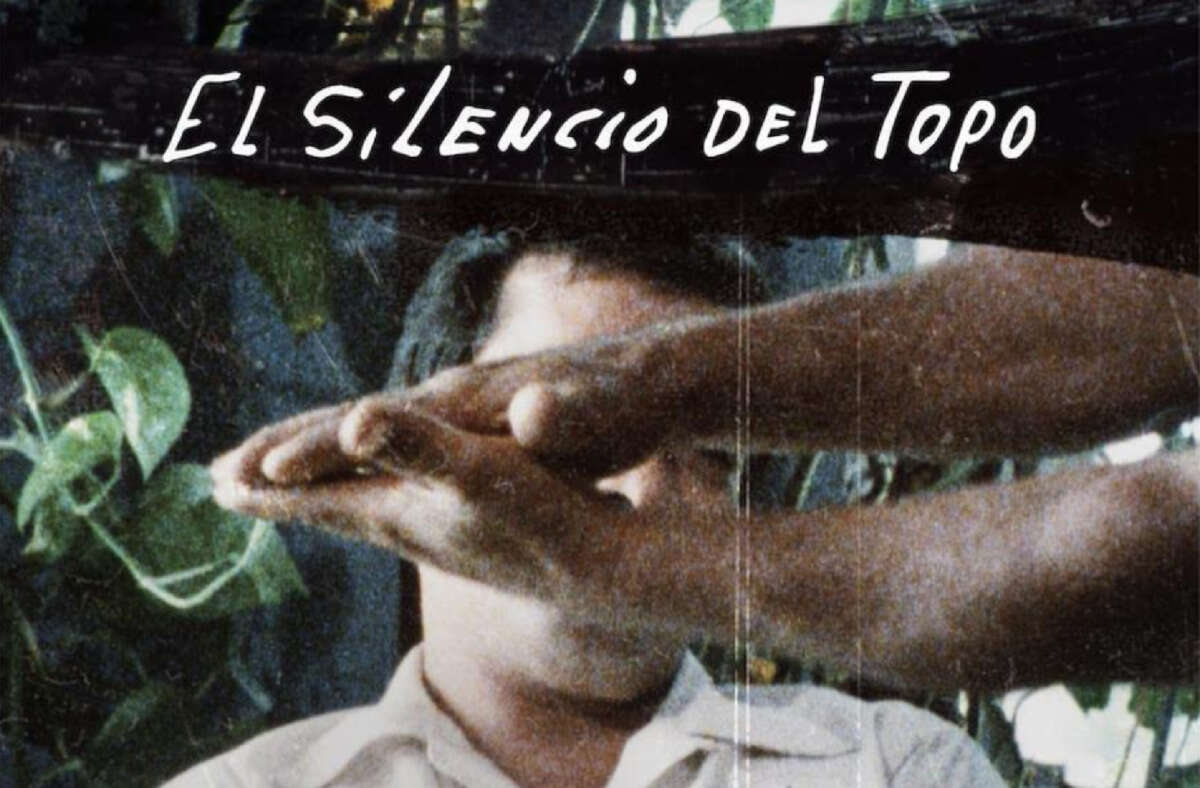

For more than six years, Guatemalan-French director and producer Anaïs Taracena documented, collected footage, conducted interviews and researched the repressive regime of 1970s Guatemala. El Silencio del Topo (“Silence of the Mole”) is Taracena’s debut feature film, a melancholy documentary that bridges the country’s erased past with the present.

El Silencio centers the story of Elías Barahona, a journalist who infiltrated the government as the press secretary for interior minister Donaldo Álvarez Ruiz. Barahona scheduled interviews, press conferences, and concealed information from the public for one of the men responsible for Guatemala’s internal war, which is estimated to have killed or disappeared more than 200,000 people and displaced 1.5 million Guatemalans. His colleagues considered him a traitor for many years not knowing that for Barahona, this was an undercover assignment. Barahona would eventually flee Guatemala with his two daughters in the middle of the night and expose the atrocities to the world.

Taracena interweaves never-before-seen images of the mass genocide (in large part because many were destroyed by the Guatemalan government of the time) with interviews of survivors and Barahona’s own daughter. Taracena narrates the film with sad poetic words because “to be able to tell it, you have to make cracks on the walls of silence in a country where [fear is still felt].”

El Silencio del Topo puts you face to face with the reality of genocide and doesn’t let you look away — a reminder of the power of journalism. The audience gets a raw and sometimes painful account of those who lived under the reign of terror and the remnants left behind.

Toward the end of the film, the audience is introduced to the son of Barahona’s former close friend and fellow journalist Marco Antonio Cacao Muñoz, also known as Maco Cacao. Cacao was brutally murdered in 1980 for upholding the truth about government violence in his news radio reports. His son shares a note he found in his father’s agenda that encapsulates the power struggle faced by Guatemalans.

“No hay temor que sepulte las ideas

Ni muerte que ponga fin a la

inteligencia

La represión es el arma de los

ignorantes

que buscan el poder de la riqueza

para seguir aplastando los oprimidos

Una muerte física solo provoca el

adiós terrenal

Que es dulce en comparación con el

castigo que sufrirán los causantes”

“There is no fear that buries ideas

Nor death that puts an end to

intelligence

Repression is the weapon of the

ignorant

who seek the power of wealth

to continue crushing the oppressed

A physical death only causes an

earthly goodbye

Which is sweet compared to the

punishment that the perpetrators will suffer”

– Maco Cacao

The documentary has been screened at a multitude of festivals, ranging from the International Film Festival of Human Rights in Switzerland to Palestine Cinema Days in historic Palestine, and has won more than 20 awards since its 2021 screening premier in Guatemala. The film is headed to the 39th edition of the Chicago Latino Film Festival this month with the next screening scheduled for April 19.

The following is an interview with Taracena that has been lightly edited for clarity.

Jocelyn Martinez-Rosales: Sometimes during the film, it’s hard to distinguish the present from the past. Was that a choice deliberately made in the cinematographic language of El Silencio del Topo?

Anaïs Taracena: The aesthetic and also narrative decisions were the fruit of precisely that investigation. I had some clear ideas: I wanted Guatemala City, the downtown area, to be very present because that is where Elías worked.

Sometimes the language is very timeless. You don’t know what era you are in and you still feel that weight of the past, a lot, and it is very subtle. It is as much in people’s bodies as it is in the walls.

I also knew that I wanted to work on the light and dark areas a bit. I wanted to work with archives, but the decisions were also worked on later in the investigation — for example, with Carla Molina, who is the director of photography. We talk a lot. In some places we had little time to film. Or we filmed landmarks and we really wanted places to talk, too. Sometimes we had a day or very little time to film the places, and in that sense, Carla, who is very good, contributed a very cinematographic eye.

Elías Barahona’s story is very impressive and I wonder about its popularity in Guatemala. Do people know his story?

My generation and the newer generations don’t know this story. I had no idea who Elías was, right? Elías was a university professor in Guatemala, so the students who were his, more or less, knew a little about his history without so many details. But really, since we began showing the film in Guatemala, the public was very shocked because they did not know that story. Even people of Elías’s generation, who did know his story, did not know it in such detail. It had always held an ambiguity of what had transpired.

How did you come across Elías given that you mention that he wasn’t very well-known?

I met him through his brother, David Barahona. The first time I made a short film called De Tripas Corazón, it is a very simple short film that I filmed and edited alone. I filmed Elías’s brother, David, who passed away, too. He lived in Paris and had arrived as a political refugee in 1983. I decided I wanted to work on the topic of exile and it has always been a topic that interests me due to my family’s own history.

David knew my family from when I was little and he always talked to me about Elías; he told me, “You have to meet my brother.” He gave me a short novel that Elías had written. When I arrived in Guatemala at the end of 2011, I contacted Elías and Elías already knew who I was through his brother, right? So I brought him a VHS tape that had been shared with me, a two-minute interview with Elías. Elías had never seen it. They had filmed him in the ‘80s, and I use that interview in the documentary. For me it was very striking, because that moment is where a friendship with Elías began.

At that moment, I had neither the intention nor any idea that it was going to be a documentary. In a way, life was guiding me towards that. I feel that the story came to me with great force and I don’t know how to explain it because after Elías dies, I film him in this trial because he asks me to film him, and Elías dies two weeks later. And it was after the death of Elías that I really decided to start making the documentary.

I feel that sometimes life led me to that. It’s like when a story comes to you, it falls on you and it is all very complicated. Elías was no longer here, there were no images. It was a very sensitive issue because you still can’t talk about counterintelligence in Guatemala, not yet. It’s not necessarily a topic that people want to talk about. But I felt a very deep need. I said no, I have to do it, I have to investigate and I knew that Elías wanted that story to be told and Elías had always thought of film as a way to do it.

I think that wherever he is, I feel that he is very, very happy.

You mention that you have a personal connection with exile, and exile is a common theme throughout the film because not only does Elías live in exile for many years, but thousands of Guatemalans were forced to live in exile during the country’s civil war. How did you experience exile and did that have any influence in the documentary?

I do not have the same story that many other people in Guatemala have. I grew up in Costa Rica; in Mexico, too. My experience with exile was not understanding why my dad couldn’t go to Guatemala, because I got to know Guatemala for the first time with my mom, but my dad couldn’t enter. Then my parents separated and in Guatemala there was an agreement just before the peace was signed, allowing refugees and political exiles to return without fearing that something would happen to them. And then my dad came back in 1995, and after [that], well, I would visit my dad once a year.

My first understanding of Guatemala was through exile. In other words, we got together with Guatemalan families, both in Mexico and Costa Rica, and also in Central America. You always hear about the political situation and I remember that when I was little, I asked my dad why he couldn’t go back and he told me it was because of the military. I didn’t quite understand, but it was always there.

I was at the 1996 signing of the Peace Accords in Parque Central de Ciudad de Guatemala. My dad had already been able to come back. It was one of the things that has impacted me the most in my life — to be present in that crowd of thousands and thousands of people. When peace was signed, it was an immense feeling. I had just turned 12 years old, but you could feel a bittersweet feeling. A happiness for the signing, but a latent pain for the number of deaths.

Now, I have lived in Guatemala for 10 years. … And I feel that the story of Elías also reaches me through trying to understand that exile and trying to understand the country. Elías also lived in exile. So I feel that this is why I came to that story and I feel that in a certain way, it’s why Elías also felt a lot of trust.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.