Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

With rising inequality in the US, and increasing under Donald Trump, there’s a pressing need for a new economic system. Recently, in discussion with sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, Professor Marcello Musto indicated how, “for three decades, neoliberal policies and ideology have been almost uncontested worldwide [and that] almost everywhere around the world, on the occasion of the bicentenary of Marx’s birth, there is a ‘Marx revival.'” Musto argues that “returning to Marx is still indispensable to understanding the logic and dynamics of capitalism.”

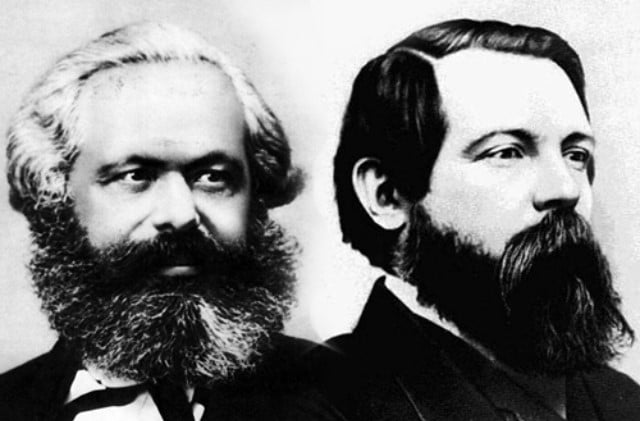

Some of the most famous words in history are the words of Karl Marx: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle.” Marx was a German writer, philosopher and economist. Marx had middle-class roots and possessed an intense interest in economics and political philosophy. He would eventually go on to live in England, and alongside Friedrich Engels, developed some of the most powerful ideas in world history. Together, they shared many correspondences as well as political books and essays, the most famous being The Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Marx offered a critique of capitalism and argued that class structures and the accompanying tensions under the prevailing capitalist order would result in an organized movement of workers to overthrow ruling elites and their draconian forms of worker exploitation. He is considered one of the most influential figures in modern history for advancing revolutionary politics with a practical social science methodology breaking down how the wage system and labor practices had “reduced the family relation to a mere money relation.”

In The Young Karl Marx, a 2017 film co-written with Pascal Bonitzer, director and Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck starts off by portraying a poor 24-year-old Marx in 1842, and shows his first arrest in Cologne, Germany, at his newspaper office while writing for Rheinische Zeitung. This is before he explodes onto the social science scene only six years later and stimulates the intellectual developments of communism in the mid-19th century and forever changes political philosophy and economics.

Peck provides an interesting perspective of this radical and revolutionary mind and illustrates what Marx means to the radical left in terms of the overall discourse. Marx was not some pie-in-the-sky thinker with abstract ideas or fluff. Marx called for an authentic, concrete advocacy of working-class interests, and outlined economic realities and the measures needed to confront the exploitation. In the film, Marx is played by August Diehl. Prior to this film, Peck was nominated for an Oscar for his James Baldwin documentary, I Am Not Your Negro.

The Young Karl Marx also features the young Engels as they chart a shared intellectual path. Engels, the wealthy son of a rich factory owner, is played by Stefan Konarske. He is in love with millworker Mary Burns, who is played by Hannah Steele. Marx and Engels both meet in a café in Cologne in 1844 and Engels appears to be in awe of Marx in some ways, while Marx returns a mutual respect and shows admiration for Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England. Annie Julia Wyman points out that it is through Engels’s urging that Marx supplements his German dialectics and French socialism by studying the English economists.

Featured in the film is Pierre Proudhon, played by Olivier Gourmet, who both Marx and Engels suspect is merely offering a righteous yet oversimplified early version of “can’t we all just get along” without implementing concrete steps in the class struggle. It is Proudhon in the film that authors The Philosophy of Poverty, and Marx answers it with The Poverty of Philosophy. Proudhon might maintain that “property is theft” but Marx maintains that theft is exploitation of the worker. Marx saw Proudhon as simply offering fancy slogans and perpetuating a “petty bourgeois” philosophy.

In the film it is shown that Marx and Engels are repelled by “the Young Hegelians,” a fashionable group of subjective-oriented thinkers for whom they had little respect and patience. This inspired both to pen The Holy Family or Critique of Critical Criticism. According to the Los Angeles Times, “This is the kind of film where we not only hear about the Young Hegelians, we meet some of them verbally jousting with Marx in a newspaper office in 1843 Cologne.” The rivalry continues throughout the film.

Furthermore, Marx sees additional rivals on the European left, perhaps the most notable one being Wilhelm Weitling, played by Alexander Scheer. Marx and Engels see these rivals as mere “intellectual tourists” not willing to clearly state the crux of the matter: the conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The film also features the famed Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, whom Noam Chomsky identified as the person who predicted the 20th century development of East and West command economies, played by Ivan Franek.

The film does an excellent job in capturing the role of Marx’s partner Jenny von Westphalen, a privileged Prussian who was instrumental in the daily survival of the family, along with contributing edits to The Communist Manifesto. She is played by Vicky Krieps, becoming a key radical character that inspires Marx to see the importance of clearly articulating the “vieux monde craquer,” or the “cracking of the old world,” according to Annie Julia Wyman. In the film, we see Marx scrambling from Cologne to Paris to Brussels as a complicated human being: a lover of his wife and children, but unorganized; late with bills; and prone to late nights of excessive smoking, drinking and arguments. Jenny Marx brings the film to life, as well as Marx.

Near the end of the film, Jenny Marx helps to reconfigure an important paragraph, placing it in the correct sequence. The film implies that she catches an error in what preceded “a spectre is haunting Europe, the spectre of Communism.” The Nation points out how “[the film is daring in that] the subject of The Young Karl Marx is not its hero, that the young Marx’s biography is, in the end, secondary to the story of the Manifesto’s shared composition.”

Cicero would like this film. The film gets the viewer to think about how fortunate people are to develop solid friendships. If Marx wasn’t sent into exile by France and never had reached London with Engels, both would never have attempted to join and infiltrate a socialist organization like the League of the Just. They both tried their best to contribute to the League’s intellectual and practical theories, but it culminated with them successfully taking over the club, restoring it to the Communist League and tearing down the League of the Just banner while hanging up their own.

At the end of the film and after the Manifesto is written, it is revealed that later on that same year, European protest and revolution broke out, better known as the 1848 Revolutions. The Young Karl Marx closes with a historical video montage to the music of Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” showcasing key events and influential people of the 20th century.

Dylan wrote in his famous song:

You used to ride on a chrome horse with your diplomat

Who carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat

Ain’t it hard when you discovered that

He really wasn’t where it’s at

And he took from you everything he could steal …

Donald Trump was elected in part by selling a working-class message to a broad base of the electorate that justifiably felt left behind and frustrated with the economic order. With an assist from Paul Ryan, Trump has assembled a brutal cabinet lineup, undoubtedly inserted to undermine anything of potential value in the federal government. The “draining of the swamp” mentality has translated to an overflowing and the already marginalized worker is seeing a further erosion of political and economic rights. It is in this context that the US needs to re-examine the ideas of Karl Marx ever more urgently.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 340 new monthly donors in the next 5 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.