With the American public’s limited attention span for international affairs tied up by fears of ISIS (also known as Daesh), intractable wars in the Middle East and unease about Putin’s Russia, Obama’s much-touted Asia-Pacific pivot frequently gets third or fourth billing on the foreign policy marquee.

The “pivot” (also called the “Indo-Asia-Pacific Rebalance”) is centered on exerting a greater US economic, diplomatic and military influence in the world’s most populous and economically vibrant region.

But on the Korean peninsula, even as the United States bolsters its military posture with more troops, training and weapons, US politicians and the public view the standoff with North Korea without fully knowing or considering important historical realities and potential opportunities.

First, a few facts.

North Korea has been threatened with nuclear weapons at least eight times by six US presidents, including President Obama.

Economically, Northeast Asia is critical to the US economy. China, Japan and South Korea are among the United States’ top seven largest trading partners, with whom the US is trying to turn trade imbalances in its favor. A hallmark of President Obama’s foreign trade efforts in Asia has been the much-disputed free trade agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). In a speech about the Asia-Pacific pivot in 2015, US Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter described the TPP’s passage as being “as important as another aircraft carrier.” Whether intentional or not, Carter’s comparison highlights the overlap between trade and militarism in the rebalance to Asia.

The US has roughly 28,500 troops in South Korea today, with 54,000 more in Okinawa and Japan. With its ally, South Korea (otherwise known as the Republic of Korea or ROK), the US military operates on the premise that it must be “ready to fight tonight.”

And while the Republican Party’s presumptive presidential nominee, Donald Trump, argues South Korea and Japan must “pay their fair share” for the US to keep its soldiers in their countries, The Associated Press recently reported that the four-star Army general overseeing US forces in South Korea said it is cheaper to operate from South Korea than from the United States, because Korea pays half the annual bill ($808 million) and is funding over 90 percent of a new $10.8 billion US base.

It should be noted that independent of what the US spends on its large military presence in South Korea, in 2015, South Korea was ranked the world’s 10th largest military spender (Japan was eighth).

Currently, under a military agreement with the United States, South Korean forces would fall under the command of the US in the event of a war, but a new operational plan to change that is now being considered.

According to a 2015 US Department of Defense report, North Korea (otherwise known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or DPRK) has an estimated 950,000 troops. The Guardian’s North Korea Datablog published a summary of Korean military figures here.

North Korea Threatens a “Sea of Fire”

Given North Korea’s recent history of nuclear tests, rocket launches and threats to turn South Korea into a sea of fire and reduce the US to ashes, it is often dismissed as irrationally hostile, but scholars and foreign policy experts specializing in the region say the country needs to be examined in historical context and with a greater appreciation of how North Korea came into existence.

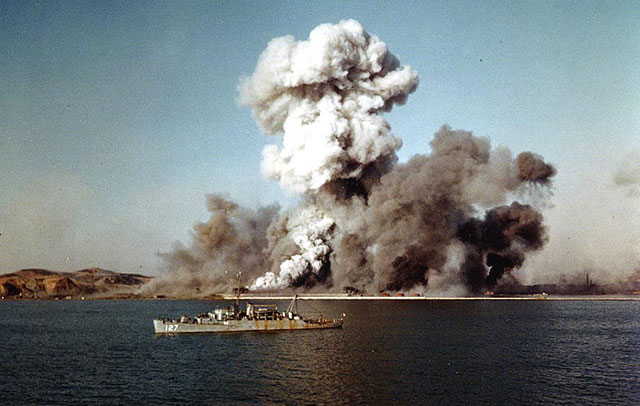

North Korea was founded on the core tenet of juche (self-reliance) three years after US colonels hastily divided Korea along the 38th parallel following the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, and North Koreans suffered extraordinary death and destruction from US carpet bombings during the Korean War (1950-53). By one estimate, Pyongyang was reduced from 500,000 to 50,000 in one year of the Korean War with up to 90 percent (or more) of Pyongyang destroyed by US bombs.

“For South Korea, the US is a security blanket that helps to buffer them against [North Korean] threats.”

Although an armistice brought fighting on the Korean peninsula to a halt, a peace treaty was never signed and North Korea and South Korea remain technically in a state of war. In the subsequent six decades, North Korea has been threatened with nuclear weapons at least eight times by six US presidents, including President Obama, according to Joseph Gerson, director of the Peace and Economic Security Program with the American Friends Service Committee.

And despite a thaw in 2000, when then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright met face to face with Kim Jong-il, relations between the US and North Korea nose dived under President George W. Bush, who branded North Korea as part of an “axis of evil” and called North Korea’s leader a tyrant and a “pygmy.”

In 2006 North Korea detonated its first nuclear explosion and became the world’s eighth declared nuclear state, a milestone North Korea’s foreign ministry attributed to “US nuclear threat, sanctions and pressure.” Today, North Korea is believed to have six to eight nuclear weapons (compared with the United States’ more than 7,200).

Korea analysts say that under Obama’s policy of “strategic patience,” US-North Korean relations are near historic lows. In January 2016, the North conducted a fourth nuclear test (claiming it was a hydrogen bomb), followed by a rocket launch and more fiery threats. Additional UN Security Council sanctions have been imposed but their effectiveness is in question and there’s talk of a fifth nuclear test being imminent.

Meanwhile the US and South Korea regularly practice for war with the North, carrying out large-scale military exercises that include amphibious landings, surgical hits and “decapitation training” to remove Kim Jong-un and other senior leaders. This spring’s war games, reportedly the largest ever, were accompanied by North Korean provocations with each side using the other to justify its own saber rattling.

Gerson and other analysts call the joint exercises harmful and say they should be scaled back or halted to de-escalate tensions. The only way out of this chicken-and-egg cycle of threat-counter threat, Gerson says, is with “disciplined, difficult, patient diplomacy,” something he charges the Obama administration has refused to do.

Continued US Involvement in South Korea

Scott Snyder, senior fellow for Korea studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, said South Korea does have a growing military capability but added, “South Korea is well aware of the risks and consequences of rivalry and transition in Northeast Asia because they’ve been the biggest victims … as the smaller country that is less powerful than Japan or China.”

“For South Korea, the US is a security blanket that helps to buffer them against [North Korean] threats,” Snyder said. But without the US security commitment and absent trust-based relations among neighboring Northeast Asian nations, he finds it hard to imagine security for South Korea.

Snydersees the United States’ security relationships with South Korea (and Japan) as a stabilizing force that has prevented the outbreak of hot conflicts but says the overall situation on the Korean peninsula is moving in the wrong direction. “To be honest, I am probably more pessimistic than I have been in a long time,” he said.

“There are a lot of problems [that] are part of the reason why the US continues to be involved in the region,” Snyder said. This raises the question: Is long-term US military involvement in Northeast Asia part of the solution or part of the problem?

The B-52s

In 2013, calling the move a form of “diplomacy,” the US flew nuclear-capable B-2 bombers and B-52s on flyover missions as a message to North Korea. Similar B-52 flyovers followed the North’s latest nuclear test as a show of strength but Snyder says they offer “diminishing utility.”

“It might have had some utility the first time but increasingly it just looks like part of the usual drill,” said Snyder, warning that nuclear bomber runs are a type of US propaganda that could backfire if North Korean leadership uses the flyovers to reinforce the internal perception that the country is under siege.

“We need to address the situation directly through negotiations that actually have the effect of lowering tensions rather than engaging in propaganda signaling exercises,” Snyder added.

“The contest in Asia is not between North Korea and the United States; it’s between China and the United States.”

Paul Liem, an executive board member of the Korea Policy Institute in California, agrees that US-South Korean war games are counterproductive and breed instability. He says stopping the exercises in exchange for a freeze in North Korea’s nuclear program could pave the way for a peace treaty that would officially end the Korean War, which could in turn eventually lead to normalized relations.

Liem is confident Koreans on both sides of the demilitarized zone dividing North and South Korea would support such steps but added, “I don’t think we’ll do it … the contest in Asia is not between North Korea and the United States; it’s between China and the United States. The North Korean tests play very handily into the perceived need for the US to ramp up its military preparedness in the region.” Liem suggests that much of the increased military activity around the Korean peninsula is, in fact, directed at China more than North Korea.

The Wrong Questions

At the University of Connecticut, Korea and Japan history Prof. Alexis Dudden points out that Korea has been divided as two nations since the dawn of the atomic age. In 2003, during the lead up to the US invasion of Iraq, Dudden says it was absolutely clear to the North Korean leadership that nuclear weapons equal state sovereignty.

“South Korea has always been occupied by the US military so it has not developed its own nuclear weapons system, whereas the North Koreans, having come into being in that historical juncture, determined almost right away — especially building on the experience of the firebombing of Pyongyang — the Korean War was always potentially a nuclear war, not simply because of its timing, but there were discussions of using nuclear materials in that war, on the US side at least,” Dudden said.

Despite the Asia-Pacific pivot, Dudden says the Obama administration’s policy toward Korea has been “willful and absent at best — entirely outsourced to different think tanks and policy interests” and, in her words, “not consistent at all.”

If the US is really interested in helping to bring about “a peaceful and prosperous Northeast Asia,” Dudden said, “we need to ask different questions.” She argues that instead of pursuing a renewed containment theory, creating fearful populations and boosting defense budgets, we should be discussing our common aims such as combating climate change.

Talk Before You Run

Part of the problem with US-North Korean relations, says Daniel Jasper, Asia advocacy coordinator for the American Friends Service Committee, is a dangerous lack of direct engagement that creates bureaucrats and diplomats who lack the linguistic and cultural experience to interact in a positive, meaningful and direct way.

Because diplomats come and go, if they don’t have on-the-ground experience, it’s that much harder to make concrete decisions and anticipate what the other side is thinking, Jasper says.

Before engaging in the most complex issues, like a peace treaty and nuclear negotiations, it’s important to lay the groundwork by cooperating in areas of mutual interest like education, agriculture, health and climate change, according to Jasper. Institutional person-to-person exchanges are essential to building capacity and trust.

He insists the problem is exacerbated by the characterization of North Koreans as irrational, cartoonish and flat-out “insane.” Jasper sees a failure to recognize that tensions spike just before the war games, and says it’s no coincidence that North Korea chose to detonate a nuclear bomb prior to major US-South Korean military exercises.

Dudden agrees that dismissing North Korean leadership as “crazy” is counterproductive and misses the reality that the government is deeply calculating, even if Kim Jong-un has sent very mixed messages about engaging with the United States.

Give Peace a Chance

If a disastrous Northeast Asian war is to be avoided, it will require engagement and diplomacy. Calls for a peace treaty that would formally end the Korean War continued to come from the North even as it prepared to hold its first Workers’ Party Congress in 36 years. South Korea’s Yonhap News Agency reported on North Korean state-run media suggesting Kim Jong-un would not be the first to use nuclear weapons unless “[North Korea’s] sovereignty is violated.” The same report indicated the North was willing to mend relations with “hostile” nations.

Approaching the twilight of the Obama presidency, many questions remain. Will the next US president work to reestablish a dialogue with North Korea? Will the next administration have the ability and patience to engage in tough, long-term negotiations and the flexibility to address complex, decades-old animosity?

In a region clouded with distrust and fear, one thing is clear: Larger war games, more lethal weapons and heightened threats and hostility have proven to be ineffective means to achieve peace and regional stability, which are, after all, what everyone insists they want most.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.