Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

In Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s recently published Guantánamo Diary, we learn what it’s like to be imprisoned and tortured without charge. When Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld signed the “Special Interrogation Plan” in August 2003, the author’s brutal treatment began. The tortures and humiliation he experienced are good reasons for closing Guantánamo and holding accountable those who authorized or carried out the abuse.

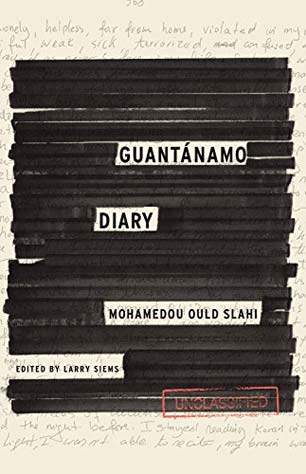

First published in January, Guantánamo Diary by Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Little Brown, 2015) is already a bestseller – as it should be. The story of Slahi’s first four years of what is now almost 14 years of incarceration shows the author as a man of courage, resilience and incredible humanity.

From his first arrest in January 2000 (broken only by an 18-month release), he endured a Mauritanian jail; renditions to Jordan and Afghanistan; and imprisonment at Guantánamo (from August 5, 2002 to the completion of his manuscript in the summer of 2005). And as noted below, he remains in that prison without charge to this day.

One hundred and eighty one pages of the 372-page volume cover Mohamedou’s first three years at Guantánamo. Yet the United States stage-managed his interrogations from the beginning. FBI and CIA officials believed he was behind the Millennium Plot to bomb the Los Angeles Airport and that he was a recruiter for al-Qaeda. They took an active part in both the Mauritanian and Jordanian interrogations.

Born in Mauritania in 1970, Slahi fit the terrorist profile: He was young, Muslim, multilingual and well traveled. He won a college scholarship to a German university, took a degree in electrical engineering and worked for a time in Germany. He served al-Qaeda in Afghanistan for two years in its jihad against the Russians. While in Germany, he kept in touch with friends who retained their al-Qaeda ties. A distant cousin and brother-in-law was Abu Hafs, a former adviser to Osama bin Laden. No surprise Slahi was a suspect.

Yet Slahi convinced his captors in Nouakchott and Amman that he was innocent of any crime. Only the Americans persisted in their belief that he was a high-level terrorist.

From the outset of his arrival in Gitmo, his hosts subjected him to 24-hour shift interrogations, a frigid isolation cell and sexual molestation. Slahi relates Kafkaesque exchanges he had with his guards and interrogators. “We’re stronger than you, we have more people, we have more resources, and we’re going to defeat you.” When Slahi became faint from a hunger strike, a guard told him “You’re not gonna die, we’re gonna feed you up your ass.” Another guard confessed: “I know I can go to hell for what I have done to you.”

For Slahi, the worst was to come. On August 13, 2003, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld personally signed off on a “Special Interrogation Plan” for Slahi. From then until December 2003, when he decided to confess to everything his interrogators put to him, Mohamedou suffered relentless torture: beatings, forced water diet, sleep deprivation, constant darkness, verbal abuse, blaring music, stress positions, threats to family and faked rendition by boat.

What is most striking to me about the book is Slahi’s empathy for others in the midst of his own suffering, not only for fellow prisoners in distress, but also for some of the guards who had tortured him. “I couldn’t help crying one day when I saw a German-descendent (redaction) guard crying because (redaction) got just a little bit hurt.”

Slahi learned English (his fourth language) while imprisoned. Fortunately, his unseen editor Larry Siems, preserved Mohamedou’s voice, with its colloquialisms and imitations of his captors’ language. Unfortunately, the 2,500 government redactions leave us guessing at many points beyond the blocked out names of the torturers.

As I read the book, some questions repeatedly came to mind:

• Why have those responsible for the Guantánamo torture not been held accountable, as required by international law?

• Why is Slahi, who has never been charged with a crime, still in Guantánamo? Yes, the Obama administration appealed a federal judge’s 2010 court order for his release, but why such delay for a rehearing? Could the US authorities be afraid that Slahi will publish an un-redacted version of his book in Europe?

Attorney Nancy Hollander and her associates deserve much praise for their seven-year legal campaign to liberate the manuscript. The book is a publishing landmark. Despite its numerous redactions and Slahi’s mostly understated descriptions of the tortures he endured, it reminds Americans that Guantánamo stills holds prisoners today who have committed no crime. Of the 122 men currently imprisoned at Guantánamo, 54 have been cleared for release.

The shame of Guantánamo will not end until those responsible for it and the torture within its walls are held accountable and the prison is closed forever.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.