New Orleans – Louisiana voters approved an amendment to the state constitution on Tuesday requiring that jury verdicts for felony convictions be unanimous, putting an end to one of the last vestiges of Jim Crow on the state books. For decades, Louisiana has been one of the only states where a guilty verdict from only 10 of 12 jurors can secure most felony convictions — including for life sentences without parole. The practice dates back to the late 1890s, when post-Reconstruction Democrats worked to maintain white supremacy by passing laws that disenfranchised Black voters and filled prison plantations with people of color.

This legacy helps explain why Louisiana is a hotspot for wrongful convictions and has long held the title of the most incarcerated place on Earth. For years, Louisiana had a higher incarceration rate than any other state in the United States, which is the most incarcerated country in the world. However, recent reforms helped the state drop down to second place this year (Oklahoma now tops the list). At the statehouse in Baton Rouge and in the streets, campaigns to reduce incarceration in Louisiana and politically enfranchise former prisoners have been driven by formerly incarcerated activists. They trace their roots back to a political organization formed in the mid-1980s inside the walls of the infamous Louisiana State Penitentiary (known as “Angola,” after the plantation that previously occupied its grounds). Thanks to their efforts, Louisiana passed a law last year restoring voting rights for people with felony convictions who have been out of prison for five years, setting the stage for a similar measure in Florida that was approved by voters yesterday.

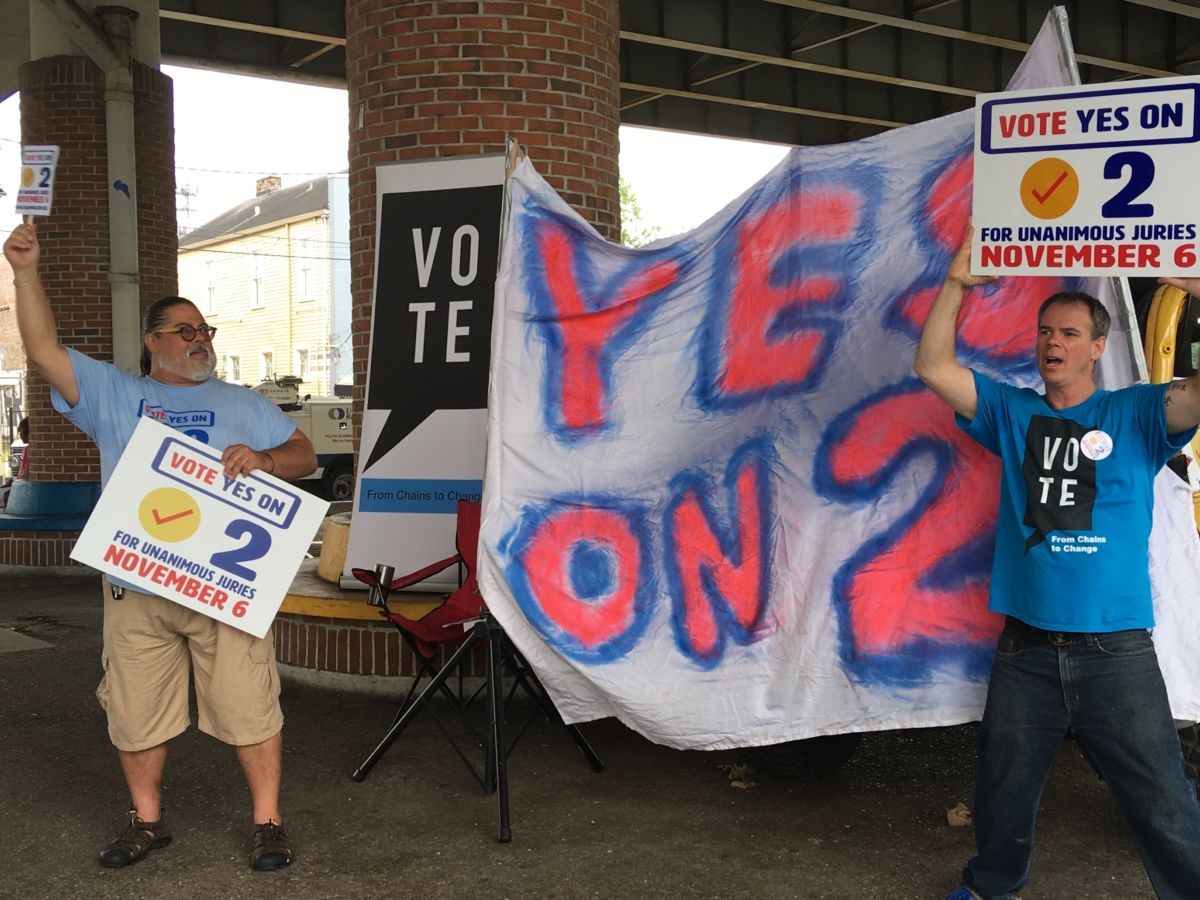

With the right to vote restored for thousands of people, formerly incarcerated Louisianans are participating in state politics in ways that would not have been possible years ago — including the campaign for unanimous juries. One example is Voices of the Experienced or VOTE, a grassroots organization founded and run by formerly incarcerated activists. To learn more, Truthout caught up with VOTE Deputy Director Bruce Reilly and Senior Policy Counsel Will Harrell in New Orleans on Election Day.

I understand that the movement toward getting this on the ballot started in the state legislature?

Bruce Reilly: It started before that with litigation; this issue goes back decades. There’s people who have been serving life sentences [due to non-unanimous juries], there’s been lawsuits filed for years and years, including by people who’ve been locked up in Angola and became jailhouse lawyers. People like Norris Henderson, our executive director at VOTE, who is now the statewide director of the Unanimous Jury Coalition. We had to name somebody, and Norris was perfect. He was convicted with a 10-2 verdict, along with many other people who are members of VOTE, people who, ultimately, sometimes, got their conviction overturned.

This has been a movement led by formally incarcerated people. What did that look like?

Reilly: Once it got to this level, and we knew that we had to do a real grassroots voter engagement plan, we knew we had to connect with people statewide, and fortunately for everybody in the coalition, there has been a lot of amazing people involved with all sorts of talents. But within our coalition are directly impacted people, most of whom are members of VOTE, Voices of the Experienced, which was created originally inside Angola penitentiary and goes back to 1986. A critical mass of those guys got out in the early 2000s, including Norris…. We’ve just been kind of doing the work and growing and growing and building our base, and now we have chapters in Baton Rouge, Shreveport and Lafayette. So, when [the unanimous jury issue] came about, it perfectly coincided with the work that we’ve been doing, including forming up with a statewide coalition.

Will Harrell: We did not anticipate a victory this year, but there were a lot of things set in motion several years ago, as Bruce has pointed out…. Three years ago, we passed a pretty Earth-shaking package of reforms to reduce prison populations in the world’s leading incarcerated state, but also, last year, along with the passage of this bill putting this measure on the ballot to amend the constitution to require unanimous juries, we passed legislation restoring the right of people with felony convictions to vote again. And so, as Bruce has pointed out, we have been building this movement of people directly impacted…. This campaign has given us the opportunity, and building up to it, we’ve identified thousands of people around the state who are now engaged in this legislative process and who are coming out. They are on the phones right now, they are texting people right now, they are delivering signs all over and they are putting up signs, they are waving signs like me and Bruce are doing out here today, engaged and excited. We don’t expect to just win today, we plan to win “bigly,” and in doing so, we’re sending a message to the political establishment that we are experiencing a paradigm shift in the state of Louisiana. [Voters approved the measure by a 64-36 margin.] You’re talking about a new 40,000 people in the state who can vote in March, who otherwise could not show up and vote on the next legislative session, and thousands more that come behind them. It’s time for the legislature and elected officials to sit up and look around and take account and realize that these are voices that matter, too.

You said you were kind of surprised it got on the ballot. This has been a thing in Louisiana for over a century. Why did it take so long for this to come up?

Reilly: It’s a critical mass, you know, all of these things have really come together. I mean, on any one particular victory lately, if anyone were to just kind of say, “Oh, that’s because of us or that’s because of me,” they are really missing the bigger culture shift, they are missing the wave that’s really happening. You know, when you’ve got a former [District Attorney] Republican senator saying on the floor that he’s voting for voting rights, not for the two Saints [football] players who wrote a letter, but for Chico, right? Our guy, Chico, who served 22 years in prison, he was one of the founders of VOTE and is basically a serious lobbyist now up at the statehouse. He’s a 72-year-old grandfather who is like, “I don’t have the right to vote.” [The lawmaker] said, “I’m doing this for Chico.” And that, to me, that was like, it summarized everything, you know…. I’ve been a part of this myself because I did 12 years in prison, and there’s some people who kind of want to hide us, you know…. We can try to end long sentences, end life sentences, end non-unanimous juries, end the death penalty, end juvenile [sentencing] without parole, somehow by talking about people convicted of misdemeanors or something. No, we actually have to show that humanity of people who’ve done 10, 20, 50 years in prison. People like Albert Woodfox, who did 43 years in solitary [confinement]. How are you going to talk about the inhumanity of solitary if you’re not going to show the humanity of someone who did 43 years in solitary?

What is next for decarcerating Louisiana after we get this passed?

Reilly: Well, there’s two biggest things that we are going to be working [on] — actually three. One is the actual implementation of Act 636, the voting rights victory, which is why we are paying close attention to the secretary of state race. Most people wouldn’t think that much about it, they might think it’s about paper ballots or something, or contracts, or polling machines. It’s really about whether or not they are going to support our voting right, or whether they are going to silently soft pedal and be against it. Because we know that most voting suppression happens by the government [officials] themselves…. Act 636 is a law that allows people who have not been incarcerated on the present sentence within the past five years to vote. So, for people on parole, if you have been out for five years, and you are still on parole, you can vote. If you are on probation and you’ve not been incarcerated because [you] went straight to probation — they all can vote. So, that’s about 43,000 people.

Harrell: We got to get them registered to vote and get them out to vote, but there are administrative procedures that have to be put in place for that to happen. And we’ve already heard reports from around the state that there are already some local registrars who ain’t feeling it, they ain’t ready for that change, but that’s the law and they are going to have to enforce it.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.