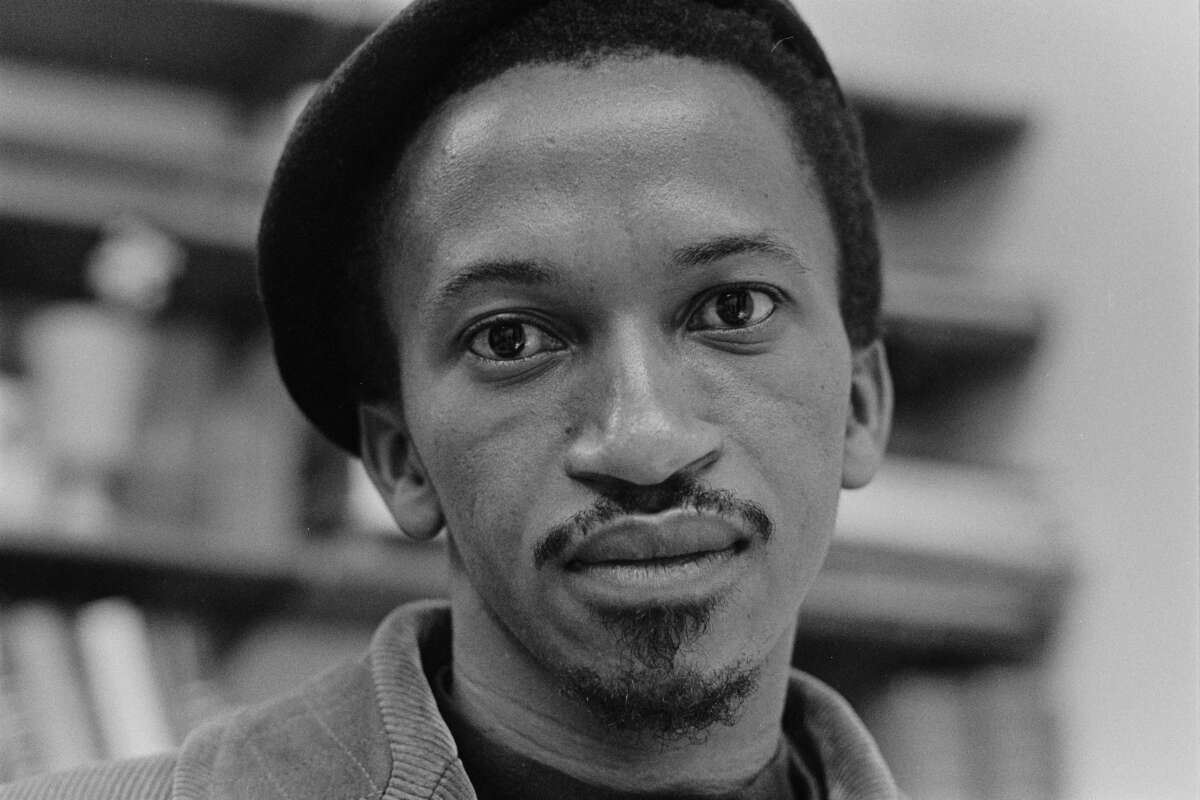

Ernest Cole was one of the most impactful documenters of South African apartheid — and in Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, filmmaker Raoul Peck turns the lens back onto the photographer himself. Cole, the protagonist of Peck’s latest nonfiction film, broke the color barrier by picking up a camera at a time when photography was essentially a whites-only profession under South Africa’s racist regime. Born in 1940 in the Transvaal, Cole challenged the minority-rule government by creating a visceral visual record of the rigorously enforced racial separation policy of the repressive apartheid state.

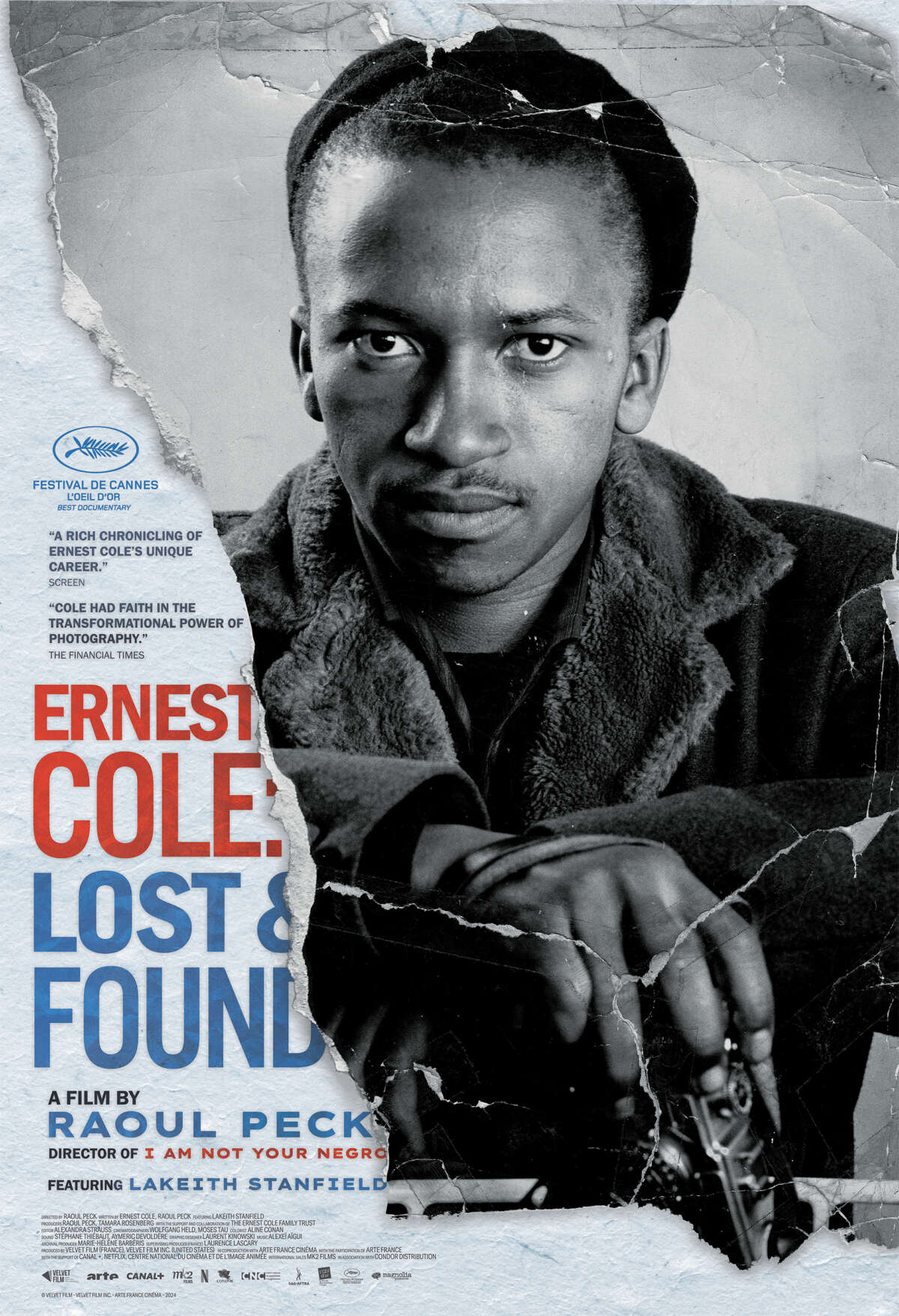

Now Peck has restored Cole to his proper place in the annals of photojournalism with his new documentary. Ernest Cole: Lost and Found is narrated by LaKeith Stanfield, who received a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award nomination for the 2021 Black Panther Party drama, Judas and the Black Messiah, and reads from a text composed by Peck that incorporates words Ernest Cole wrote with testimony from Cole’s family, friends and co-workers.

Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Peck has been making motion pictures since 1982, smoothly switching between nonfiction and fiction films. A versatile director, Peck helmed a 1991 documentary about Patrice Lumumba and then a 2000 feature about the same Congolese independence leader. His 2016 James Baldwin biopic, I Am Not Your Negro, was voiced by Samuel L. Jackson and Oscar-nominated for Best Documentary. His 2017 feature, The Young Karl Marx, dramatized the early years of communism’s founder. Peck’s 2021 anti-colonial HBO miniseries, “Exterminate All the Brutes,” combined documentary and narrative styles.

In this interview, Peck discusses why he decided to make a film about Ernest Cole, how the late photographer’s images exposed the reality of life in apartheid South Africa, the racism he encountered as an exile in America and why Cole’s work remains significant today.

Ed Rampell: How did you encounter Ernest Cole’s photography and decide to make a documentary about him?

Raoul Peck: I was approached by the family. They were in the process of recuperating all of the archives worldwide and reorganizing the estate. They have been trying for many years to make a documentary on Ernest Cole’s story and were never really successful. They tried two different producers. They asked me if I was willing to consider making a film about Ernest. At the time, I was very busy on finishing “Exterminate All the Brutes”; it was not possible.

I continued the dialogue with them. I helped them bring the archive back to South Africa. Then, when I was ready to dig into it again, I thought the project had all the different layers I want in my films and it would be important for today’s generation, and also [those in] my own generation, who have gone through the same period in their political engagement. It’s a homage to all those who — whether in the field, or in exile — fought for the freedom of their countries.

Ernest Cole was a Black South African photographer. What was his significance?

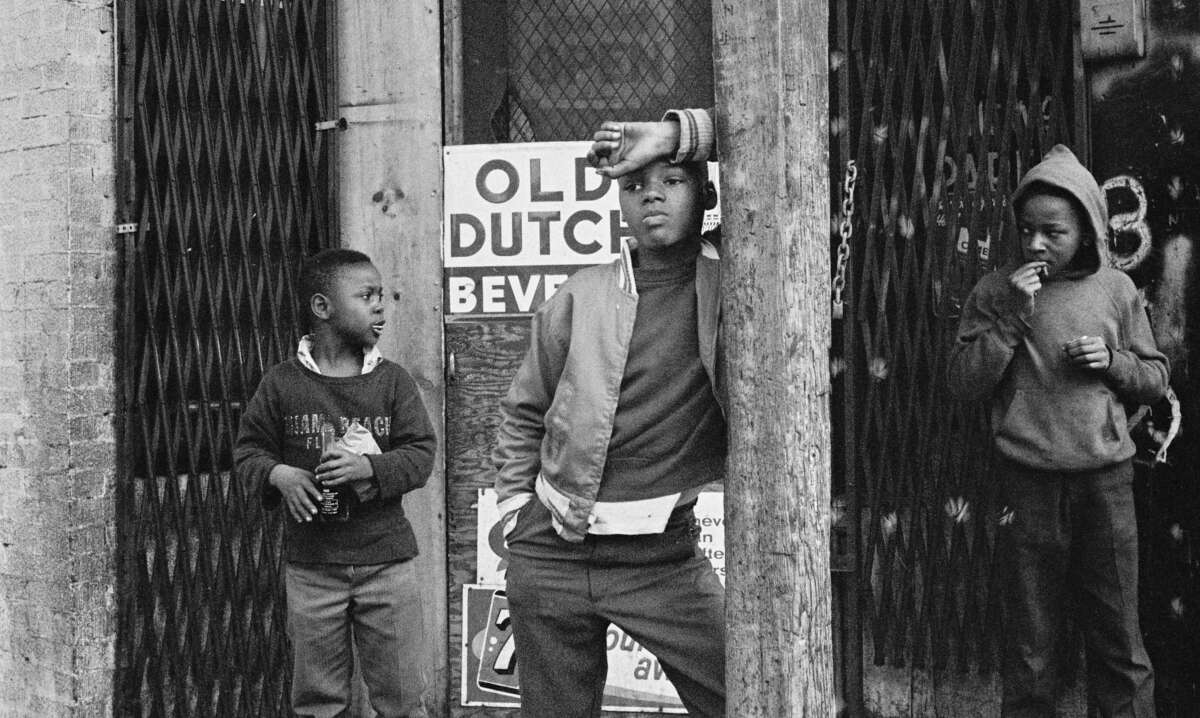

Beyond his talent and the incredible pictures he left us, he was the first to penetrate the belly of the beast. Coming back with incredible images of apartheid. Because there was excessive censorship in South Africa. You couldn’t publish any photos you wanted to; you had to go through censorship. Newspapers, everything was censored.

So, imagine a Black photographer — first of all, a Black photographer in itself was a rarity. They were able to publish some of their work within a certain constraint, or magazines, like Drum, which were authorized but still under censorship. Ernest Cole was the first one to have not only made those pictures, but he made sure they came out of South Africa and were published in the rest of the world.

Why did Cole flee South Africa in 1966? What did he expect to find outside of it?

You’re actually asking me why he left hell? [Laughs] That’s obvious. He realized that the pictures he was making had no future in South Africa. Many innocent pictures couldn’t get published, let alone the kind of destructive testimony he was photographing. He knew he had to go away. Exile is always a very tough decision for anybody. It’s about fleeing — fleeing to survive, to fight.

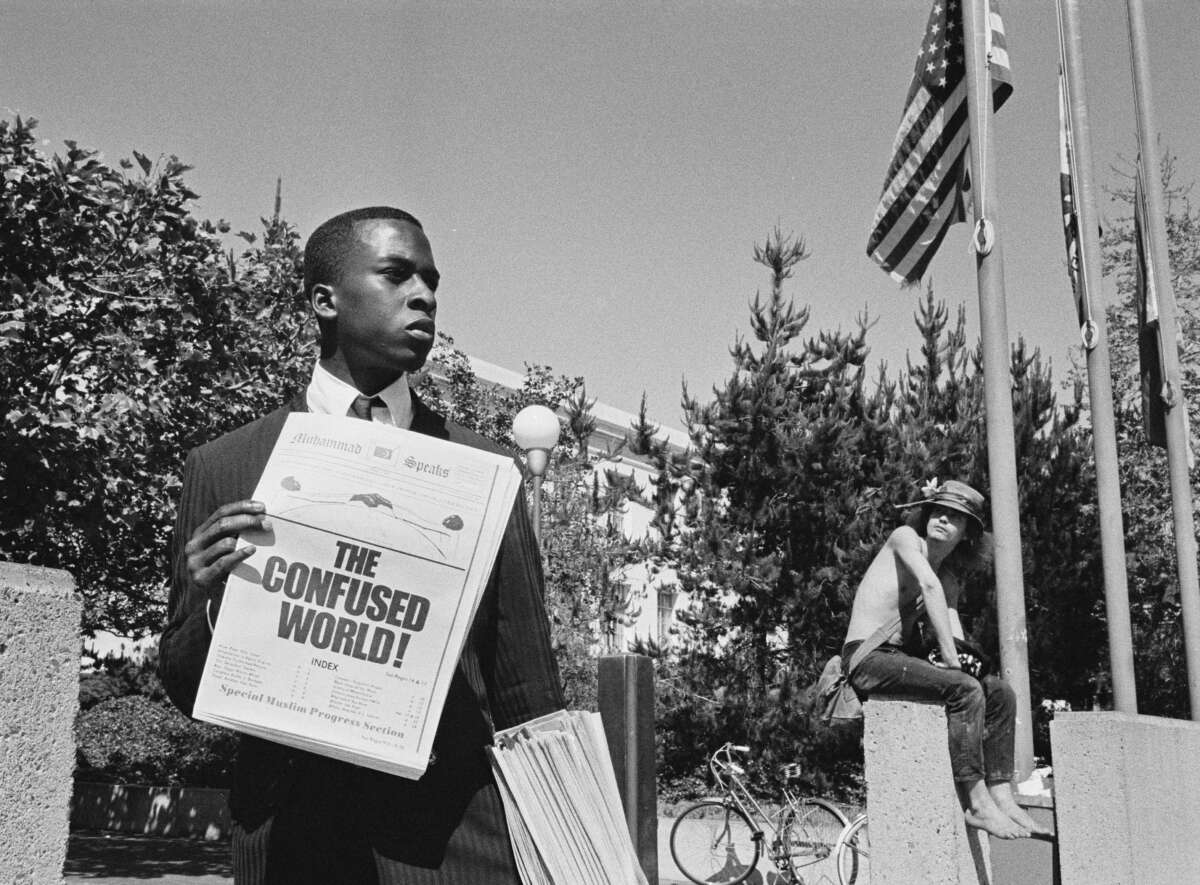

Like everybody else, you think elsewhere is better than the hell you’re going through. But he discovered — I’m not sure he believed the propaganda at the time — that there was a “free world.” There was never a free world anywhere. When he came to the U.S., being 26, a young man at the beginning of his career, I’m sure he had plenty of illusions. But within a few months he already understood where he was.

Cole smuggled his negatives out of South Africa. Combining his text and photographs, Cole’s House of Bondage was published in 1967 in the U.S. According to Aperture magazine: “House of Bondage has been lauded as one of the most significant photobooks of the twentieth century, revealing the horrors of apartheid to the world for the first time.” Almost 60 years later, what is the book’s relevance today, especially given the results of the U.S. election?

First of all, I’d say the book is still important for South Africa today. His analysis at the time, unfortunately, is still partly true. I think he’d turn in his grave to see how little progress happened in some parts of South Africa. In that sense, House of Bondage is still a very credible and impactful testimony.

Concerning what’s happening here in the U.S. … half of America is grieving and we’ll see how to reconnect. My position was, there should always be [something] better than the Republican and Democratic parties. Of course, the election’s outcome is not satisfying for anybody, especially for countries like mine, Haiti, and elsewhere. It’s going to be again an uphill battle and lots of damage throughout the world that will have consequences. The person that’s been elected has not made any secret about his plans.

What are some of Cole’s most haunting images?

It’s difficult to say. Sometimes, the most insignificant photos can have a great impact, depending on the context. That’s what I tried to do in my work — to put his photos into context, not only of his time but of today. It’s the combination of both that creates such an impact.

What did Cole do in the U.S. and what happened to him in “the land of the free”?

You’ll have to watch the movie. It’s much more eloquent than I could tell you. It’s the story that could ultimately finish in a dark place. But history is sometimes strange. The fact that he died basically the same week [as] the liberation of Nelson Mandela. It provides the film a sort of happy ending. You see that his life’s work was not without impact, that it did make sense. That his exile and suffering in exile had a purpose.

In the U.S., Cole wrote “a reality dawned upon me.” Why did he say: “In South Africa, I expected to be arrested. In America, I expected to be killed”?

That was exactly the reality he was confronted with. By the way, many other authors, including James Baldwin, had written about that. Going to the South, he felt like he was in a foreign country. And that the violence was perceptible at every step you take, every look you make. Anything can become violent within a second. Cole was probably very sensitive to that kind of situation.

In terms of “happy endings,” your film takes a sudden turn with a trip to Stockholm. There’s a mystery in your film — how do you suspect 60,000 of his negatives wound up stored in Sweden and what happened to them?

That’s the part I didn’t want to indulge too long in the film. Because, after all, it’s a film about Cole and told by Cole. As he said, he doesn’t care today who hid, who stole, who covered up anything that happened with his work. The essential thing is that his work is back home, in South Africa today. The family trust has, at last, been able to recuperate everything that had been abroad.

I hope Swedish journalists will make an inquiry about that. Two in particular have written about how those negatives were discovered in a bank. Cole went to Sweden and was adopted by the Tiofoto collective of photographers, who made the first big exhibition of his work in Sweden. … He didn’t have a stable place to stay [in the U.S.]. It’s pretty sure Cole brought the negatives with him to Sweden for safekeeping. Now, what happened afterward — Tiofoto ceased to exist. That’s where the inquiry should start. I don’t think the bank is the right place to put negatives in, so obviously somebody wanted to hide them. Or to provide security source to the bloodline, as to where they came from.

Part of your documentary focuses on still images that Cole shot. But as its name implies, movement is essential to motion pictures, to movies. Can you describe your creative process in making Ernest Cole: Lost and Found?

It’s nothing unusual. Chris Marker was able to make a whole movie with 25 photos. It’s not the medium itself, it’s how you use it. It’s a combination not only of photos but also movement on those photos or within those photos. With the text, music, effects — it’s like a symphony you put together. The photos are just one element of the whole film.

Spanning more than 40 years, your impressive oeuvre is wide-ranging, embracing fiction and nonfiction films. How does Ernest Cole: Lost and Found fit into your body of work?

It’s hard to say; the future will say. I don’t look at the films I make as a career plan. They come in a very organic form. Mostly they are a response to the current time I’m living in, wherever I am: Africa, Europe or the U.S. I try to keep them accurate to the current situation of the world. Ernest Cole is a total parallel to some of the stuff we’re experiencing today. In the film we see the story of the South African boycott. How long it took. How politicians were looking for excuses not to boycott the apartheid regime. Because they were making deals with them, exploiting uranium, gold, diamonds. Because also it was a military stronghold for the Western world. Unfortunately, today we see the same kind of situation exists. Why sometimes the same people who talk very loudly about democracy observe massacres and borderline genocide, if not actual genocide, and still finding excuses. In that sense, the films I make are always reminders of what’s going on right now.

What’s next for the prolific Raoul Peck?

I’m not authorized to say but I’m working now.

Can you tell me if it’s a documentary or a feature?

It’s both.

Ernest Cole: Lost and Found was theatrically released in New York on November 22 and in Los Angeles on November 29, with additional cities to follow.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Angry, shocked, overwhelmed? Take action: Support independent media.

We’ve borne witness to a chaotic first few months in Trump’s presidency.

Over the last months, each executive order has delivered shock and bewilderment — a core part of a strategy to make the right-wing turn feel inevitable and overwhelming. But, as organizer Sandra Avalos implored us to remember in Truthout last November, “Together, we are more powerful than Trump.”

Indeed, the Trump administration is pushing through executive orders, but — as we’ve reported at Truthout — many are in legal limbo and face court challenges from unions and civil rights groups. Efforts to quash anti-racist teaching and DEI programs are stalled by education faculty, staff, and students refusing to comply. And communities across the country are coming together to raise the alarm on ICE raids, inform neighbors of their civil rights, and protect each other in moving shows of solidarity.

It will be a long fight ahead. And as nonprofit movement media, Truthout plans to be there documenting and uplifting resistance.

As we undertake this life-sustaining work, we appeal for your support. Please, if you find value in what we do, join our community of sustainers by making a monthly or one-time gift.