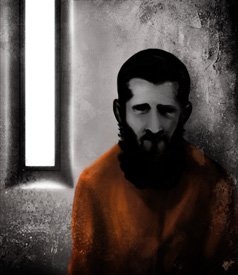

For Fayiz al-Kandari, one of the last two Kuwaitis in Guantánamo, American justice has always been an oxymoron. Although he has maintained – for nearly nine years – that he is an innocent man, and although the U.S. government has no evidence against him, he was put forward for a trial by Military Commission under President Bush, and, last Friday, lost his habeas corpus petition in the District Court in Washington D.C., consigning him, on an apparently legal basis, to indefinite detention in Guantánamo.

Nevertheless, throughout his long detention, al-Kandari has refused to let his disappointment with the U.S. justice system drag him down, and has found the strength to joke about it whenever he is visited by his lawyers. As his military defense attorney, Lt. Col. Barry Wingard, explained in an op-ed in the Washington Post in June 2009:

Each time I travel to Guantánamo Bay to visit Fayiz, his first question is, “Have you found justice for me today?” This leads to an awkward hesitation.

“Unfortunately, Fayiz,” I tell him, “I have no justice today.”

Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly’s unclassified opinion has not yet been published, so the details of her reasoning are as yet unknown, but enough of al-Kandari’s story has been reported to understand the weakness of the government’s case, and it beggars belief that a sound reason for denying his petition could have been conjured up at the last minute.

Al-Kandari, who is from a wealthy family in Kuwait, and has a history of providing humanitarian aid in countries where Muslims were suffering (in Bosnia in 1994, and in Afghanistan in 1997), has persistently stated that he arrived in Afghanistan at the end of August 2001 on a humanitarian aid mission that involved building two wells and repairing a mosque for a small rural community. He has also repeatedly stated that, sometime after the U.S.-led invasion in October 2001, he set off for Pakistan, after being shown a leaflet that had a picture of an Afghan holding a bag with a dollar sign on it, accompanied by some text, which, in essence, said, “Turn in Arabs and this will be you,” but was then seized by Northern Alliance soldiers who subsequently sold him to U.S. forces.

The U.S. authorities do not dispute the date of his arrival, but they claim that, in the three to four months before his capture in December 2001, he visited the al-Farouq training camp (the main training camp for Arabs in the years before 9/11) and “provided instruction to al-Qaeda members and trainees,” served as an adviser to Osama bin Laden, and “produced recruitment audio and video tapes which encouraged membership in al-Qaeda and participation in jihad.”

However, as I explained in a major profile of al-Kandari for Truthout in October 2009:

[T]he government has never attempted to explain how he “provided instruction to al-Qaeda members and trainees” at al-Farouq, when the camp closed less than a month after his arrival in Afghanistan, and, more importantly, how he was supposed to have undertaken all this training, provided all this instruction and advice, and produced videos and audiotapes during the small amount of time that he actually spent in Afghanistan.

At a military review board in Guantánamo in 2005, al-Kandari attempted to expose the implausibility of these allegations, when he asked:

At the end of this exciting story and after all these various accusations, when I spent most of my time alongside bin Laden as his advisor and his religious leader … All this happened in a period of three months, which is the period of time I stayed in Afghanistan? I ask, are these accusations against Fayiz or against Superman?

Despite this, the authorities have refused to accept al-Kandari’s account of his activities, even though a cursory glance at the allegations against him demonstrates that, of the 20 allegations against him, 16 are attributed to an unidentified “individual,” and only one – a claim that he “suggested that he and another individual travel to Afghanistan to participate in jihad and … provided them with aliases” – came from al-Kandari himself (and has been refuted by him).

Do you like this? Click here to get Truthout stories sent to your inbox every day – free.

The paucity of evidence is so extreme that, after his Combatant Status Review Tribunal in 2004 (a deliberately one-sided process designed to rubber-stamp the men’s prior designation as “enemy combatants”), the tribunals’ legal advisor made a point of dissenting from the tribunal’s conclusion that he was an “enemy combatant,” stating:

Indeed, the evidence considered persuasive by the Tribunal is made up almost entirely of hearsay evidence recorded by unidentified individuals with no first hand knowledge of the events they describe.

As researchers at the Seton Hall Law School noted, in a major analysis of the CSRT documentation, entitled, “No-Hearing Hearings” (p. 34), “Outside of the CSRT process, this type of evidence is more commonly referred to as ‘rumor.'”

Although these “rumors” were sufficient for the Pentagon to regard him as a prisoner of such significance that he was put forward for a trial by Military Commission in October 2008 (which has not been revived under President Obama), it is difficult to escape the conclusion that, inside the prison, he is regarded as a threat not because of what he is supposed to have done prior to his capture, but because of his attitude in detention.

The fact that the majority of the allegations against him were made by other prisoners is largely a testament to his own resistance, As one of Guantánamo’s least compliant prisoners, he has not fought back physically, but has refused to make false confessions implicating himself or others, as so many others have done under duress (and as the judges in the District Court have been exposing in other habeas petitions).

This is in spite of the fact that, in 2003 and 2004, when Donald Rumsfeld imported a version of the CIA’s torture program to Guantánamo, he was subjected to a vast array of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” which, as Lt. Col. Wingard described them, “have included but are not limited to sleep deprivation, physical and verbal assaults, attempts at sexual humiliation through the use of female interrogators, the ‘frequent flier program,’ the prolonged use of stress positions, the use of dogs, the use of loud music and strobe lights, and the use of extreme heat and cold.”

Even now, he is regarded as one of a handful of prisoners whose perceived influence over his fellow prisoners is such that he, and others who could not be “broken,” are separated from the general population of the prison.

As I stated at the start of this article, Judge Kollar-Kotelly’s unclassified opinion has not yet been published, so it is unclear where, in the barrage of “hearsay evidence recorded by unidentified individuals with no first hand knowledge of the events they describe,” she concluded that there was sufficient evidence to deny his petition.

Certainly, the habeas legislation is not without fault, although it has delivered victories for the prisoners in 38 out of 55 cases to date. A particularly startling example of these shortcomings was revealed last August when, in the case of a Yemeni, Adham Ali Awad, who was handed over to Afghan forces by al-Qaeda fighters in a hospital where he was a patient, Judge James Robertson denied his petition, even though he conceded that, “The case against Awad is gossamer thin,” and added, “The evidence is of a kind fit only for these unique proceedings and has very little weight.”

Tom Wilner, an attorney in Washington D.C., who represented al-Kandari and the other Kuwaiti prisoners in the early days of Guantánamo, and was counsel of record in the Supreme Court cases granting the prisoners habeas corpus rights (in Rasul v. Bush in June 2004, and Boumediene v. Bush in June 2008), explained to me on Friday how it was possible for prisoners to lose their habeas petitions on the basis of “gossamer thin” evidence.

“It is important to bear in mind that the standard for habeas is quite low; it only determines whether there is probable cause for detaining someone, not that the person has done anything wrong,” Wilner told me. He also added further criticism of the Bush administration’s detention policy, as maintained by President Obama.

Despite Friday’s result, he explained, al-Kandari “has not been convicted of any wrongdoing, yet he has been imprisoned for more than eight years. The low standard for habeas might be an appropriate standard for detaining someone initially, but it is hardly an appropriate standard for holding people for years without end.”

None of this helps Fayiz al-Kandari, whose lawyers must now either appeal or attempt to arrange a repatriation program between the U.S. and Kuwaiti governments. The first looks like a doomed enterprise, given the right-wing bent of the D.C. Circuit Court, which has recently been attempting to extend the government’s detention powers, rather than placing limits on them, and the second is hardly a better option.

In April, when discussions were proposed regarding the repatriation of al-Kandari and of the other Kuwaiti prisoner, Fawzi al-Odah, who lost his habeas petition last August, the Obama administration attempted to impose ludicrous security demands on the Kuwaiti government before talks could begin. These included demands that two men released last year after winning their habeas petitions – Khalid al-Mutairi and Fouad al-Rabiah (who, notoriously, was tortured into making false confessions that he was taught to repeat) – “have their passports taken away, be required to check in with local authorities regularly and be under surveillance by the Kuwaiti government for a period of time.”

So is Fayiz al-Kandari some sort of threat to the United States? Nothing I have ever seen or heard about him suggests that he is. When I interviewed Tom Wilner for the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (which I co-directed with Polly Nash), Tom spoke about a Kuwaiti prisoner who, from childhood, had allocated half his allowance to those more needy than himself, and described him as “a wonderful guy.” I had always suspected that the prisoner he was referring to was Fayiz al-Kandari, and on Friday, I asked him if this was the case.

Tom confirmed that it was indeed Fayiz he was referring to, and also told me, “He is extremely bright, with a wonderful smile and sense of humor and an almost poetic ability to express himself. He was absolutely dedicated to helping others and fighting any injustice inflicted upon them. At the same time, he was much stronger than I could ever be in withstanding personal abuse and injustice inflicted upon himself.”

Tom also told me that Fayiz “repeatedly expressed the view that Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda were seriously misguided, that their views were a perversion of Islam and that harming innocent civilians is a sin.”

Given Fayiz al-Kandari’s resilience, it is almost certain that he greeted Judge Kollar-Kotelly’s ruling with the strength of character identified by Tom Wilner, and with the playful dismissal of American justice with which he regularly greets his attorneys on visits to Guantánamo. His strength, however, should not blind us to the fact that, nearly nine years after his capture, there is nothing worth celebrating in the judge’s ruling – or in his continued detention.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $24,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.