Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

Also see: Winnemem Wintu Fight for Cultural Survival in Northern California

Ann Marie Sayers walks by Cottonwood and Sycamore trees, stopping to examine poison oak. She gently cradles the leaves. “They don’t bother me. I have a relationship with them,” she says. And this relationship, Sayers knows, spans millennia. She is right at home in Indian Canyon, the only federally recognized Indian country for over 300 miles from Sonoma to the coast of Santa Barbara. “I was born and raised in the Indian Canyon. My umbilical chord was buried here,” she says.

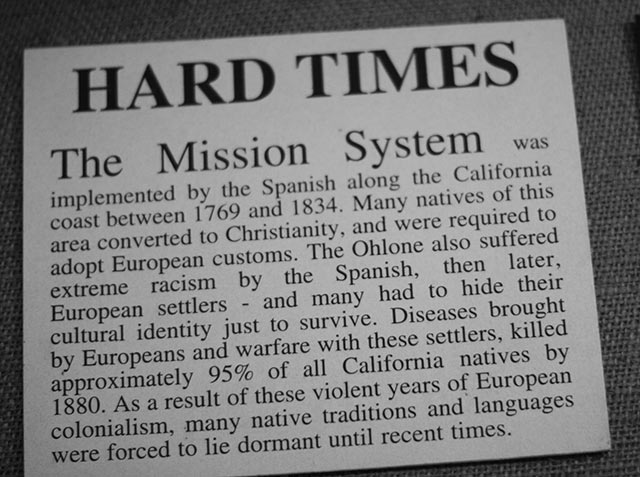

As a Costanoan Ohlone, Sayers is a rare example of a Native woman who continues to live in her ancestral land. California Indians suffered a brutal history of colonization, diseases and heinous violence and servitude during the Gold Rush and California Missions era. “This is the most exciting time to be alive as a California Indian since contact,” she says. “In 1854 alone, the government spent 1.4 million – $5 a head, 50 cents a scalp for professional Indian killers.” As the population of Natives precipitously shrunk during the Gold Rush, the Canyon served as a safe haven for those who were able to find it after passing through a swamp.

The canyon is a mile long and has lush streams and a cascading waterfall when the rains are plentiful. Sayers used the Allotment Act of 1887 to reclaim land that had been in her family for centuries in the Indian Canyon. “The canyon is alive through the power of ceremonies,” Sayers says. And she has taken to heart the painful history of religious persecution Native Americans endured, when they were prohibited from practicing their traditional spirituality until 1978. “My mother believed that when ceremonies stop, so does the Earth. And I do too. We opened up my great grandfather’s trust allotment for all Indigenous Peoples who need traditional lands for ceremonies.”

The canyon has a large arbor, where storytelling gatherings, cultural dances and ancient chants bring together Indigenous Peoples from around the world. The canyon receives thousands of visitors every year – from the Maoris of New Zealand to the Gwich’in of Alaska. “I can feel my ancestors dancing when there is ceremony,” Sayers says. The canyon is also home to the Costanoan Indian Research, Inc., which has ancient tools and artifacts that were used by Ohlones and ancestors of Sayers.

“It seems the society today is absent of the sacred. Many places that should have remained have been destroyed,” she says. Sayers has devoted her time to honor the legacy of her Ohlone ancestors and their sacred connection to land. Last year, she was involved in organizing efforts, where voters in San Benito County passed a measure to ban fracking.

Sayers remains committed to educating and empowering youth to reconnect their sacred relationship to Earth. “Today, people are shortsighted. When you make a decision, think how this will affect the next seven generations. And we need our youth to start thinking this way.” Last year, Sayers was also instrumental in organizing “Ohlone Elders and Youth Speak: Restoring a California Legacy,” an exhibit that illuminated the history of Ohlones and their efforts for cultural revitalization.

As we walk around the canyon, Sayers shares intimate stories of her family, and the canyon landscape and medicinal plants and trees dotting the property. “The Earth is alive. You can feel the energy. And it’s a reason for living.”

Indian Canyon is the only federally recognized Indian territory for over 300 miles from the coast of Sonoma to Santa Barbara. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Indian Canyon is the only federally recognized Indian territory for over 300 miles from the coast of Sonoma to Santa Barbara. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Ann Marie Sayers was born and raised in Indian Canyon. “Since Native Americans did not have the right to practice their religion freely until 1978, and so I opened up my great grandfather’s trust allotment for all Indigenous Peoples who are in need of traditional land for ceremonies,” shared Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Ann Marie Sayers was born and raised in Indian Canyon. “Since Native Americans did not have the right to practice their religion freely until 1978, and so I opened up my great grandfather’s trust allotment for all Indigenous Peoples who are in need of traditional land for ceremonies,” shared Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

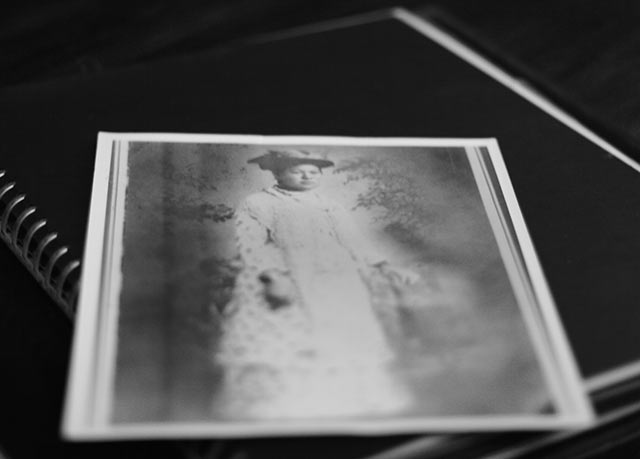

“My mother was a proud Indian woman. And she believed that when the ceremonies stop, so will the Earth,” shared Sayers about her mother, Elena Sanchez Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

“My mother was a proud Indian woman. And she believed that when the ceremonies stop, so will the Earth,” shared Sayers about her mother, Elena Sanchez Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Indian Canyon served as a safe haven for Ohlone people, who faced racism and brutal violence during the Gold Rush. A large swamp hid the mouth of the canyon, and those that were able to find the path to the canyon were safe. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Indian Canyon served as a safe haven for Ohlone people, who faced racism and brutal violence during the Gold Rush. A large swamp hid the mouth of the canyon, and those that were able to find the path to the canyon were safe. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

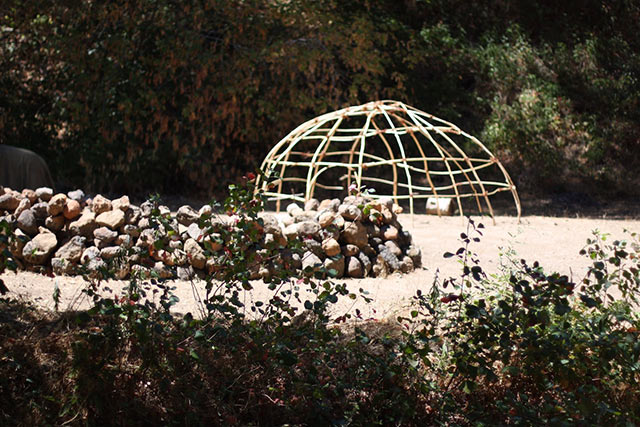

The canyon has a large arbor, eight sweat lodges and sites for vision quests. The canyon receives thousands of visitors every year, who gather here for storytelling, workshops, ceremonies and vision quests. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

The canyon has a large arbor, eight sweat lodges and sites for vision quests. The canyon receives thousands of visitors every year, who gather here for storytelling, workshops, ceremonies and vision quests. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

“Nature deficit disorder is very real in this society. We are absent of the sacred, outside of money,” remarked Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

“Nature deficit disorder is very real in this society. We are absent of the sacred, outside of money,” remarked Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

“They don’t bother me. I have a relationship with them,” said Sayers as she delicately touched the leaves of poison oak. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

“They don’t bother me. I have a relationship with them,” said Sayers as she delicately touched the leaves of poison oak. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Sayers founded Costanoan Indian Research, Inc., to educate the public about the history of Ohlone people and raise awareness on the violent legacy of the California Mission system and the Gold Rush, as well as ongoing efforts for cultural revitalization. “We need truth in history,” said Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Sayers founded Costanoan Indian Research, Inc., to educate the public about the history of Ohlone people and raise awareness on the violent legacy of the California Mission system and the Gold Rush, as well as ongoing efforts for cultural revitalization. “We need truth in history,” said Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

The canyon has a small ethnographic museum that has ancient mortar and pestles, baskets and other artifacts that were used by Ohlone people. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

The canyon has a small ethnographic museum that has ancient mortar and pestles, baskets and other artifacts that were used by Ohlone people. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Sayers has adorned her “Mother’s Spirit Rock” with abalone shells. “My mother believed that when a burial is disturbed, the spirit of that individual is wandering until that individual is re-interred ceremonially,” said Sayers, referring to the removal of Native American burials across the Bay Area to make way for shopping malls and housing development projects. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Sayers has adorned her “Mother’s Spirit Rock” with abalone shells. “My mother believed that when a burial is disturbed, the spirit of that individual is wandering until that individual is re-interred ceremonially,” said Sayers, referring to the removal of Native American burials across the Bay Area to make way for shopping malls and housing development projects. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

“Each bead is a prayer,” shared Sayers, who also makes traditional jewelry in the canyon. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

“Each bead is a prayer,” shared Sayers, who also makes traditional jewelry in the canyon. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Last year, Sayers organized a gathering to honor nine Ohlone elders as part of an exhibit called Ohlone Elders and Youth Speak: Restoring a California Legacy. “We need truth in history. It’s so important. The foundation of this country was built on the lives and death of Indians,” said Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Last year, Sayers organized a gathering to honor nine Ohlone elders as part of an exhibit called Ohlone Elders and Youth Speak: Restoring a California Legacy. “We need truth in history. It’s so important. The foundation of this country was built on the lives and death of Indians,” said Sayers. (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Sayers also offers the canyon to educate and empower youth to protect sacred sites and reconnect to their Native culture and spiritual traditions. “The Earth is alive. You can feel the energy. And it’s a reason for living.” (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Sayers also offers the canyon to educate and empower youth to protect sacred sites and reconnect to their Native culture and spiritual traditions. “The Earth is alive. You can feel the energy. And it’s a reason for living.” (Photo: Rucha Chitnis)

Republished with permission from Indian Country Today Media Network, where it originally appeared on September 30.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 500 new monthly donors in the next 10 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.