Part of the Series

Voting Wrongs

Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

In key swing states battered by hurricanes, voting rights groups are challenging Republican state leaders over ballot access as elections approach and millions of people contend with ongoing evacuations and recovery.

Civil rights groups filed an emergency lawsuit in a Georgia state court on Monday after the swing state’s Republican governor and attorney general refused to extend the October 7 voter registration deadline by one week for residents who had their lives turned upside down by Hurricane Helene. The case was reportedly moved to a federal district court, where a judge asked for more evidence from the civil rights groups during a hearing on Thursday.

A similar emergency legal motion filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center and other groups on Tuesday asks a federal court to order the reopening of voter registration in Florida as residents prepared to face Hurricane Milton, the second monster hurricane to hit the state in three weeks. A federal judge rejected the motion on Wednesday.

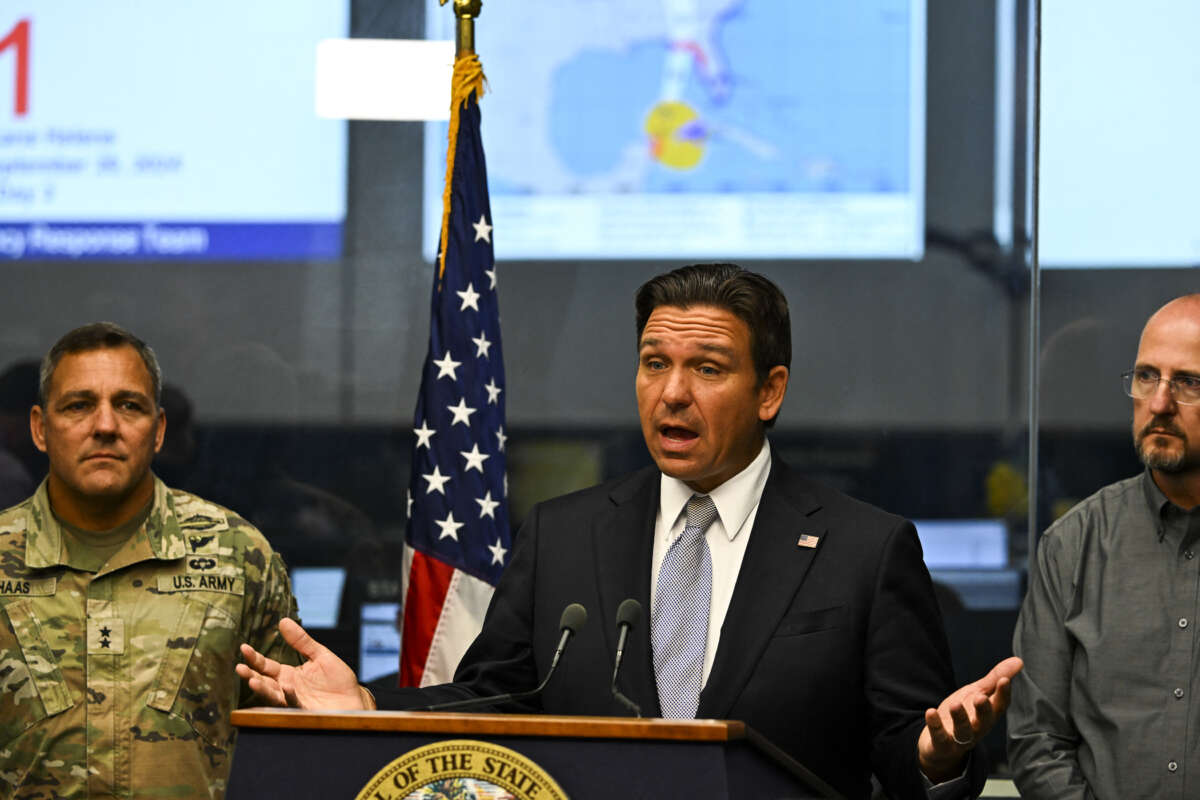

Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis refused a request from a coalition of voting rights groups to extend Florida’s October 7 deadline to October 15 before Milton slammed into the state with deadly force on Wednesday. In Georgia, the October 7 voter registration deadline came and went as residents faced the aftermath of historic flooding. Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp said the levels of damage from Hurricane Helene were “unprecedented.”

Damon Hewitt, president of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, said Hurricane Helene shut down voter registration and post offices in Georgia, which complicated registration efforts with only a month to go before the election. He said people in affected counties need more time to register after a storm that caused tragic deaths, power and internet outages, and devastating floods.

“A natural disaster of this magnitude should not be compounded by a man-made disaster for democracy,” Hewitt said in a statement.

In Florida, DeSantis recently issued an executive order allowing election officials in storm-battered areas to change early polling locations and providing some flexibility to mail-in voters who are under evacuation orders and must send absentee ballots from a different address. However, voting rights groups argue the storms are preventing people from registering in the first place.

“It’s unfair while waiting for a second hurricane in three weeks to hit the state to think people are going to register to vote,” said Larry Hannan, communications director for the pro-democracy group State Voices Florida, in an email. “People were packing up their cars on the west coast of Florida and fleeing, not sure if they would have a home to return to after the hurricane hit.”

Filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Florida NAACP and the Florida League of Women Voters, the complaint against DeSantis argues that “tens of thousands” of Floridians were forced to choose between their own safety and meeting the October 7 registration deadline to exercise their constitutional right to vote.

“Gov. DeSantis has shown little regard for the storm’s impact on voting rights,” said Cecile M. Scoon and Debbie Chandler, co-presidents of the League of Women Voters of Florida, in a joint statement. “While issuing mandatory evacuation orders, he has refused to extend the voter registration deadline, disenfranchising many Floridians who were unable to register due to a disaster beyond their control.”

Hurricane Milton brought deadly and damaging tornados to Florida on Wednesday before the main storm slammed into the state’s central Gulf Coast as a Category 3 storm, bringing 120 mph winds, damaging storm surges and huge amounts of rain. Up to 7.2 million people were under mandatory evacuation orders ahead of the storm, and many chose to flee toward higher ground. Milton left at least four people dead and millions without power in Florida, according to preliminary reports.

Florida has some of the lowest rates of registered eligible voters in the nation as a result of what critics call a “voter suppression machine” created by a various restrictive laws and policies championed by Republicans who embrace baseless conspiracy theories about election fraud.

Brad Ashwell, the Florida state director for voting rights group All Voting is Local, said that even before these hurricanes, DeSantis and his GOP allies have saddled civic groups with unnecessary fines, fees and paperwork requirements to make voter registration drives prohibitively expensive. In an interview, Ashwell said DeSantis’s decision not to extend voter registration “tracks with his record of not wanting people to vote.”

“They’ve just successfully each year made it harder and harder [to register voters] and added these intense fines and penalties, so we’ve seen the registration numbers go down and down in the state,” Ashwell told Truthout.

Civil rights groups lodged similar complaints in Georgia, where a restrictive new voting law and a last-minute push by a Republican majority on the state election board to force poll workers to count votes by hand on Election Day has led to litigation and a looming sense of uncertainty in a swing state that helped to decide the 2020 presidential election despite former President Donald Trump’s attempts to usurp the results.

“The impact Hurricane Helene has on Georgia is still being calculated as my neighbors across south and east Georgia are still burying the dead, without power, mail service and access to their registration office,” said Francys Johnson, a local pastor and chairman of the New Georgia Project, in a statement.

Tamieka Atkins is executive director of ProGeorgia, a nonprofit focused on underserved voters. She pointed to Hurricane Matthew in 2016, when courts in Georgia and North Carolina ordered election officials to extend the voter registration deadline for counties impacted by the storm.

“There’s precedent, and it’s needed,” Atkins said in an interview.

However, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican, held a press conference on Monday and said the state would be prepared for elections despite damage from Helene. At least 40 advocacy groups had signed a letter to Raffensperger and Republican Gov. Brian Kemp requesting a one week registration deadline extension for resident counties impacted by the storm, but Raffensperger did not mention the issue.

That same day, the American Civil Liberties Union, NAACP Legal Defense Fund and Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law filed the lawsuit in state court seeking a temporary restraining order that would force the state to extend the registration deadline to at least October 14. The Republican National Committee and Georgia GOP intervened as defendants in the case.

In neighboring North Carolina, voters can register in person during early voting until November 2, but intense flooding from Helene has destroyed entire communities in the mountainous western side of the state. Election administrators face unprecedented challenges, and the North Carolina State Board of Elections voted on Monday to give extra flexibility to local election officials, especially in areas where roads and communication lines remain disrupted.

“The destruction is unprecedented and this level of uncertainty this close to Election Day is daunting,” Karen Brinson Bell, executive director of the North Carolina State Board of Elections, said in a press conference last week.

Back in Georgia, Atkins said voters and advocates had already been bracing for electoral chaos before Helene tore through a state where poverty rates are high and many people struggle to access adequate housing and health care.

“I think there have been so many significant changes to our elections in Georgia and how they’re administered for years, and so it always feels like we are in a constant state of crisis to be honest,” Atkins said.

Atkins traces the constant state of crisis back to 2016, when the Supreme Court gutted a key section of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that required states with a history of racist voter suppression to clear major changes to elections with the federal government.

After the Supreme Court struck down the so-called “pre-clearance” clause of the Voting Rights Act, Georgia election officials could make sweeping changes without federal oversight. During the 2016 election, Atkins said some voters arrived at polling locations they had gone to for years, only to find handwritten signs directing them elsewhere.

Then in 2018, Georgia made national news because many Black voters were forced to stand for hours in lines that wrapped around their polling stations in order to vote. Other Black voters said they were arbitrarily removed from voter rolls and had to cast provisional ballots. Kemp was running for governor while serving as Georgia’s secretary of state at the time and oversaw an election that he narrowly won.

By the 2020 elections, Georgia was central to the national conversation around the suppression of Black and Brown voters, and grassroots pushback resulted in record turnout that helped flip a red state blue in the presidential race. Two Black poll workers in Georgia faced threats of violence after Trump allies falsely accused them of election fraud.

An outraged Trump notoriously called Raffensperger and demanded the attorney general “find” 11,000 votes to reverse President Joe Biden’s legitimate victory. Raffensperger famously refused Trump’s request but has been broadly supportive of Republican “election integrity” efforts that Atkins and other advocates say will have a chilling effect on voters and complicate election administration, especially after a major natural disaster.

For example, Georgia Republicans passed a sweeping “election integrity” law after Trump’s loss in the 2020 election that added photo ID requirements, tightened deadlines for voting by mail and drastically reduced the number of available drop boxes for collecting absentee ballots. Democrats and voting rights groups have panned the law as a blatant attempt at voter suppression.

Atkins said extra ballot drop boxes would come in especially handy in the aftermath of Helene. However, in 2020, as the use of drop boxes soared in Democratic strongholds such as Atlanta, Trump promoted baseless conspiracies about drop boxes as he contested the election.

However, even Raffensperger opposes the last-minute decision by the pro-Trump majority on the Georgia State Election Board to require that poll workers hand count ballot on Election Days. A statewide hand count would overwhelm local election offices and delay the results for days, providing election deniers plenty of room to spread lies and conspiracy theories like they did in 2020.

“Everything that is happening at election board does matter, it is causing confusion, it is causing a chilling effect, and it has the potential to discourage voter participation,” Atkins said.

Litigation over the last-minute switch to hand counting ballots — rather than counting votes with secure machines — is ongoing.

Meanwhile, Atkins and other advocates are scrambling to reach rural voters who lost power and internet services in three Georgia counties where Raffesnperger said polling locations may need to be relocated due to storm damage. Raffensperger directed voters to check for an online portal for polling location changes, but Atkins stressed that some residents do not have consistent internet service.

Atkins is also warning pro-democracy advocates that their work may not be over after Election Day due to challenges from election deniers.

“Ultimately it is the responsibility of the people we have elected and put into office to ensure that all Georgians have the ability to participate in our democracy, and it doesn’t always feel like that,” Atkins said.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Our fundraising campaign is over, but we fell a bit short and still need your help. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.