In a tumultuous period of unrelenting setbacks to the goals of progressivism, take heart that the grassroots labor movement is acelerating a struggle against the oppressive pay and working conditions that result from neoliberalism. In this interview, Annelise Orleck, author of “We Are All Fast-Food Workers Now,” discusses worker uprisings around the world.

Mark Karlin: How is neoliberalism something that ties the uprising against poverty together around the globe?

Annelise Orleck: The ravages of neoliberalism have not been subtle. And they have been truly global. Essential services have been privatized. Since the dawn of the 21st century, free public schools and health care, safe, drinkable water [and] publicly controlled power grids have disappeared around the world — especially in poorer nations. And those who have fought for restoration have often been met with violence. We in the US have also seen public schools starved of funds and replaced by corporate-run charters, community clinics replaced by corporate for-profit medical facilities and natural water sources privatized for the commercial use of corporations. It is no longer so simple as to say that the worst labor abuses — the worst predations of neoliberalism — take place abroad while American workers have it better. We may have it better, but US workplaces are more dangerous than they have been in more than 70 years. And a majority of American workers do not make enough to comfortably pay their bills.

US workplaces are more dangerous than they have been in more than 70 years.

There are at least two dozen transnational corporations [that] have come to possess more financial and political power than most nation states. Those companies employ a great many people worldwide who have, in the past few years, come to see themselves as members of a global labor force. That has given them a sense of solidarity and leverage against some of the world’s largest corporations. But it has also made them learn about state and national labor rights that they fight to enforce…. Global dissemination of genetically modified seeds and produce and the imposition of intellectual property laws criminalizing farmers’ traditional seed exchanges have devastated small farmers worldwide. Transnational corporate land investments have caused massive dispossession of smallholders (by the hundreds of millions) and created a worldwide labor refugee stream. Many of these refugees have become farm workers in affluent countries.

Whether it’s fast-food workers in Tampa, garment workers in Cambodia, berry pickers in Baja California or small rice farmers in the Philippine Cordillera, people I interviewed for this book displayed sophisticated understandings about the flood of transnational capital that has washed over our planet in the last 40 years; World Trade Organization regulations that eviscerate national labor, environmental and land rights; and the willingness of local elites and politicians to employ violence in support of neoliberalism. And they understand that these are problems that poor people face worldwide.

Filipino labor organizer Josua Mata argues that global capitalism is the new colonialism. He recalls a moment in the early 1990s when that dawned on Philippine activists. “We were just starting to grasp what was happening,” he says, “that global organizing was essential.” In that moment, he says, it became clear that, to stay vital and relevant, the labor movement had to begin to think and organize as capitalists were already doing — globally. And they have.

Annelise Orleck. (Photo: Joel Benjamin)

Annelise Orleck. (Photo: Joel Benjamin)

Retail, fast-food, farm and manufacturing workers have revived, enlivened and rebranded global labor federations with roots in post-World War I internationalism: ITUC (the International Trade Union Confederation); the IUF (International Union of Farm, Food, Hotel and Tobacco Workers); and IndustriAll [Global Union]. Working with the AFL-CIO and American unions like UNITE-HERE (the hotel and restaurant workers’ union) and SEIU (the Service Employees International Union), hotel workers, fast-food workers and garment workers have staged global days of action drawing workers out on strike in hundreds of cities, in scores of countries on six continents. Farmers and farm-workers have formed global federations such as Via Campesina, the Peasant’s Road, which represents farmers in 72 countries. They have built alliances across national lines, staged global actions and they are pressing the United Nations to pass an international Declaration of the Rights of Peasants and others who work the land. In addition, they have engaged in civil disobedience actions, blocking dam construction, storing and exchanging heirloom seeds, forming vast human chains to block cultivation of fields with genetically modified seeds and holding fishing boat rallies to block factory fishing in their traditional fishing grounds. At times, they have paid with their lives.

Neoliberalism and patriarchy were intertwined and disproportionately impoverished and preyed on women and children.

These movements are growing. They show no signs of abating, despite the risk. As Bangladeshi garment union leader Kalpona Akter told me: “You can’t live your life if you are always afraid of dying.”

Explain the quotation: “You can’t dismantle capitalism without dismantling patriarchy.”

This was said to me by a 27-year-old Filipina labor feminist named Joanna Berniece Coronacion, whose nom de guerre is “Sister Nice.” Her framing of the struggle faced by young feminist workers like herself drew on what she had learned as a leader in the Philippine Alliance of Progressive Labor and the RESPECT! Fast Food Workers’ Alliance, but was also shaped by her involvement in the Manila chapter of a global women’s alliance called World March of Women (WMW).

Founded in Quebec in the mid-1990s, WMW argued that neoliberalism and patriarchy were intertwined and disproportionately impoverished and preyed on women and children. World March has worked to link women peace activists, trade unionists and feminists across the globe. Every five years since 1995, World March has staged months-long marches involving women in every part of the world. These women activists gathered millions of signatures, which a march of 10,000 women delivered to the UN in 2000, demanding an end to violence against women and remediation of the damages to women and children caused by neoliberalism and war. In 2010, they gathered in Congo and testified to war crimes on both sides of the conflict. They successfully pushed for a US ban on importation of products made with conflict minerals. In 2015, they visited Syrian refugees in Turkey, bringing books and vegetable seeds. Every year on International Women’s Day, World March members, including thousands in the Philippines, hold rallies and protests … to highlight the relationship between neoliberalism and patriarchy. Across the Philippines, women linked reproductive rights and land grabs, chanting “No to corporate occupation of our lands, no to occupation of our bodies.”

Most of the world’s service and retail workers, small farmers and contract workers are women. Desire for gender justice — wage parity, greater representation in government, business and unions, an end to pregnancy discrimination and gender-based violence in the workplace — has fueled their growing militancy. From the tomato fields of Florida to the export zones of the Dominican Republic, Bangladesh and Malaysia, women workers are organizing. Many share Sister Nice’s view of what work needs to be done.

Can you expand on your statement: “What is true is that almost no garment workers earn a living wage”?

The global garment industry tripled in size between 2005 and 2015. In 2000, there were 20 million people making clothes worldwide; by 2015 there were between 60 and 75 million garment workers, almost all of them women. In those same years, more than 4,000 “export processing zones” were created in countries around the world where national labor laws and environmental regulations do not apply. Global garment producers have flocked to those zones, which now employ more than 66 million people. The vast expansion of the “rag trade,” along with the implementation of “fast fashion” production techniques, have driven down wages for garment workers around the world. By 2013, garment workers everywhere were making less than they had 10 years earlier. In Mexico and the Dominican Republic — both major apparel exporters — garment workers’ wages declined by one-third in that time. Garment workers in China and Indonesia were earning just a third of what they needed to pay their bills. In Vietnam, where the sneaker maker Nike employs millions, they earn just one-quarter. In Bangladesh — the world’s second-largest exporter of clothing — workers were earning just 14 percent of what they needed to survive.

Those are the conditions that motivated them to rise up — and since that time, wages in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Malaysia and Ethiopia have risen. Nike’s Girl Effect foundation argued that garment work was giving girls in poor countries “control over their futures … many for the first time.” Kalpona Akter laughs at that idea, challenging consumers to try to live for a while as garment workers in Bangladesh do and see if they feel “liberated.”

How can a behemoth exploiter of labor such as Walmart be organized for better wages?

When Venanzi Luna and Denise Barlage — workers at the Pico Rivera, California, Walmart — led the first strike against the corporate giant on US soil in 2012, they were terrified. They were among associates from nine stores in the Los Angeles area who had decided to walk out. Walmart was known for striking back at employees who raised their voices for better pay and conditions. One Quebec Walmart that had unionized was shut down entirely. (So would the Pico Rivera store be, for a while anyway.)

So many working people in this country are really, actually hungry all the time and they have used hunger strikes to get that point across.

“Any time a worker stood up for herself,” recalled Evelin Cruz, “there was extreme retaliation.” Cruz was infuriated by the cruelty that managers displayed toward workers. She believed that Walmart engaged in what she called “predatory hiring,” bringing on workers who could not afford to speak out: single moms, disabled people [and the formerly incarcerated]. But then, says Luna, “we found out that we didn’t just have to take it.” The United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) taught her and other Walmart employees what their rights were under state and federal law, and how to file Unfair Labor Practices when those rights were violated. “I told my managers they had to put up a poster on the wall so workers can see their legal rights. They didn’t like that.”

During the 2012 walkout, LA-area Walmart workers were supported by a visiting delegation of union Walmart workers from Italy, Spain, Uruguay and South Africa, among other countries. They began to get a sense of just how global their struggle could be and would have to be. They created a Walmart Global Union Alliance…. They helped pay for Bangladeshi garment worker activist Kalpona Akter to travel to the Walmart shareholder’s meeting to describe to the gathered thousands the … conditions under which clothing sold in Walmart is produced. And they cheered when she challenged the Walton family to take 1 percent of their annual dividends to make needed safety repairs to their Bangladeshi factories.

Since 2012, Walmart workers across the US have walked out every year on Black Friday, the busiest shopping day. They have fasted outside the Park Avenue apartment of Walmart heiress Alice Walton and the Carmel, California, mansion of then-Walmart chair Greg Penner. “The thing that so many Americans don’t seem to get,” says Barlage, “is that Walmart workers and McDonald’s workers and so many other working people in this country are really, actually hungry all the time.” They have used hunger strikes to get that point across.

They have also filed numerous Unfair Labor Practice complaints, most of which have been upheld by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). How that will change in the age of Trump remains to be seen. But again and again, NLRB members and judges have ordered Walmart to rehire fired workers, to stop retaliating against those who try to organize, to observe rules mandating breaks, overtime and workmen’s compensation.

In recent years, much labor migration has been involuntary.

Pregnant workers organized by LA mother of seven Girshriela Green into a national group called Respect the Bump have sued and won agreements from Walmart to provide accommodations for pregnant workers. They were part of the landmark 2015 Supreme Court case — Young v. UPS [United Parcel Service] — that made it mandatory nationally for corporate employers to accommodate pregnant workers.

The workers know that there is a long way to go. Walmart has made gestures toward raising the wages of workers, though they have usually shut down stores and cut back on benefits when they do. Still, says Luna, “people never expected Walmart workers to take a stand against the world’s biggest company. But you know what? If we can change Walmart, we can change everything. People don’t realize how much power they have as workers. But if you put your little bit of rights on the line and go from that, you can change anything in the world.”

Where does agrarian reform fit into the global uprising?

The 2010s have seen a global refugee crisis on a scale not seen since World War II. Between wars and famines, economic distress, eviction and dispossession, upwards of half a billion people are on the move. This is about 1 in 14 people on Earth. Mostly when people think about labor migration, we picture rural people moving to cities or other places where workers are needed. But in recent years, much labor migration has been involuntary.

Around the time of the 2008 global recession, there was a spike in food prices globally that fueled protests from Haiti to Indonesia, from Cameroon to Uzbekistan. The world’s nations met in rising panic to seek “food security.” In the years after 2008, wealthy nations and corporations redoubled their commitment to the so-called Green Revolution, begun in the 1960s to “modernize” agriculture in poorer nations by promoting “hybrid” and GMO seeds, (protected by intellectual property laws, of course). Farmers’ seed exchanges were criminalized in many countries. Also, GMO seeds killed off thousands of varieties of indigenous corn and rice in Haiti, Mexico and the Philippines, to name just a few places. The Philippines had produced cold-resistant, high-protein rice 2,000 feet above sea level for millennia. Now it became the world’s largest rice importer. Africa, which had been in the 1960s a food exporter, was reduced to importing 25 percent of what its people needed to eat. Some farmers blamed bio-engineered seeds — and the costly pesticides and fertilizers they require — for deepening debt. Indian activist Vandana Shiva even called them “suicide seeds,” because she believes they contribute to the frightening spate of farmer suicides in India, which … is now spreading to other parts of the world. After the 2010 Haitian earthquake, Bill Clinton apologized for pushing industrial American rice on Haiti and destroying the indigenous rice market.

The second factor in fueling an agrarian uprising was a post-2008 land grab. Nervous investors in Europe, Asia and the Americas began looking for safe places to put their money. A corporate scramble for land ensued across Asia, Africa and the Americas, the likes of which had not been seen since the colonial powers in the 19th century. Governments in Africa and Asia eased the way for foreign agribusiness investment. Palm oil, rubber and sugar plantations swallowed up huge swaths of rainforest. Millions of farmers lost land and income. To earn desperately needed cash, farmers began to grow on contract for foreign corporations. Debt deepened. Foreclosures skyrocketed. Small farmers around the world experienced what activists call “agrarian reform in reverse.”

In South Africa, 2 million people were evicted. In Mexico, after NAFTA, millions lost farm lands and farm jobs. Across Asia, small farmers lost tens of millions of acres of land. Hundreds of millions were forced to migrate in search of work. Millions of these labor refugees became the undocumented farm workers who grow and harvest food in every affluent nation. Even as huge corporate agribusiness projects were sweeping the world, scientists for the UN Food and Agriculture [Organization] found in 2014 that small farmers, most of them women, still provided 70 percent of the world’s people with their food. Small, eco-agriculture, they agreed, was the best route to real food security.

In red states as well as blue, voters are casting ballots for wage increases.

Moving against dispossession and for renewed support of small farmers, in 2017, peasants and farm-workers staged “uprisings of the landless” around the world. Their slogan was “No Land. No Life.” In March, farmers and farm workers protested from Brazil to India, from the Philippines to Pakistan, from Oaxaca to Orange County. In April, they staged protests around the world to mark the “International Day of Peasant Struggle.”

… In May 2017, Via Campesina, IUF, global unions, farmers’ and women’s groups, descended on Geneva to try to hammer out a UN “Declaration of the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Agriculture.” The delegates concluded: “The relationship with Mother Earth, her territories and waters is the spiritual, cultural and physical basis for our existence…. We gladly assume our role as her guardians.”

What is the importance of the fast-food workers’ revolt for a $15 wage?

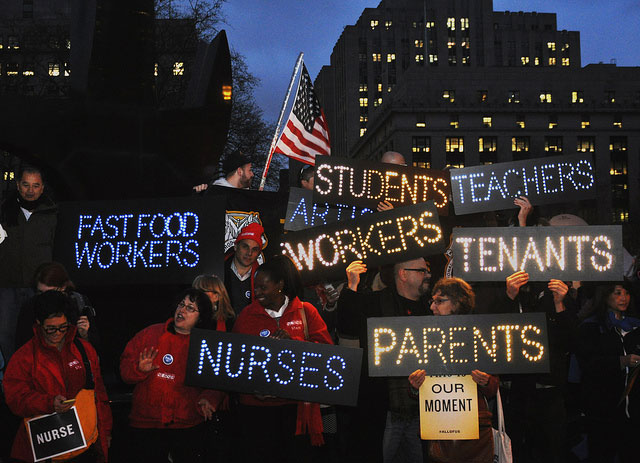

On November 29, 2016, three weeks after the election of Donald Trump, low-wage workers protested in 340 US cities for a living wage, paid sick leave and union rights. Hundreds were arrested in civil disobedience actions across the country. Undocumented immigrants, who make up a sizable percentage of this country’s lowest-paid workers, participated despite the risk. In Manhattan, fast-food workers, Uber drivers and bike messengers sat down in the middle of Broadway singing “We Shall Not Be Moved.” In Las Vegas, fast-food workers, home health care workers and pre-school teachers protested in front of several McDonald’s on the famed Strip, carrying menus of McShame and warning that “McJobs Hurt Us All.” In 20 of the country’s biggest airports, baggage handlers and retail workers, wheelchair attendants and security guards staged slowdowns for union rights. They called it “Day of Disruption.” Most of the disrupters were African American and Latinx, but they were also white, Native and Asian.

Protesters, explaining why they were participating, offered a clear-eyed view of the 21st century economy from the bottom up. Nearly two-thirds of jobs created since the 2008 recession did not pay a living wage. And the US Bureau of Labor Statistics was predicting that 60 percent of jobs created through 2020 also would not pay workers enough to live on….

Activists in the low-wage workers’ movement are rightly proud of what they have achieved between 2012 and today. The Fight for $15 movement, begun by a group of NYC fast-food workers in 2012, has spread to include a wide range of low-wage workers: retail, home health care, airport workers, fast food and even adjunct college professors. Between 2012 and 2016, 21 states plus Washington, DC, raised their minimum wage. In 2016, the country’s two largest labor markets — the states of New York and California — adopted gradual phase-in of the $15 wage. Nineteen states raised their minimum wage rates in 2017. Nineteen states raised their minimums in 2018. And by 2017, 40 localities had adopted minimum wages that were higher than those of their states.

In addition, the movement has changed public opinion dramatically. When fast-food workers began organizing in 2012, most Americans thought the idea of more than doubling the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour was delusional. By 2016, 6 in 10 Americans supported the $15 minimum. And that sentiment crossed party lines. In red states as well as blue, voters are casting ballots for wage increases.

Though $15 an hour is hardly a princely sum, it adds up. Between 2012 and 2016, workers earned themselves $61.5 billion in increases for 19 million workers. That is 12 times what Congress gave American workers when they last raised the federal minimum wage in 2007. They have also begun winning paid sick leave in states and cities across the US. Some cities have even enacted paid “safe days,” during which workers can recover from incidents of domestic or sexual violence.

Workers understand that this is just the beginning, says Laphonza Butler, co-chair of the Los Angeles living-wage coalition and president of California’s hospital and home care workers’ union, the nation’s largest union local…. But, she says, these raises matter, particularly after 40 years of wage stagnation. Plus, small economic victories pay large psychological dividends.

“When you’re in communities that have been economically strangled,” she says, “you see people who are broken, people who are so distracted by their everyday struggles they are hopeless. We felt the living-wage campaign could be a ray of hope, something that could unite people around winning something for themselves, for their families. No one else did it for them.”

That makes LA 19-year-old fast-food worker, Fight-for-$15 activist and college student Samuel Homer Williams feel really good. “For me it’s about being part of history,” he says. “Something bigger than myself. I kind of feel like a hero knowing that I’m helping people stay in their homes, pay their bills and be able to eat. That’s something that a lot of people haven’t been able to do lately. We’re trying to change that. And I think we will.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.