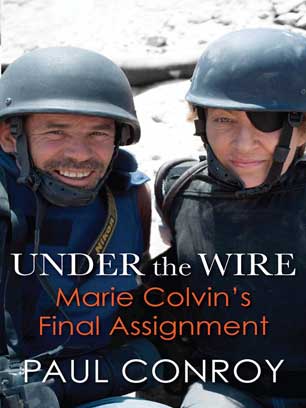

Excerpted with permission from the publisher, Weinstein Books, from Under the Wire: Marie Colvin’s Final Assignment.

Chapter 1: “Paul, I have a plan”

February 8, 2012, Coleford, Devon

Blue cigarette smoke drifted lazily through the shafts of early-morning sunlight. I sat, leaning back in a chair, feet up on the table, drinking my fifth coffee of the morning. I had already lost track of the number of cigarettes I’d smoked and it was only nine o’clock. The phone rang. I inhaled deeply, gulped down a huge mouthful of coffee and picked up my mobile. It was Andrew from the picture desk at the Sunday Times.

“Paul, Marie Colvin is on her way to Lebanon and wants you to meet her there tonight. She’s going into Syria.” He paused. “The no-visa route.”

I told Andrew that I wouldn’t be able to fly to Lebanon until tomorrow. “No problem,” he said before hanging up. The paper’s huge machine immediately swung into action: travel companies began the hunt for tickets and thousands of dollars were wired to airport travel bureaus. Within minutes I received emails with flight details and money orders for bags of cash – all in the time it took to smoke another cigarette.

I was calm. Deep down I could feel the adrenalin dissipating the tension that had been slowly building up inside my body. “At last,” I muttered to myself.

The no-visa route meant an illegal entry to Syria. The al-Assad regime issued few visas to the press and, even if one were granted, it came with the baggage of state security officials, government-organized trips and close monitoring by the intelligence services. War is never just about bombs and bullets: it’s also about media manipulation and propaganda. In short, if you want to get close to the truth, to bear witness, you often have to go “under the wire.”

The Sunday Times had taken weeks to decide which journalist to send to Syria, which was enough time to let the inner tension mount in anticipation of the dangers ahead. There’s always a balancing act that takes place when you’re told you’re being sent to another war zone. Although screaming with relief inside, you have to retain a modicum of calm on the outside: there are loved ones to consider and cartwheeling around the house is generally not viewed as best practice.

My domestic life was complex. I was separated from my wife and living with my new partner, Bonnie, who, having heard most of the previous call, was already in tears. She knew what lay ahead. She had heard the same call when I headed off on assignment to Syria a few weeks earlier with Miles Amoore, one of the newspaper’s rising stars. She knew that once I was inside Syria a deathly silence would fall between us. It was too dangerous to make phone calls or send text messages: editors and journalists were paranoid that simply switching on a mobile or satellite phone gave Syrian security forces the chance to pinpoint your location.

What do you say to someone who knows that you’re heading into one of the most dangerous places on the planet? Even as I spoke, my words of reassurance sounded hollow. They were only words. The television in our living room in Devon was filled with images of bombardment, death and misery as Syrian government troops pulverized the city of Homs with heavy artillery fire. No words could soften the sense of pain and hopelessness that Bonnie must have felt as I walked out of the door early that February morning.

I had been working for the Sunday Times since the beginning of the Libyan uprising the previous year. I think I ended up spending about twenty-two weeks in Libya. I was now going to break the news to my wife, Kate, and my three children that the whole routine was about to begin all over again.

The hour’s drive to my family home gave me time to think. Saying goodbye to the kids was by far the hardest part. Although they had endured it dozens of times before, seeing me off never became any easier for them, or for me. Kate would remain silently furious at my “devil may care” approach to life and her resentment at my departure was born out of seeing her loved one head off to risk life and limb in the knowledge that she might never see him again. She never tried to stop me though. I’d always had her full support. It just got harder for her every time I left. Her fear of my death or injury and the impact that would have on the kids grew with every assignment. I was always the lucky one because I never saw it the same way as the rest of my family. In my mind’s eye, I was always coming back. There was never any doubt.

The atmosphere in Totnes, where Kate and the kids lived, could be cut with a knife. Not only was I now living with Bonnie, but I was about to head off to war again. On the previous assignment only a month or so earlier, rebels from the Free Syrian Army had been forced to evacuate us from Syria on a motorbike. We later learned that government forces were hunting for us. Now I was going back.

My youngest son, Otto, aged ten, told me bluntly, “Dad, it’s going to go wrong this time. I just thought I’d tell you.”

I got the same from Kate. “Paul, you’re pushing it. Your luck’s going to run out soon. You can’t keep doing this,” she told me.

With so much joy in the air, I tried a chirpy old, “Well, I’ll have my bulletproof underpants with me.”

There was not a glimmer of a smile from any of them. My twenty-year-old son, Max, told me that he too had a bad feeling about this one. The only one who didn’t roll the chicken bones in the sand and foresee tragedy was my eighteen-year-old, Kim. He’s also a photographer and perhaps he understood it. Either way, it was like attending my own wake.

During my years in the British army my job as a forward observer wasn’t the most envied. I had been stationed in Germany at the height of the Cold War, a time when the Iron Curtain had well and truly descended and the imminent threat of invasion from the Warsaw Pact countries, spearheaded by Russia, hung ominously in the air. It was my job, along with my battery commander and driver, to let the main Soviet battlefront pass us by as it made its advance into Europe, leaving us behind enemy lines. From this rather unenviable position, we were then supposed to locate targets and pass back grid coordinates of Soviet troop positions to our heavy-artillery units. In reality, we would probably have had a lifespan of about ten minutes, although even that would have been five times longer than the guys who actually manned the guns.

The army and I were never really best of friends. I had a tendency to go AWOL whenever the whim took me, which was more often than not. On reflection, I spent a greater part of my career under arrest of some sort than I did running around and getting dirty. I was trying to get out or “work my ticket,” as it was known, but the powers that were knew this and, to punish me, they kept me in.

In the end, I resorted to planting hashish in my own locker before anonymously tipping off the battery commander with a handwritten note slipped under his door. He promptly had my locker searched and, after much detective work, the soldiers eventually found the hash. I was court-martialed and given nine months in the glasshouse — the military prison at Colchester. On the day I left the prison, I had an interview with the commanding officer of the prison. It was a mere formality.

“What are you going to do when you leave the army then, Conroy?” he asked, clearly bored with the routine.

“Cartwheels, sir,” I answered, with a straight face and no hint of sarcasm.

The commanding officer, without pause, said simply, “Get him out of here, Sergeant Major.”

And that was it. I was now a civilian. I could kill a man with almost any everyday object, I had the ability to make explosives and booby-trap a room, I could identify a Soviet T-72 tank at night and I knew the killing range of most modern weapons. And so it was that I took the next obvious step for a man with these credentials: I became a sound engineer. I spent two years in dark studios. My face went white and my eyes blackened: I developed engineer’s tan, as it’s known.

The years flew by and I crammed in what I could, blanching at the sounds of the words “stability” or “pension.” I lived in caves in Crete, picked tomatoes professionally, rebuilt medieval churches and toured the world with bands, becoming something of a connoisseur of almost every banned substance in the process. But everywhere I went I always took cameras with me – video and stills. I built up a passion for the subjects I shot.

In the late 1990s I ended up in the Balkans, having filmed an aid convoy that was distributing aid to the starving people of Kosovo. The donated aid was a pretty shambolic pile of old tat. For months, the residents of one village looked like they were at a Bay City Rollers convention. I was captivated by what was happening in the Balkans. When the aid convoy left, I stayed on for six months to shoot stills and make a film. The deed was done. I had found my calling and I was once more off into the badlands.

Truthout Q&A with Paul Conroy

Leslie Thatcher: You make a great point of having gotten yourself thrown out of the British military, but it’s clear that your own military knowledge probably saved your life in Syria. How has your military background helped – or hindered – your ability to be an effective photographer/documenter of war zones?

Paul Conroy: Undoubtedly, I would have been dead a long time ago, if it were not for the skills I picked up in the military. I was a Royal Artillery gunner, and as such, had learned to read patterns of fire used by gunners the world over. It’s a language I understand and . . . it gives me the ability to ‘read’ a battlefield and predict what various fire patterns represent. The same can be said of the first aid training that was drilled into me until it was second nature. I did not have to think when it came to fixing up my leg when the rocket punched a hole through it. I reacted without having to think of what to do, my response was second nature.

LT: You describe how you and (Marie) Colvin were concerned about your ability to be objective in your reporting from Homs when you were wholly dependent on the Free Syrian Army (FSA) for logistics and protection. Is there any way war reporters can avoid the issue of “embeddedness” in very hot combat zones? How do linguistic and cultural ignorance amplify that issue?

PC: Both Marie and I were very clear from the outset that, by accepting the help of the Free Syrian Army, we were putting ourselves at an obvious disadvantage. Alas, we had no choice but to accept the offer of assistance, to go in alone would certainly mean our deaths. In these situations, you have to work three or four times harder. You have to check every fact, go to the scene, confirm and reconfirm the stories you have been told. It forces you to up your ante, redouble your efforts to ensure you are getting verified fact and not drip-fed propaganda.

Both Marie and I were very familiar with Arab culture, so that was less of a hurdle for us; of course we don’t know everything but, a quite thorough understanding of Arab civil society and culture goes a long was to assuaging these potential problems. We are always rigorous when picking a translator, they do much more than translate, and a good translator is as important as any of the team. Our translator suffered horrible injuries in the attack that killed Marie. He refused to leave me and, by the end of our escape, we were truly brothers.

LT: Throughout the book – and particularly at the end – you distinguish between “war” and the destruction Assad’s army was wreaking on Homs. By your own definition, would the firebombing of Tokyo or the siege of Falluja count as “war?”

PC: Yes, I was quite adamant that what was happening in Baba Amr was not war; it was the mass murder of civilians, These were not war crimes they were crimes against humanity. Absolutely, the firebombing of Tokyo, the destruction of Dresden were deliberate acts, carried out on civilians, with no strategical advantage to be gained. The sole outcome was the murder and disfigurement of a vast number of noncombatants. This is not war. Again, this is a crime against humanity.

I would question whether siege is a legitimate weapon of war. Having witnessed first hand the siege of Baba Amr, I was transported back to the medieval ages, the brutality and suffering of people caught up in the siege was beyond belief. Again, it is the deaths of civilians that lead me to say it is not war, but a crime against humanity.

© 2013 by Paul Conroy.

For more information, visit https://reflextv.webeden.co.uk/#/under-the-wire/4579247549, https://www.amazon.com/Under-Wire-Marie-Colvins-Assignment/dp/1602862362, https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/under-the-wire-paul-conroy/1115381860?ean=9781602862364.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.