Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Adil Khan has lived as a refugee for much his life. Khan’s family fled Afghanistan in 1980 as the Soviet Union invaded and sparked a bloody war, and he grew up in Pakistan before finally returning to his home country in 2016. Khan studied law and politics at a university in Kabul, but his education was cut short as the Taliban overran the city in August. A member of an organization that opposes traditional practices that encourage violence against women, Khan has met with officials from the former U.S.-backed government and fears the Taliban would accuse him of being a “spy” rather than a member of Afghan civil society. So, he decided to flee.

Khan booked a flight to Pakistan that was soon canceled. The airport in Kabul had become the scene of a frenzied evacuation effort as 20 years of occupation by the United States came to a bloody close. Khan attempted to cross a border checkpoint on foot, where he was beaten by guards and forced to pay bribes. Khan is now in northern Pakistan, having retained his status as a refugee with the United Nations. The Taliban has long operated out of northern Pakistan, and Khan says he is still not safe.

After decades of violence and instability, Afghans already made up one of the largest refugee populations in the world before the recent Taliban takeover caused a mass evacuation in the wake of the U.S.’s withdrawal from its longest-running war. Many evacuated with help from the U.S., which is working to screen and resettle up to 95,000 people within its borders. U.S. officials say they are prioritizing U.S. citizens, Afghans who assisted the U.S. coalition, and others who are vulnerable to the Taliban for resettlement. However, many journalists, human rights activists and members of civil society were left behind and are living in fear of Taliban reprisal, or are currently stranded in neighboring countries and refugee camps across Europe.

“When NATO and USA came to Afghanistan, they told us to support human rights and work for human rights, and I started working for human rights and women’s rights,” Khan said in an interview. “But when they left my country, who will save me?”

An estimated 3.5 million people are internally displaced in Afghanistan after fleeing their homes due to poverty, famine and years of war. More than 2.2 million Afghan refugees are currently living in neighboring countries, such as Pakistan, Iran and Turkmenistan. Since January, nearly 37,000 people have fled across the borders of Afghanistan and applied for international refugee status as fighting between the Taliban and the former U.S-backed government intensified, according to UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency. Another 634,800 people are estimated to have been displaced by conflict inside Afghanistan in 2021 alone.

Huge numbers of Afghan evacuees are also waiting in packed refugee camps across the U.S. and Europe as potential host nations process visa applications. Some 10,000 Afghans are currently living in a crowded tent city at the U.S. Ramstein Air Base in Germany, and another 53,000 are scattered across military bases in the U.S, according to CNN. Others have joined the masses of migrants attempting to enter Europe through countries such as Serbia, where 1.5 million people have passed through since 2015.

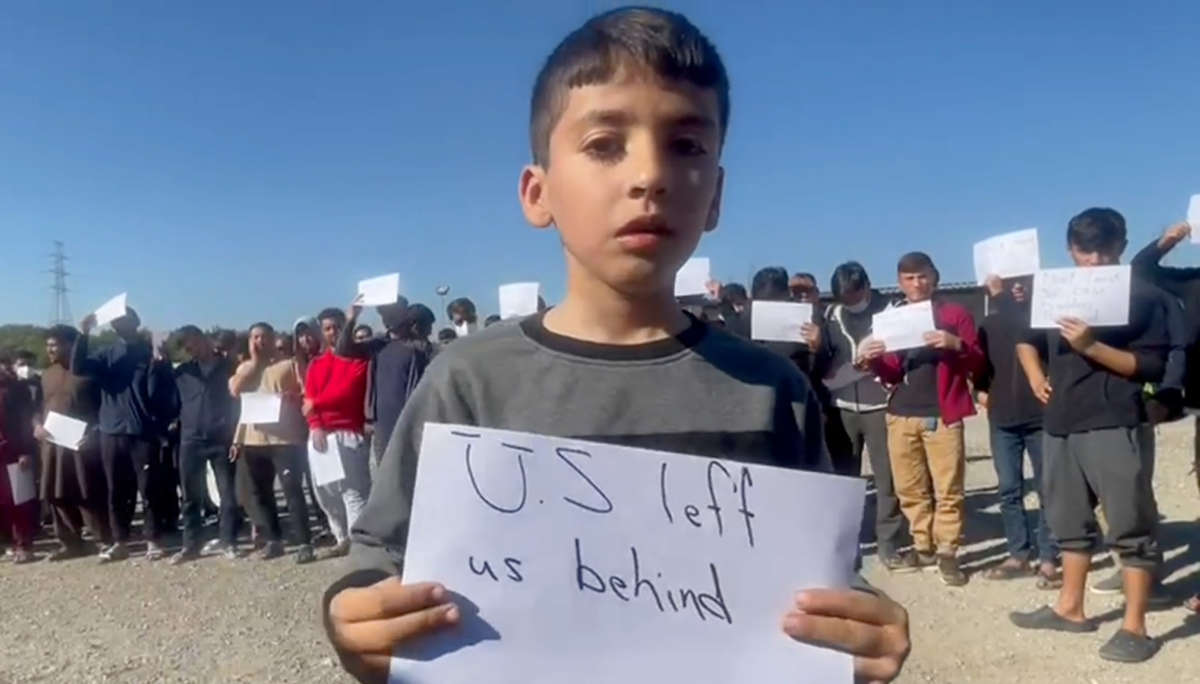

At the Bechtel Enka camp near a U.S. military base in Kosovo, Afghan evacuees released videos of a protest on Tuesday over alleged plans to “forcibly” relocate them or turn them over to United Nations. Up to 2,000 Afghans were airlifted to Kosovo during the evacuation as the U.S. and coalition allies, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, conduct security screenings and process a massive backlog of visa applications. However, about 600 Afghans fear they have been stranded, according to M.E.M, an evacuee and journalist from Kabul who is among them. M.E.M said many are waiting on Special Immigrant Visas that allow Afghans who assisted the U.S. mission to be relocated there, but camp officials told evacuees to accept refuge in any country that offers, including Greece and Turkey, two nations already facing a massive influx of migrants and refugees.

“We want to be relocated to those countries which we worked for, and … our friends and family members and [religious ties] are there,” said M.E.M, who asked to be identified by his initials due to a pending immigration case. “And no, not one of us has been registered with the UN so far, but we have been told to be taken there forcibly.”

Back in Pakistan, Khan said he is running out of money and options. Khan believes his brother was murdered last year by a pro-Taliban gang of Afghans in Turkey, and Khan fears he made himself visible by organizing a protest calling for an investigation at the Turkish consulate in Kabul. Khan said he would go to any country that would accept him to avoid the same fate. However, resettlement is an option for less than 1 percent of refugees globally, and the UN’s resettlement efforts were ground to a halt by the COVID pandemic.

“I need a third country, whatever it is,” Khan said.

Khan said he applied for resettlement with the UNHCR but was told that finding a third country to call home was not an option at this time. Indeed, a website for asylum seekers in Pakistan warns that the UNHCR does not currently have an “active” resettlement program in Pakistan, where 10,800 Afghan refugees have arrived since January 1. UNHCR still operates in Pakistan and the region, but resettlement is reserved for the “most vulnerable” refugees who meet “precise criteria,” according to the agency. Khan said his life is at risk, and he wants a formal interview to be considered.

Chris Boian, a senior communications officer for UNHCR in Washington, D.C, said refugee resettlement efforts have been “severely curtailed” by the pandemic and its restrictions on travel. The United Nations hopes this will change and more governments will increase the number of refugees they are willing to accept. The Biden administration has plans to raise the refugee cap in the U.S. to 125,000, but there are millions of refugees around the world.

“Resettlement is still a solution that only a tiny fraction of the world’s refugees benefit from,” Boian said in an interview. “We estimate that around 1.4 million refugees are in urgent need of resettlement to a third country, and the need for refugee resettlement far outstrips the numbers of places that governments make available for that humanitarian solution.”

Pakistan has not joined the UN’s longstanding convention on refugees and does not have a legal process for protecting those seeking asylum, although the UNHCR says the country generally accepts its refugees. Still, Khan says Pakistan has no interest in permanently integrating Afghans like him, and he fears both remaining there and returning to Afghanistan under the Taliban.

“I need a third country where I can live peacefully,” Khan said.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.