Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

In 1892, US Army officer Richard Pratt delivered a speech in which he described his philosophy behind US government-run boarding schools for American Indians. “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” he said. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

From 1879 until the 1960s, more than 100,000 American Indian children were forced to attend boarding schools. Children were forcibly removed or kidnapped from their homes and taken to the schools. Families risked imprisonment if they stood in the way or attempted to take their children back.

Many of the country's 100 schools were still active up until the 1970s. Generations of children were subjected to dehumanization, cruelty and beatings, all intended to strip them of their Native identity and culture. The ultimate goal was to “civilize” the children.

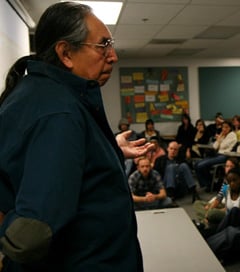

A new documentary, “The Thick Dark Fog,” shines a light on the traumatic boarding school experience through the telling of personal stories. The film focuses on Walter Littlemoon, a Lakota who was forced to attend a federal government boarding school on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in the 1950s. Littlemoon says his culture, language and spirituality were brutally suppressed.

“The government school had tried to force me to forget the Lakota language and I wouldn't do it,” he says in the film. “We had a deep sense of preservation for our culture, so we would go and hide in order to speak Lakota. If we got caught, they were allowed to beat us with whatever they could, but we took that chance. The Lakota language is something that comes from deep inside of you. It comes from how you look at things and how you see things.”

“The Thick Dark Fog” profiles Walter's healing process and attempt to reclaim his heritage. “It wasn't until my sixtieth year that I began to realize that there was more to me. Something was missing. It was like I was a nonbeing,” he says. “I didn't know the medical words of multigenerational trauma or the complex post-traumatic stress disorder, so I called the problem what I felt it to be: the thick dark fog.”

One of the film's more haunting moments provides a montage of excerpts of interviews with Indians describing their boarding school experiences:

“We had all our clothes taken from us.”

“I remember always going to bed hungry.”

“We were being punished, but none of us really knew why.”

“It wasn't punishment. It was beatings. You'd put your hands down and they'd slam the desk down on your hands. They'd take you downstairs and make you kneel down on either a broom handle or a pencil.”

“Soap. That's what she used to wash my mouth. I'll never forget the burning, the choking, the helplessness, the fading out that I went through.”

Will the US government ever come to terms with and acknowledge its dark brutal past? In 1999, the state of Maine, in collaboration with the Wabanaki tribes, set up the Maine Tribal-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“In our society, we gloss over things,” says Denise Alvater, lead organizer of Maine’s Truth & Reconciliation Commission. “We don't do a true reckoning of things that have caused harm and pain and we're not going to allow that to happen this time. This is going to be an actual process of decolonization of our own hearts and our own minds.”

When Alvater was just seven, she and her five siblings were forcibly removed from their home in Maine and put in a foster home where they were tortured, raped, beaten, and starved for four years by a non-tribal family. “I just didn’t know how to cope with life,” she says. “I ended up institutionalized.”

For the past 10 years, Alvater has been telling her story and working with others on the healing and transformation process. In June, Alvater, a member of the Passamaquoddy Tribe, Chiefs of the Wabanaki nations, and Maine Governor Paul LePage signed a Declaration of Intent to create the Truth & Reconciliation Commission.

In 2008, the Canadian Government set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to help indigenous peoples tell their stories and heal. What should the US government do to help indigenous people heal from the abuses they suffered in government-run boarding schools?

Listen to Your Call discuss “The Thick Dark Fog,” accountability and the power of healing.

Listen here:

Guests:

Randy Vasquez is the director of “The Thick Dark Fog.” It debuted earlier this month at the American Indian Film Festival in San Francisco.

Marilyn La Plant St. Germaine is a member of the Blackfeet and Cree tribes from Browning, Montana. She spent the eight grade at the Pierre Boarding School in Pierre, South Dakota, in the 1950s. She says her boarding school experience was bittersweet. She's been a social worker in American Indian communities for over 40 years.

Denise Alvater is a member of the Passamaquoddy Tribe. She is lead organizer of the Maine Tribal-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which is recording the testimony of the Wabanaki Peoples about their boarding school experiences. When Alvater was just seven years old, she and her siblings were forcibly removed from her home and put in an abusive foster home. They were tortured for four years.

Holding Trump accountable for his illegal war on Iran

The devastating American and Israeli attacks have killed hundreds of Iranians, and the death toll continues to rise.

As independent media, what we do next matters a lot. It’s up to us to report the truth, demand accountability, and reckon with the consequences of U.S. militarism at this cataclysmic historical moment.

Trump may be an authoritarian, but he is not entirely invulnerable, nor are the elected officials who have given him pass after pass. We cannot let him believe for a second longer that he can get away with something this wildly illegal or recklessly dangerous without accountability.

We ask for your support as we carry out our media resistance to unchecked militarism. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation to Truthout.