Part of the Series

Struggle and Solidarity: Writing Toward Palestinian Liberation

Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

My dear uncle, Mahmoud Attallah, 63, who was suffering from a lung condition called pulmonary fibrosis, passed away on October 12, 2024, after enduring over a cruel year of genocidal war in Gaza. Due to the ongoing war and bombardment, we were unable to bury him in the cemetery. Instead, he will be laid to rest temporarily in the yard of my grandmother’s house. In these dark days we are unable to grant our loved ones the peace of a permanent resting place. We are forced to find a temporary space for their burial, only to move them later when the situation allows for a permanent farewell.

In Gaza where more than 42,400 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli bombardment in the past year, there is no room to grieve for those who die “naturally” from illness. Natural death during war feels like a luxury — there is no space to mourn loved ones who pass from sickness when collective death and grief overwhelm us in the ongoing genocide. Yet, in truth war hastens all forms of death, not only those directly caused by bombs and guns.

For sick patients in Gaza, living under war conditions is a form of torture. Even those who are not ill often say death would be a mercy compared to enduring the horror of this genocide. But what about those battling illnesses like cancer who need chemotherapy or those who rely on dialysis? How can they survive when health care facilities have been destroyed? Another one of my uncles said he believes Uncle Mahmoud is a martyr because his health deteriorated under the strain of the war. The war worsened his illness and removed any hope for recovery.

Pulmonary fibrosis is a lung disease that causes scarring of the lung tissue, making it difficult to breath. How could my uncle, a lung patient who couldn’t even find the oxygen tubes or the medicine he needed, survive the war? He inhaled the toxic smoke of airstrikes, explosive bombs, phosphorus attacks and asbestos from destroyed buildings. So, did his lung sickness really kill him, or was it the war that claimed his life? As a patient, he witnessed the destruction of his home, the displacement and separation of his loved ones, the daily horror of bombardment and collective starvation — how could these terrible experiences not kill a person? The genocide didn’t just end his life, it shattered his spirit long before his final breath.

As soon as I heard of my uncle’s death, I couldn’t stop thinking about the terrible year he endured while struggling simultaneously with illness and the horror of genocide. My uncle fought to survive with limited access to oxygen tubes and medicine as hospitals were destroyed. In Gaza even natural death from sickness doesn’t feel natural during the war. He lived through the hardest year of his life before he passed. His house was bombed, and he was injured in the leg, forcing him to use a wheelchair as he tried to flee.

While many were displaced to the south, his fragile health left him no choice but to stay in my grandmother’s house, even though it was an unsafe area, constantly under airstrike and bombardment. He attempted to evacuate to Egypt, but he couldn’t cross the borders in the south of Gaza. The border agents turned him back due to his health condition, telling him he could only leave Gaza by an ambulance that he arranged himself. And when he tried to coordinate transport via ambulance, he found it was unavailable due to the high number of sick and injured people in Gaza. He tried once more to evacuate through an Egyptian travel company called Hala, but the Rafah crossing closed, trapping him in Gaza, which has become a concentration camp. Thousands of patients and injured are trapped in Gaza, unable to leave for life-saving treatment due to the closure of the crossing in Rafah.

“My uncle fought to survive with limited access to oxygen tubes and medicine as hospitals were destroyed.”

In his final year, my uncle suffered not just from the war but also from collective starvation, which has gripped Gaza. Living in the north as a sick man, he needed proper nutrition, but instead he withered away, losing weight rapidly. My aunt in Gaza, who managed to visit him, sent me a photo showing how severely health had deteriorated. His body ached from the lack of vegetables and proteins as he survived on an unreliable supply of canned food when they could find it. My mother said he longed for just a piece of tomato or cucumber or even bread, as flour had become a rarity. He faced death not only from illness but also from starvation, destruction and the utter collapse of life as knew it.

Uncle Mahmoud passed away on October 12, and, in that moment, we were struck by the painful contrast of our grief. He died from illness during a 24-hour period when hundreds in Gaza were injured or killed by airstrikes and weapons. As soon as I got the news, I called my mother and uncles and aunts hoping to comfort them over the loss of their beloved brother. Another one of my uncles, Mohammad, was crying on the phone. His voice trembled as he said, “I was hoping to see him one last time, but for an entire year, we could not meet because of the war,” which had torn the family apart by separating those displaced in the south from those who were still in the north.

Uncle Mohammad broke down telling me how Uncle Mahmoud had called him the day before as if sensing the end was near and said, “I love you my brother and don’t know if we will meet again with this war going on.” He said Uncle Mahmoud ended the call saying: “We are humiliated here, displaced, living in tents. Pray for us.”

My mother was also crying when we spoke. It was a deep loss, as she had been hoping for one last reunion with her brother. Now she can’t even see him at his funeral. What a cruel reality Palestinians in Gaza are living in. They are in the same city, but they can’t attend the funeral of their loved ones. They can’t even bury them. It feels like a luxury to talk about such things when in Gaza people are forced to dig a collective grave, desperately trying to find a piece of land in which to bury those killed in airstrike.

We are not even allowed the simple act of grieving for a family member who died from illness. We are already living with constant trauma of fearing our family members’ death in the war, and when the moment of loss finally comes, our most basic human need — to grieve and say goodbye at their funeral — is denied to us. For over a year now, everyone in Gaza has been living in a constant state of trauma, unable to grieve amid the devastation and ongoing massacres and bombardment.

I can’t help but think about how different the conditions of life in Gaza are from where I live now in the U.K. I once attended the funeral of an English friend’s son, and it was a peaceful, beautiful ceremony. There were flowers, heartfelt speeches about his life, his favourite music and the sharing of cherished memories. It was a time for his loved ones to come together, tell stories and celebrate his life. Afterward, they gathered for food and music, creating a space to mourn and to remember.

But as Palestinians, don’t we deserve the same right to say goodbye to those we love? Why couldn’t my uncle see his brother one last time, even though they were in the same city? Why couldn’t we go and attend the funeral or even talk about his death as though it were normal? There are no “normal” deaths occurring during this war. Everything we once took for granted — like burying our dead and grieving together — has been stolen from us.

I want to take this moment in this space to grieve my dear Uncle Mahmoud and to remember him — to share my memories, my relationship and to finally say goodbye.

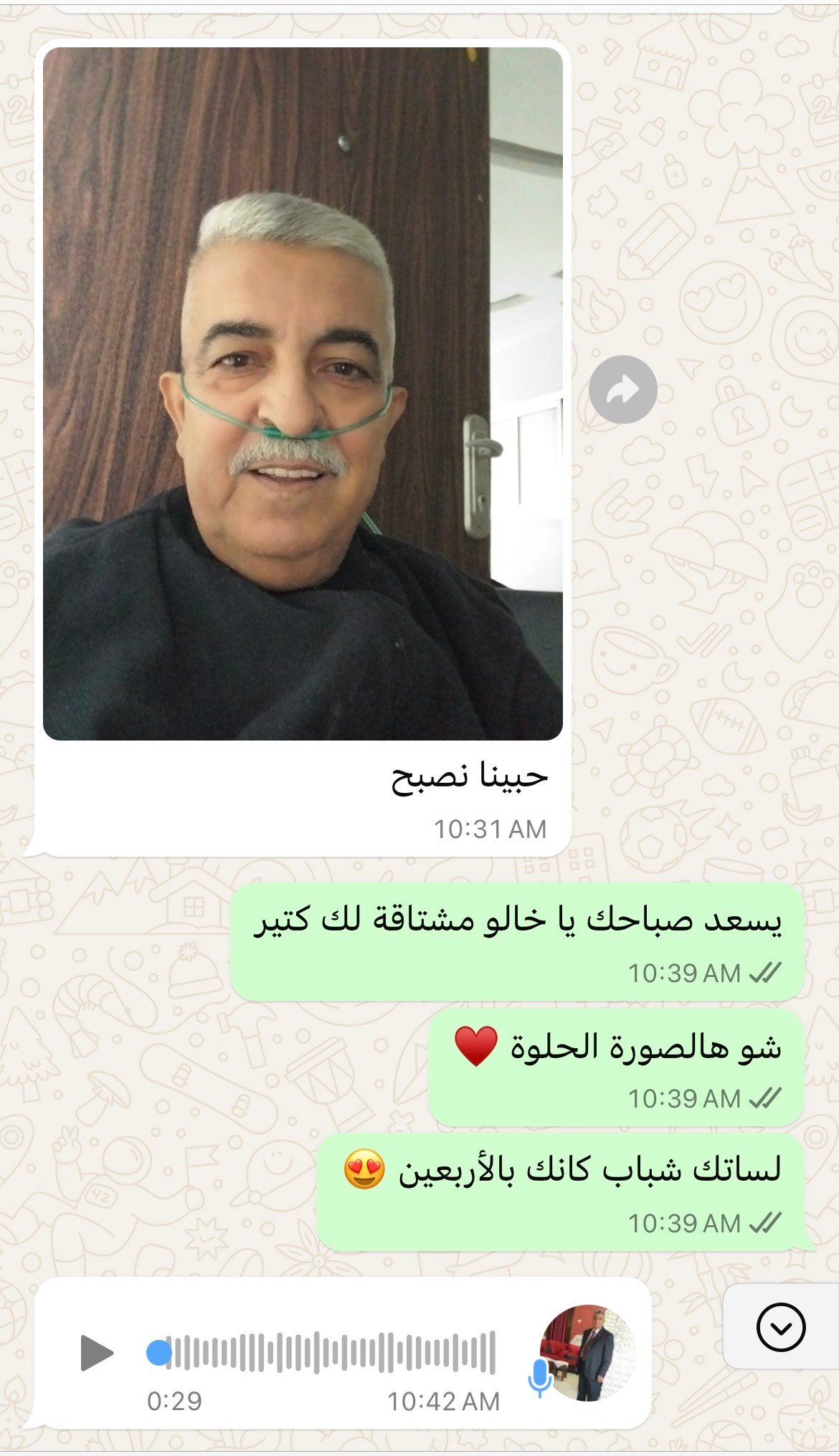

Just a week before he passed, almost as if he knew his time was coming, he sent me a photo of himself after getting a fresh haircut and shave. The oxygen tube was visible in his nose. He captioned the photo simply, “I just wanted to say a good morning.”

I replied: “What a beautiful photo, you look like your early forties! I miss you.” He sent me back a voice message: “Of course I am still young, but the war has made everyone feel old. Pray for us, and I miss you too my sweetheart.” That was the last conversation we had.

“He faced death not only from illness but also from starvation, destruction and the utter collapse of life as knew it.”

We all shared a special relationship with my uncle. He was the kind person whose heart was full of affection, a gentle soul loved by everyone. My memories of him are filled with warmth. When I was child, he always pampered us with sweet words, bringing a little light into a world that sometimes felt so cold. He would greet us with a kiss on the check and say the kindest things, making us feel seen and loved. One memory that stands out is when I was taking English lessons as a child. He would come with me to the language institute and every time we met after that he would speak to me in English, proud of our progress. When I earned my Ph.D., he was overjoyed, sending heartfelt messages of congratulations. He always made me feel like my accomplishments mattered to him.

My Uncle Mahmoud had a uniquely close relationship with my mother. He wasn’t just a sibling — he was also a friend, always by her side, supporting her. When my mom had to travel for a surgery in Egypt, I went with her, and he came with us too. We spent precious time together. He wasn’t just another uncle. He was someone irreplaceable.

Whenever I managed to visit Gaza, Uncle Mahmoud would always invite us for big meals, full of love and care. I had hoped to visit Gaza again, to see him and spend time together, but now that chance was gone. And with this war, who knows when it will end or when we will be able to reunite with our loved ones again. Goodbye, my dear Uncle Mahmoud. May your beautiful soul rest in peace. You will always hold a special place in my heart.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.