Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

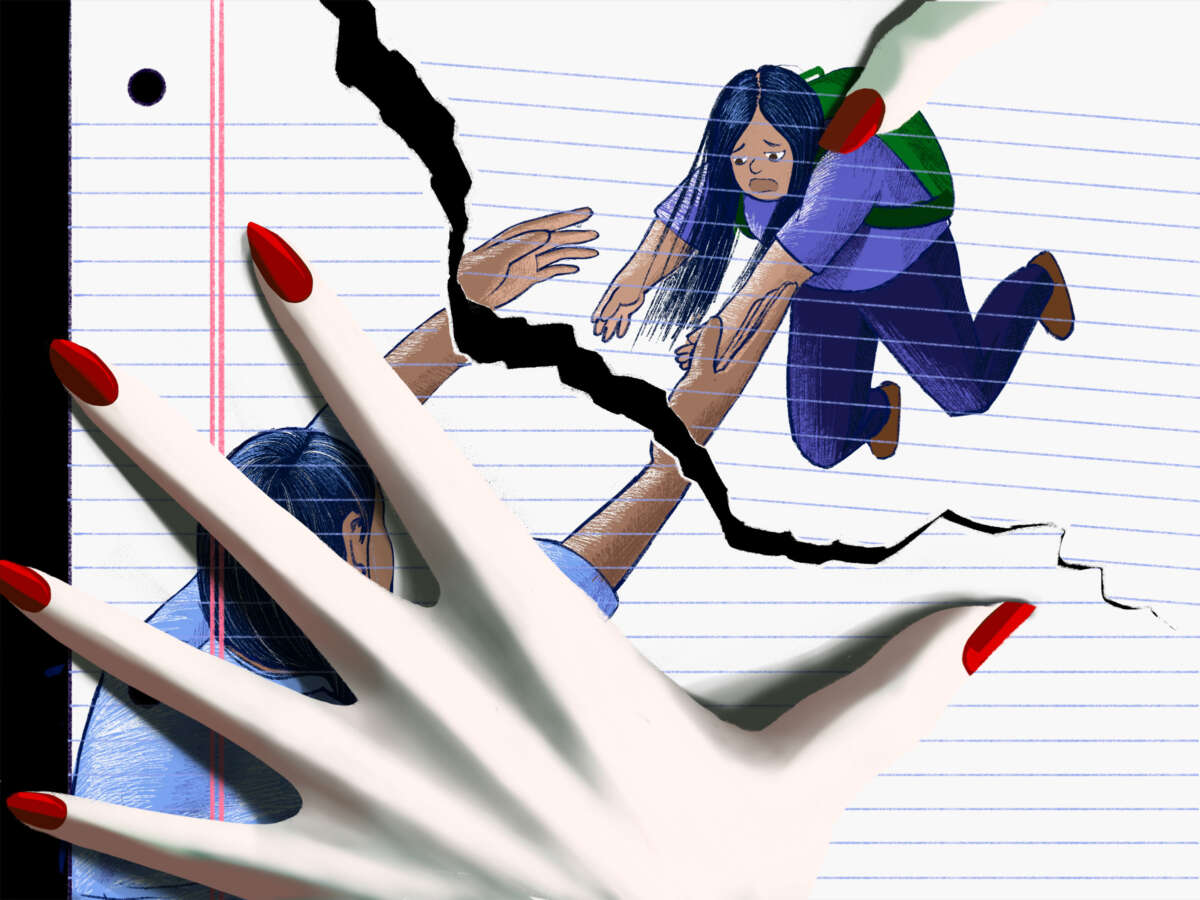

In December 2020, Samantha Hudson arrived with her daughters, ages 2 and 4, at ACCESS Housing family shelter in Adams County, one of the most economically depressed regions in the Denver area. Hudson, who identifies as Native American and has multiple disabilities, hoped staying in the shelter would provide a new beginning and more safety for her girls. What happened next is all too common in marginalized communities throughout the U.S.

Within hours, ACCESS staff called the Child Protective Services (CPS) reporting hotline, and CPS was en route with police to take the children. A couple of weeks later, a petition of drug dependency and neglect was filed against Hudson. It was based on questionable accusations and a past Hudson was working hard to leave behind: substance abuse, intimate partner violence, a minor criminal record and homelessness. Without exploring alternatives, with no drug testing or criminal charges or arrests, and without Spanish-language interpretation for the father, the girls’ parents each entered a “no-fault admittance.” In doing so, without understanding what they were signing, they surrendered their children to the county court without a jury trial.

As a result, Hudson — who is now forcibly separated from two of her children — may never be able to say to her daughters, “I miss my girls every day of my life,” or introduce them to their baby brother. She may never have a chance to explain how hard she tried to protect them from harm and how caseworker bias permanently disrupted their family.

Hudson’s story exemplifies the cruel inequalities weaponized in the name of child protection. On multiple occasions, as evidenced by a range of documents, from meeting records to hearing transcripts, an Adams County caseworker with an extensive reputation for harm circulated alarming accusations of drug use while Hudson was fighting for her right to parent her children. Moreover, this occurred after a long series of oversights allegedly committed by that same caseworker, as well as by other human services staff, regarding Hudson’s case. By the time the accusations were proven false, it was too late to undo the harm to Hudson’s family.

Today, Hudson is part of a growing national movement of prison abolitionists, welfare system professionals, community activists, researchers and affected families working together to challenge the structural oppression enforced by CPS. Family policing systems, these protesters say, are rigged against marginalized people, particularly women of color, with caseworkers wielding vast discretion that is easily abused. As social worker and clinical therapist Martha Wilson points out: “No parent is perfect. Anybody at any moment is capable of doing the wrong thing.”

When Help Is Harm

Bias against poor people of color is foundational to child “protection” in the U.S., which law and sociology scholar Dorothy Roberts has called “family policing” and the “foster-industrial complex.” This form of institutional violence is rooted in the history of separating enslaved families and forcibly removing Indigenous children to residential schools. Wilson describes children removed from families as becoming “nameless and faceless, traceable only by initials and a case number,” hidden behind confidentiality. Meanwhile, families caught up in the system often suffer from attorney negligence and insufficient legal resources.

An abundance of data shows that foster care often increases children’s exposure to harm both in and outside of the home, with 50 percent of foster kids experiencing arrest, conviction or detention by age 17. According to research spanning multiple U.S. cities, after five or more placements, 90 percent are embroiled in the criminal legal system. Foster care is a pipeline to the street, with former foster kids making up 50 percent of the U.S. homeless population.

Homelessness is not just an effect of family separation but also a major cause. Hudson has observed firsthand how widespread an issue it is: “You wouldn’t believe how many people have kids on the streets right now with them.” Many former foster kids lose their own parental rights as adults — and to complicate the matter even more, “parents’ rights” are a key issue constantly undergoing redefinition in legislation proposed across the political spectrum. Wilson explains that once CPS is involved, even parents with housing can easily “become unhoused because of all of the requirements. It’s very hard for folks to maintain their job, especially if they’re court-ordered to go into any kind of rehab. Then there’s no one to pay the rent, and they become unhoused. And then that becomes the reason why the kids get can’t go home.”

Much like police officers, caseworkers hold tremendous power. Once recorded in TRAILS, Colorado’s appropriately named social services tracking system, a claim made by a caseworker — even if it is just an assumption rather than a proven truth — is subsequently repeated as fact and, as a result, very difficult to remove. It can be endlessly cut-and-pasted into file after file and then rehashed in court, even if it contains significant errors — like changes from past to present tense, numerous conflicting accounts, or, as in Hudson’s case, failure to recognize that a parent’s speech is loud because she is hard of hearing.

Yet caseworkers operate relatively free of oversight. From dishonesty during court hearings, to spurious formal complaints stigmatizing colleagues who speak out against injustice, individual abuses of power compound the structural violence. Families in crisis, Wilson explains, meet with constant skepticism, while “foster families are blessed with the benefit of the doubt.”

This form of institutional violence is rooted in the history of separating enslaved families and forcibly removing Indigenous children to residential schools.

Wilson works for the Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel (ORPC), a Colorado alternative that broadens the range of supportive and therapeutic services available, rather than punitive ones. A parent and lifelong community activist, Wilson worked as a child protection caseworker while training as a therapist: “When I recognized how many children weren’t going back home after they were removed, it felt like too big of a clash with my value system. Everything came to a head shortly after the protests [following the murders of] George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor. I just couldn’t be on the wrong side of this fight anymore.”

“A Social Worker Who Did Not Give Up on Me”

In early 2021, Hudson’s lawyer contacted ORPC, and Wilson was assigned to her case. For weeks, Wilson visited area tent cities, leaving her card and offering cigarettes in hopes of finding Hudson, who had taken to wandering in despair.

When they did connect, it was clear Hudson was struggling with the logistics of her treatment plan — therapy, probation, urine analysis, and more — not to mention the powerful temptation of the drugs ubiquitous in the camps. Navigating complicated bus commutes required several hours daily, and Hudson had to travel with all the possessions she could carry, including her basic survival gear. Arriving 15 minutes late could result in a canceled visitation with her girls. Once, Hudson’s lawyer had to file a motion because Hudson was double-booked, with a treatment and a hearing scheduled for the same time. Hudson also had to make a phone call each morning to learn whether she had a random urine test that day. “I had so much going on that there wasn’t even time for me to stop and be,” she told me.

With Wilson’s support, Hudson persevered. By mid-2021 she was stably housed and soon was consistently testing clean. She also “detoxed” from unhealthy relationship patterns, including with the children’s father, adding domestic violence classes to her treatment routine. A month later, she discovered she was pregnant.

The pregnancy reinforced Hudson’s already impressive commitment to her sobriety, but the Adams County caseworker refused to credit her efforts, instead exaggerating every flaw. “I was assigned to a number of clients who had that particular caseworker,” Wilson said. “I was hearing the same thing over and over again: ‘She doesn’t like me. She doesn’t hear me when I talk. She doesn’t treat me like a human.’ Or ‘she’s lying.’”

In February 2022, Hudson learned the Department of Human Services (DHS) was filing to terminate her parental rights despite her exemplary year and a half of progress. She spiraled into a one-day relapse, which, Wilson argues, DHS should have foreseen and prevented. Understanding that relapse is normal in recovery, Wilson took turns with Hudson’s probation officer providing additional daily support. Hudson recommitted to her treatment and preparing for the baby.

Summer 2022 was a minefield for Hudson. In June, the Adams County caseworker, adding to a large pile of oversights she would later have to answer for in court cross-examination, doubled down on submitting misinformation. She incorrectly stated Hudson was missing urinalysis appointments, though Hudson was 99 percent compliant, having missed one appointment for a termination hearing. She also claimed Hudson tested positive for fentanyl, which Hudson, the testing company, Hudson’s probation officer and the county toxicologist all denied.

On July 12, Hudson gave birth to a healthy baby in neighboring Arapahoe County. Mother and infant tested negative for substances, including a definitive umbilical cord test. Yet while Hudson was in labor, a verbal removal order was made. It required no evidence or investigation, and it was made via an ex parte hearing (meaning neither parent was present nor represented). It stated, based on a “potential danger” noted in Hudson’s record years before, the baby would be placed in foster care at 2 days old.

Movement for Family Power has launched a national platform to link organizations devoted to catalyzing mutual aid and abolishing the family regulation system.

By law, the ex parte hearing had to be followed up by a full hearing within 72 hours. So, given Hudson’s vast improvements and several glowing letters written by providers including her probation officer, her team remained hopeful, organizing in-home nursing and other daily support. Wilson vacuumed her vehicle to transport Hudson and the baby. But the follow-up hearing was not scheduled until weeks later, due to mishandling of interpretation for the father (in a state where, as of 2022, 11 percent of households reported speaking Spanish at home). It took several months, but finally Hudson and her baby were reunited full time. In summer 2023, as Hudson lost her appeal in Adams County to parent her girls, she was awarded custody of her baby in Arapahoe County and declared a fit parent, case dismissed.

Looking back over these past few years, Hudson and her supporters say it feels like an attempt was made to crush her. If one or both of these parents had been unambiguously white with stable housing, would there have been false reports of drug use? Why didn’t the negative result from the umbilical cord drug test make a difference? Why were so many mistakes made with Hudson’s case? How did the same facts lead to such different outcomes by county?

Despite these indignities, Hudson is persisting with intense courage and determination. Hudson has been recommended to join a parent advocacy team, and she is participating in a class-action lawsuit and has mobilized a complaint to the Office for Civil Rights. She has testified in the state capitol in support of bills that have since been signed into law, including one that protects low-income tenants by requiring mediation before eviction. Two years sober as of February 5, 2024, Hudson says that, due to her experiences with CPS, “I’m traumatized every day of my life.”

The Movement to Transform CPS

At 8:30 am on a weekday in late 2023, activists filled a Jefferson County, Colorado, courtroom. The protest was one in a series of marches, media appearances, and other actions in support of a parent, Anna, who had not seen her child for almost 1,000 days, instead experiencing countless instances of mishandling and injustice. Like Hudson, Anna has joined in organized political resistance and mutual aid.

The action was organized by the Colorado-based MJCF Coalition, a community organization gaining traction nationally. Members include social workers and therapists like Wilson, as well as parents like Anna and Hudson who have lost children. They speak out against inequities faced by poor BIPOC families at the hands of caseworkers, judges, guardians ad litem (state-appointed child advocates), service providers and even their own attorneys.

MJCF was founded by consultant Maleeka Jihad, who experienced foster care herself — due not to abuse but to poverty, as is most often the case. Every year, she and her family celebrate the anniversary of their reunification, the all too rare best-case scenario.

MJCF provides volunteer-run grassroots resources for networking, healing, advocacy and political strategy. In addition to speaking at legislative sessions and offering community resources, MJCF holds an annual protest to abolish child welfare, during which, in addition to marching and sharing stories and speeches, they feed homeless people.

Wilson explains, “We’re losing a lot of parents to suicide and overdose.… Keeping parents alive is really important to us, keeping them ready and prepared for when their kids come looking, because they always do.”

Abolitionists, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Angela Y. Davis and Mariame Kaba, have long argued that tearing down harmful institutions, or parts of them, is only one side of a multifaceted grassroots process of creating new institutions grounded in safer, healthier, more equitable communities.

Abolitionist organizations throughout the U.S. have different focuses, ranging from harm-reducing reforms for the near term, to permanent abolitionist alternatives. Some raise awareness through media engagement, as Rise magazine does by publishing parents’ stories. Others, like the UpEND Movement and Think of Us, conduct research, redesign existing systems such as youth housing, and mobilize technology to develop alternatives like online community support resources. Many, like JMACforFamilies, engage in parent-led activism by addressing legislative bodies and holding protests.

In 2024, Movement for Family Power has launched a national platform to link organizations devoted to catalyzing mutual aid and abolishing the family regulation system, offering a resource library, a Movement Map activists can add their group to, and holding events online and in person.

Key to abolition is the creation of networks of mutual aid, building community through events and shared resources. MJCF, for example, holds grief therapy groups led by a licensed counselor for parents who have lost parental rights.

During COVID-19 lockdowns, when many child welfare services were paused, poor communities of color throughout the U.S. successfully organized to help one another, giving a glimpse of the better world envisioned by abolitionists in action. In New York City, dozens of mutual aid organizations such as Bed-Stuy Strong and Bronx Mutual Aid Network, some newly formed and others repurposed from existing networks, enabled communities to secure food, child care, mental health support, and more.

Although it was widely predicted that children would suffer more harm without mandatory reporters like teachers watching them, the factual evidence, as shown by the research of Anna Arons, tells an opposite story: Children are safer without the so-called child welfare system. In New York City during spring 2020, as shown by Arons, there was no increase in child abuse and far fewer families were separated, and the numbers did not rise again when services became available. As Roberts says, “We can confidently hope for a society that has no need for family policing, because we are already creating it.”

Note: A change was made to clarify that Maleeka Jihad is not a former caseworker.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.