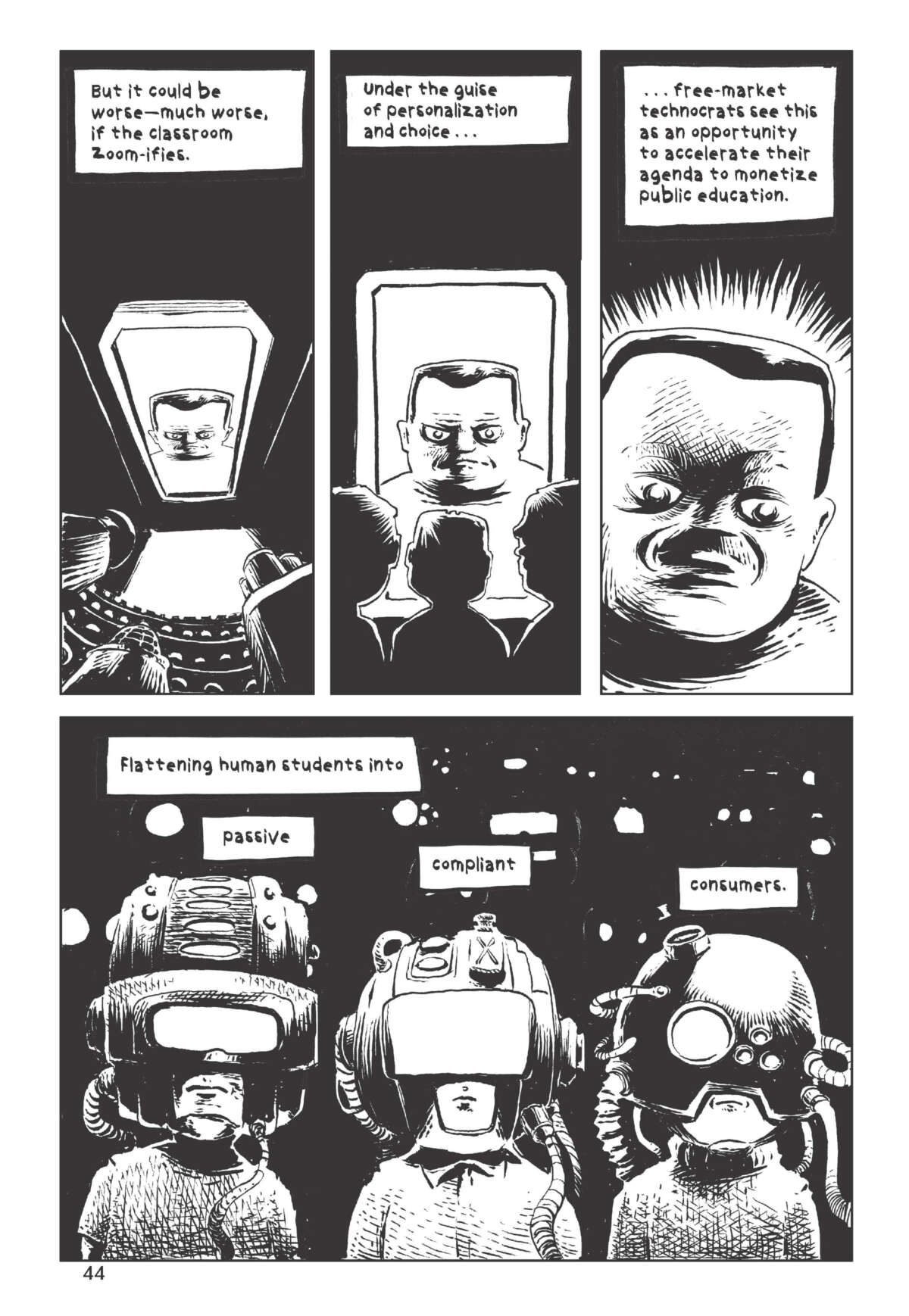

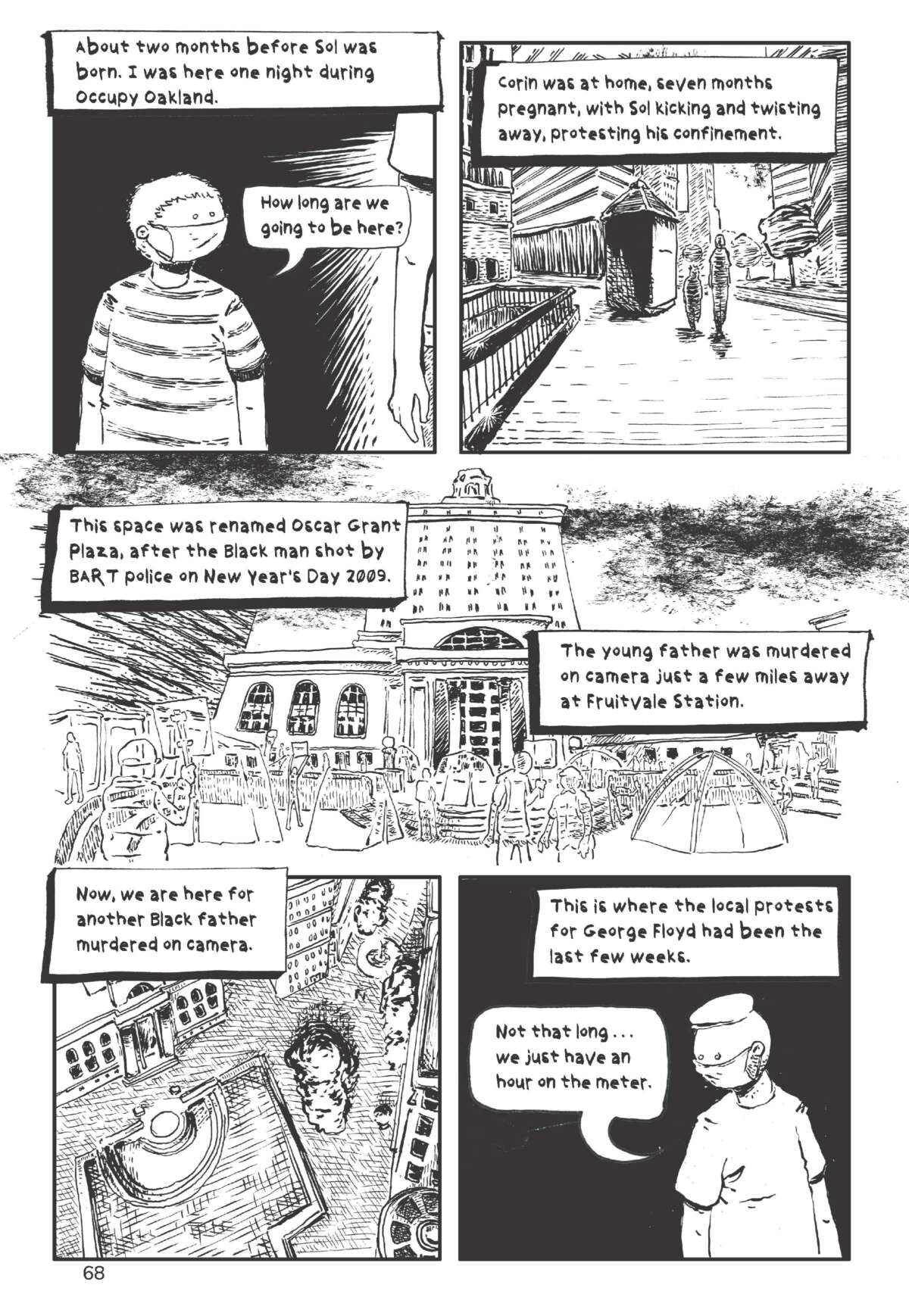

The pandemic changed our lives and society in ways that we continue to grapple with. For teachers, the shifts in their daily lives were nothing short of seismic. In Going Remote: A Teacher’s Journey (The Censored Press and Seven Stories Press, May 16, 2023, Paperback & Kindle), Adam Bessie, a long-time community college English professor in the San Francisco Bay Area, teams up with illustrator Peter Glanting to create a moving and eye-opening graphic account of what it really meant for teachers and students to go virtual.

In this exclusive interview with Truthout, Bessie discusses the challenges of teaching through a pandemic, the complex legacy of the community college system, and how science fiction can help us envision the future of education.

Peter Handel: Your book, Going Remote, is an illustrated memoir of your year of teaching online. As the classroom goes online you begin to learn more about your students’ personal lives and the difficulties they face. What did the experience of teaching online reveal about them?

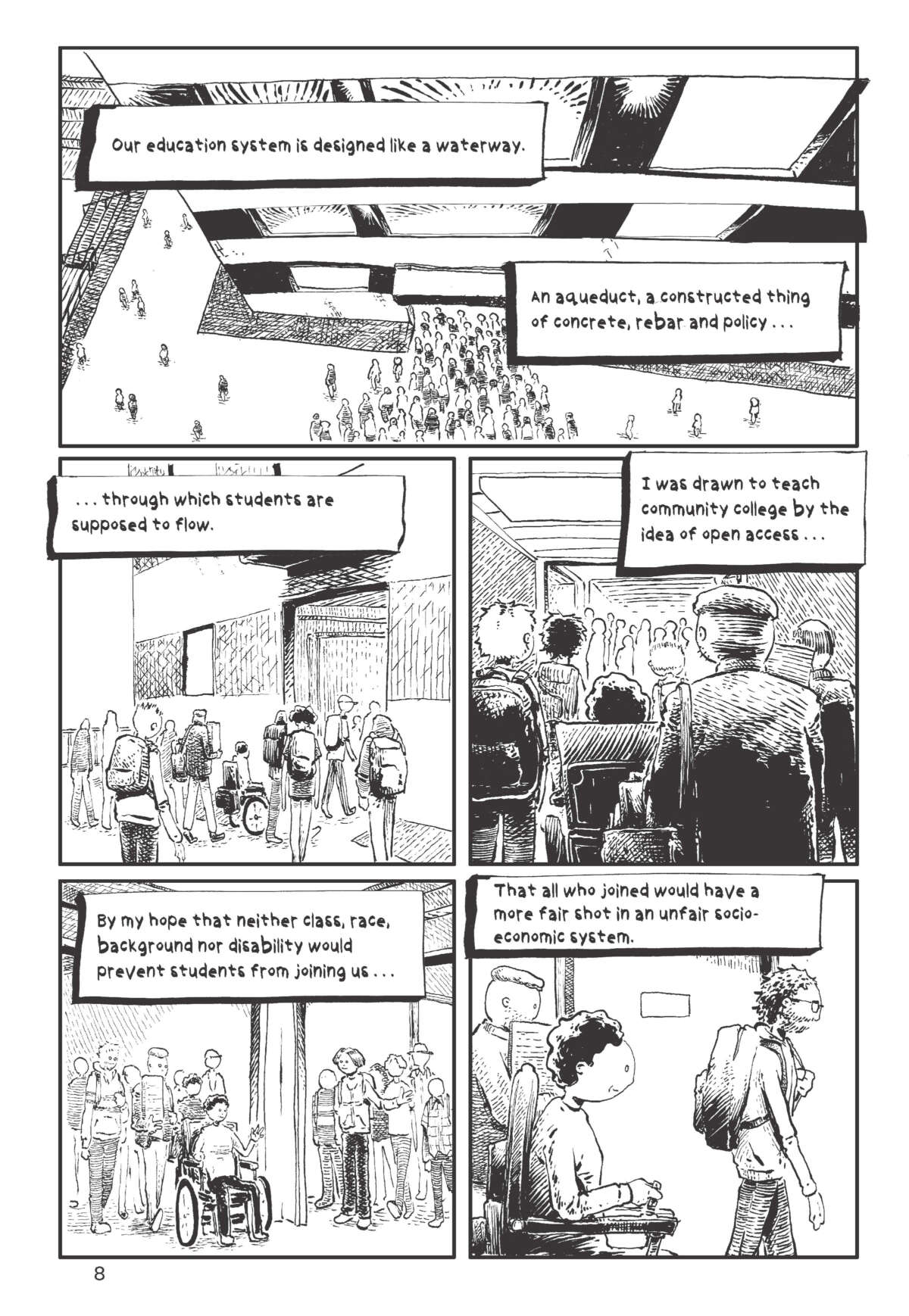

Adam Bessie: I’ve learned over my nearly 20 years of teaching community college English in the San Francisco Bay Area that there is no singular “them” when it comes to our students. Community college students are no monolith, and can’t be reduced to simple stereotypes, such as is in the NBC sitcom “Community.” If you haven’t been to a community college, or don’t know anyone there, it’s hard to grasp the profound diversity of the community college student body in terms of race, class, age, nationality, gender identity, citizenship status, disability, and much more. I can’t think of any other place in American life that draws together such different folks in the same space at the same time. This is the power of community college: it breaks down barriers between folks who are often segregated from one another, and there is this dynamic power from this unique social interaction that crosses these typical borders. This is why I love teaching here.

But most of all, community college is the only point of entry to higher education for many students who have been marginalized and oppressed by American society. And just as these folks were the most impacted by the pandemic, so were they those most likely to hit barriers in school that pushed them out. This has always been the case, but the pandemic — and fully online schooling — meant that even more students dropped out, or worse, didn’t even start college at all, which is reflected in the dramatic drops in enrollment.

Despite these incredible barriers, many students — even those from the most marginalized backgrounds — showed incredible resilience in pursuing their education, while grappling with a pandemic, while adapting to new technology, and doing it all from their bedrooms, closets, garages and workplaces. I’m in awe of the tenacity I witnessed during this period, and it gives me hope for the future of this unique American institution.

You are a longtime community college English professor. You clearly are committed to the mission of offering educational opportunities to all, but you also write that “the community college was born, steeped with the virus of classist and racist contempt.” Talk about that history.

Growing up, I was steeped in a more mythological history of community college through my father. My dad grew up in poverty during the Great Depression, with no real hopes for higher education, and enlisted in the Army, serving in the Korean War. When he returned, he had no money, no real support, and worked multiple jobs, but his local community college welcomed him — and that began a great journey that propelled him to university and a 50-year career as a physical therapist. My dad’s story is much of the reason I decided to teach community college — the idea that anyone could show up and transform their lives.

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, I learned another story — a hidden history of the birth of the community college system. Jennifer Taylor-Mendoza (the current president of the College of San Mateo, a community college in the Bay Area) found “six of the junior college framers were active eugenicists,” and saw the community college or “junior college” system as a means to weed out those of “‘inferior’ genetic traits.” In other words, the system was founded as a means to advantage white folks. As Mendoza concludes, “A community college system established by white males with white supremacist ideologies lends itself to a system plagued with injustice.”

Here is the underlying tension of the community college system: It was originally designed with the express intent to serve neurotypical, middle-class white males and exclude all others, but now serves a population where white folks are the minority. As I ask in Going Remote: Much has changed since the inception of the community college … but is it enough?

In short: No.

You say that your college is a white space, despite the racial diversity of the student body. What do you mean?

Let’s start with me — I’m a white educator, and as my classes are mostly non-white students from a vast variety of racial/ethnic backgrounds, communities and histories, I am the minority in the classroom. Yet, the college has bestowed onto me the power in that room: my name is on the schedule, I can pick the books, I can set the curriculum, I can choose to teach what and how I want to teach, I control the gradebook, I can set the policies. Outside of the choices that I am empowered to make, the very fundamental operating system was designed by white supremacist scholars for people of my race, class and gender identity. Not surprisingly, while white students are in the minority of our student demographics, we are the majority in terms of faculty. Beyond that, state- and federal-level policies regarding community college are also largely decided by white folks surrounded largely by other white folks. Thus, we see a profound demographic disconnect between the demographics of the students and those with the power over their education — myself included.

I do not describe this racial reality out of any sense of guilt, but as a statement of facts that must be acknowledged and addressed. I can — and do — connect with my students of all backgrounds, or at least I try to, and succeed sometimes (and not others). And no doubt, white educators can effectively serve a population that comes from a different background than themselves. But it’s folly to be “colorblind” and ignore this demographic disconnect that favors white instructors. This “colorblindness” harms our student population, who need more educators, counselors, role models, mentors and allies from the communities they are from.

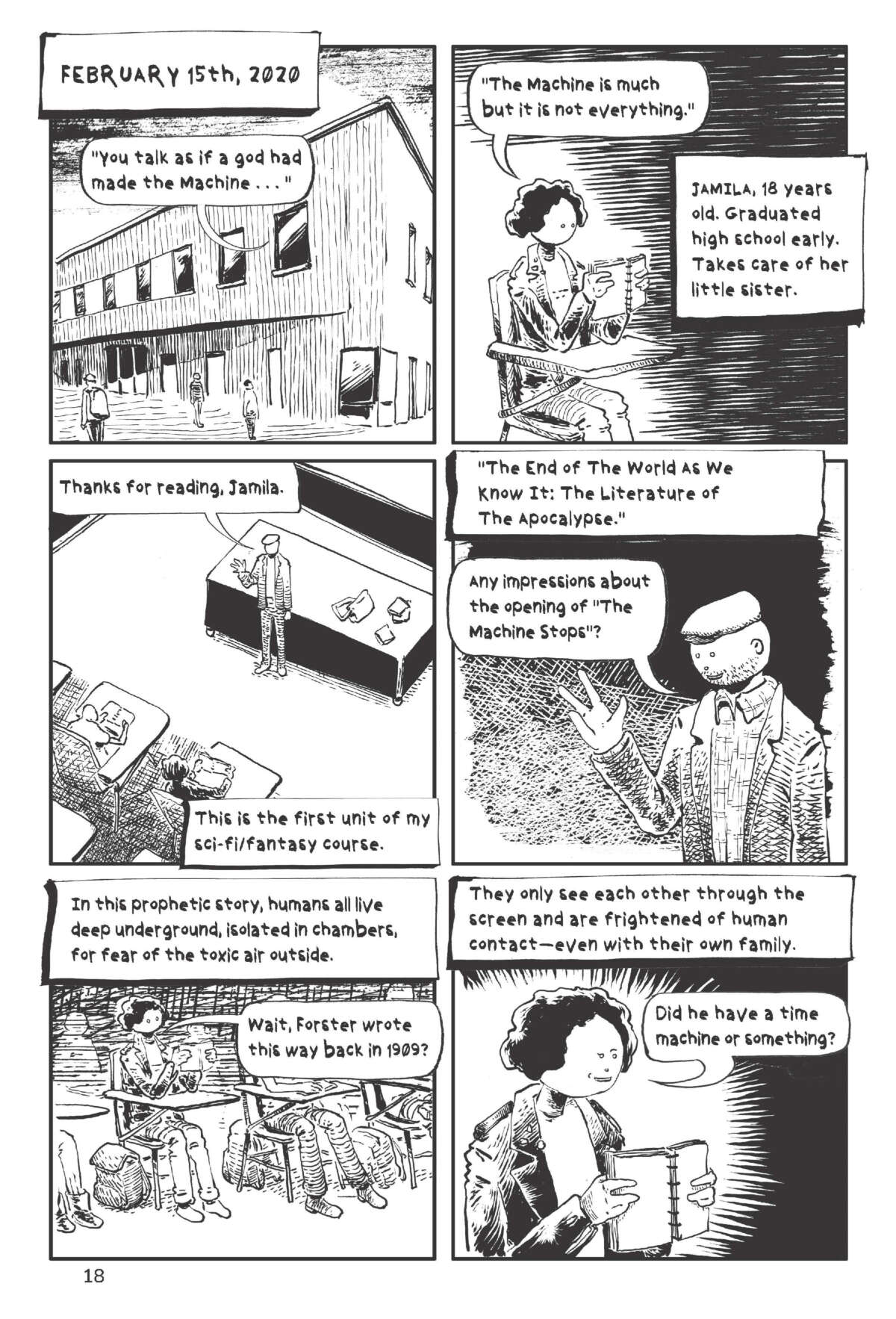

At the time the pandemic hit, you were teaching science fiction novels that suddenly seemed more relevant than ever. Tell us about this.

This true story feels like sci-fi itself! In spring semester 2020, I was teaching a science-fiction fantasy course — and our first unit was “The End of the World as We Know It: The Literature of The Apocalypse.” Our class was reading a 1909 story by E.M. Forster titled “The Machine Stops,” in which everyone lives in undergrown bunkers, isolated from one another, and isolated from the outside, as the air is toxic. Everyone communicates only through TV-like screens. As we all found ourselves on the Zoom tiles, each of us in our own bunkers, I joked that this feels a lot like the story … but no one found it funny. Or at least no one laughed. Or, perhaps, they were all just muted. One student did ask though: “Did you predict this? Is that why you taught this work?”

“No, but maybe Forster did,” I replied.

But for me, sci-fi is not so much about prediction as it is about describing our present reality. I agree with one of my favorite authors, Ursula K. Le Guin: “Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.” In other words, sci-fi is a language that helps us describe our current realities. It’s not just a genre; it’s a way of thinking about the present world, one that encourages critical reflection. Sci-fi is perfect for this moment, one of crisis and thus opportunity: it can provide us creative ways to critique our oppressive systems and imagine better futures. Sci-fi unsettles the status quo, the “normal” way of doing this, the “normal” structures, and helps us to consider how we can redesign our world.

While online teaching and tools are becoming increasingly popular, you say that the power and magic of the real-world classroom cannot be replicated in the virtual world. Why not?

Legendary educator and activist Bob Moses famously claims that students are “the power in the room,” which I’ve had the honor to experience at many points in my career during dynamic classroom conversations. For anyone who has had the honor to be in such a class, you know this exhilarating moment, which feels like an electricity moving through the room. It feels like a jam session, as one student offers a comment, another builds on it, then the teacher leaps in, then another student, and it’s as if the conversation has a life of its own, a harmonic resonance that is part of all the voices, but something more. It’s not just words; it’s the tone of voice, the body language, the whole three-dimensional, full-body live experience that captures the exhilaration of learning.

In my nearly two years of teaching online, I couldn’t figure out how to recreate that electrical current in two dimensions — to find that power. That’s not to say there weren’t beautiful moments of learning online — there were. Also, I have colleagues who love teaching online, and seem able to draw out that power and connection that happens in any great class. But for me, I couldn’t shake that feeling of being remote from students: not seeing their faces or body language, not hearing the buzz and tone of their voices, not feeling that energy in the room that can only happen in community, when we are all in the same place at the same time engaging in a shared pursuit.

Now that we’ve been back to “normal” for a while, what are your thoughts on how the pandemic changed education?

We are not back to “normal” — and this should not be our goal in this so-called “return.” Many students did not return to community college after the flight from campus — enrollments are still down. And for those who did return, many are not on campus, but still fully online. And for those who have come to face-to-face class, it’s a new experience, a hybrid experience, in which the virtual and physical classrooms converge — with both exciting and terrifying visions, especially with the AI era upon us. Most critically, we are seeing what the American Psychological Association describes as a “youth mental health crisis.” We are in a new era — but the community college system has not had the resources and support to transform as it needs to. We need a New Deal for Community College, one that uses this moment of crisis as an opportunity to not just restore what we’ve lost in the pandemic, but restructure colleges to serve the real educational and basic needs of our students.

You became part of a team at your college to help students in crisis during the pandemic. Describe what that was like.

During the pandemic, I received a flood of emails from students in crisis — mental health issues, homelessness, COVID-19, domestic abuse. It was shocking. I felt more like an untrained social worker than an educator. After I sent in such a high volume of reports on students, I was invited to be the faculty representative for the campus CARE team, a crisis response team consisting of counselors, mental health professionals, police services and more. After a staff member files a report on a student in crisis, the team talks through each case at length, attempting to find services and support. After so much time grappling with these emails solo, it was empowering to be with a team and talk through these challenges together, as we sought to help students in need. The CARE team provides a model for the kind of programs and services needed, ones that serve to address the human needs of our community. But it’s not enough: until we have much better socio-economic support and opportunity for the most marginalized and vulnerable, it’s just a set of short-term Band-Aids.

Why did you decide to tell your story in a comic format?

In a way, comics are just like community college itself, with a similar goal — to provide access and engagement! I’ve been writing nonfiction comics for over a decade, with my first professional work of graphic journalism “The Disaster Capitalism Curriculum: The High Price of Education Reform” (with Dan Archer) published here, at Truthout. It’s pretty much all I write now. Comics permit me to express that which is beyond words, to explore complex emotions and abstract systems with concrete visual images and metaphors. Most of all, I love writing comics because they are a truly democratic medium: accessible as a creator and reader, permitting readers to truly identify and personally engage with the magic of paired words and images.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.