For weeks, prominent scholars and educators, including Ta-Nehisi Coates, Kimberlé Crenshaw and David J. Johns, have called out the College Board for removing contemporary topics and scholarship in Black history from the new Advanced Placement (AP) African American History course being piloted across 60 U.S. schools. Some of these revisions — regarding topics like Black Lives Matter, mass incarceration and reparations — were the same topics of concern outlined in a letter leaked by the Florida Department of Education, which described the College Board’s consistent contact with the DeSantis administration regarding the AP course structure. However, in two separate letters, the College Board denied revising the course on behalf of Gov. Ron DeSantis. The College Board declared instead that the rollout was predetermined, and that Florida’s administration merely sought to claim a nonexistent political victory “by taking credit retroactively for changes we ourselves made but that they never suggested to us.”

Despite the College Board having effectively “set the record straight” in their robust denial of negotiating with Florida’s administration about the course’s content, they have simultaneously made it clear that the revised framework isn’t exactly going anywhere either. This includes downgrading originally required topics like structural racism, racial capitalism, mass incarceration, reparations, intersectionality and Black Lives Matter to now be optional, while introducing research topics like Black conservatism. And while the College Board’s president claims that the removal of works by contemporary Black scholars was because the sources would have been “quite dense” for students, Black educators across the country have a different, more valid theory. Ronda Taylor Bullock, a former teacher and head of the nonprofit anti-racist education center called “we are,” argues that these revisions are the erasure of Black voices and history. The College Board is “cowering to white supremacy — cowering to political power, versus recognizing the academic merits of how the curriculum was from the beginning,” Bullock said.

In fact, cowering to white supremacy and political power may be easy for the College Board because it is an institution forged from racism and eugenics, and designed to preserve higher education for the white, wealthy and privileged. And today, it continues to work exactly the way it was initially intended.

An Instrument of Racism

The College Board is the lucrative nonprofit at the forefront of the college entrance exam establishment and it administers SAT and AP exams. Such exams, especially the SATs, have historically been used by colleges across the country to determine students’ learning capabilities and predict how well they will do in higher education. However, Ibram X. Kendi, Black scholar and author of How to Be an Antiracist, emphasizes that since their inception, standardized tests have been an instrument of racism: “[T]o tell the truth about standardized tests is to tell the story of the eugenicists who created and popularized these tests in the United States more than a century ago.”

In fact, the College Board adopted the SAT test from infamous eugenicist Carl Brigham based on his illusory publication A Study of American Intelligence in 1923, which decried Black people as the lowest on the racial, ethnic and cultural spectrum, and warned of the infiltration of non-white people into white spaces. The resulting exam Brigham developed sought to assess “aptitude for learning” rather than acquired knowledge, which appealed to eugenicists because this aptitude was seen as innate intelligence and thus deeply entrenched with one’s ethnic origins. As a result, aptitude tests could be used to limit the admissions of particular ethnicities deemed “lesser than,” including Black people and Jewish students, especially from Ivy Leagues. Fast-forward to today, the SAT is still accepted as the reliable evaluation for intellectual merit.

However, according to scholars Saul Geiser and Richard Atkinson, it is student GPA (irrespective of the quality of school attended) that is the better predictor of short- and long-term college outcomes. They emphasize that SAT scores actually correlate most with family income and parents’ education — so much so that the supposed predictive power of the SAT signifies the proxy effects of socioeconomic status. High school grades, on the other hand, are less indicative of socioeconomic status, and demonstrate more predictive power of college performance than the SAT even when controls for socioeconomic status are introduced. As a result, prioritizing high school performance over standardized test scores is more equitable, and would expand college opportunities for low-income and marginalized students.

Instead, Black and Latino students bear the brunt of a discriminatory standardized test system, with only 20 percent of Black students and 29 percent of Latino students meeting the benchmark for reading, writing and math portions of the test compared to 57 percent of white students. And these groups bear the brunt for many reasons. In fact, according to scholar Joseph A. Soares, biased test question selection algorithms structurally discriminate against Black people. He argues that, since experimental questions are given to students before the test’s administration, those practice questions where Black students outperform white students are removed so as to maintain the standard bell curve.

Furthermore, the college entry exam business — which includes payments per exam taken, exam prep courses, tutoring, and more — is a multibillion-dollar industry which exploits both parent and student desperation for successful higher education outcomes. As a result, these tests favor white and wealthy test-takers who can not only afford to pay the $60 for each test, but can also spend thousands on prep courses and tutoring, which is one of the only ways to actually improve test scores. This is not an option for poor marginalized folks, who barely have access to nearby SAT testing sites in their areas, let alone money to pay for a weekly SAT tutor.

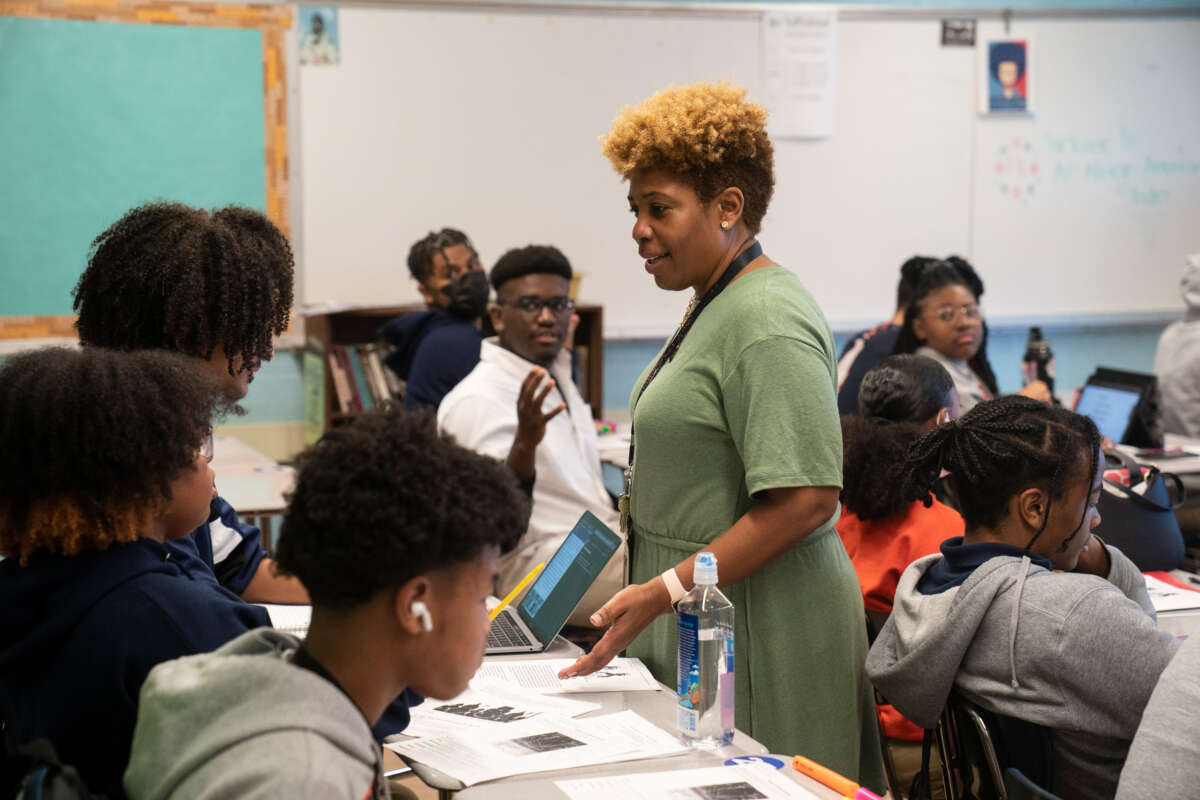

The College Board’s Advanced Placement program — the system offering the new African American studies course — is yet another instrument of white supremacy which disguises inequity under the facade of intellectual exceptionalism. The AP program, which is said to provide advanced educational opportunities for thriving students, persistently grapples with a lack of Black student enrollment. In fact, Black students account for only 9 percent of AP students nationally despite making up 15 percent of the U.S. population. Access to AP classes remain limited for marginalized students whose schools either do not have AP courses available, or because discriminatory practices can particularly hinder Black and Brown students from enrolling in classes when they are available. Such practices include educator bias in recommending students for courses, admission policies that center students’ past achievements over their interests and ambitions and the failure to communicate with marginalized students about AP’s availability to them.

Feeling unwelcome in AP spaces is yet another prominent reason why marginalized folks may be under-enrolled within the courses. Such is the reason why courses like African American history are crucial, as they not only demonstrate a large portion of erased U.S. history, but they also reflect the real, lived experiences of Black students. Courses like these meet marginalized students where they are and create a space through which they can process and articulate such experiences. However, analyzing Black history through the Advanced Placement framework requires a deep reflection of the College Board system itself, which still seems to feel comfortable disappearing Black educational experience even as it establishes a meaningful curriculum.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $41,000 in the next 5 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.