This year cities across the nation erupted in outrage as the stories of police brutality garnered national attention. News coverage of nationwide demonstrations forms a grim mosaic, documenting the trials and tribulations of protesting oppressive institutions: streets flooded with protesters, seas of signs with harrowing messages, street brawls among opposing protesters, and police retaliation, complete with tear gas and rubber bullets. The national conversation surrounding the U.S.’s roots in systemic racism quickly focused on those ubiquitous symbols of the nation’s sordid history which stand tall above city streets across the country: Confederate monuments.

In 2014, Florence, Alabama, nonprofit Project Say Something (PSS), headed up by founder Camille Bennett, launched a movement defined by “making good trouble.” Founded on the basic tenets of education, outreach, truth and inclusivity, the local movement gained traction as the nation’s political climate shifted. In its infancy, the group served as a safe space for small community discussions about race, a haven for the disenfranchised to speak candidly. Gaining more support, PSS expanded its educational mission to incorporate different outreach strategies — creating Black history educational packets for local schools, producing video content highlighting Black voices, circulating archival history on social media and hosting public forums. With 12 executive board members and a Facebook group of over 3,000 followers and growing, the organization continues to flourish under the leadership of educators.

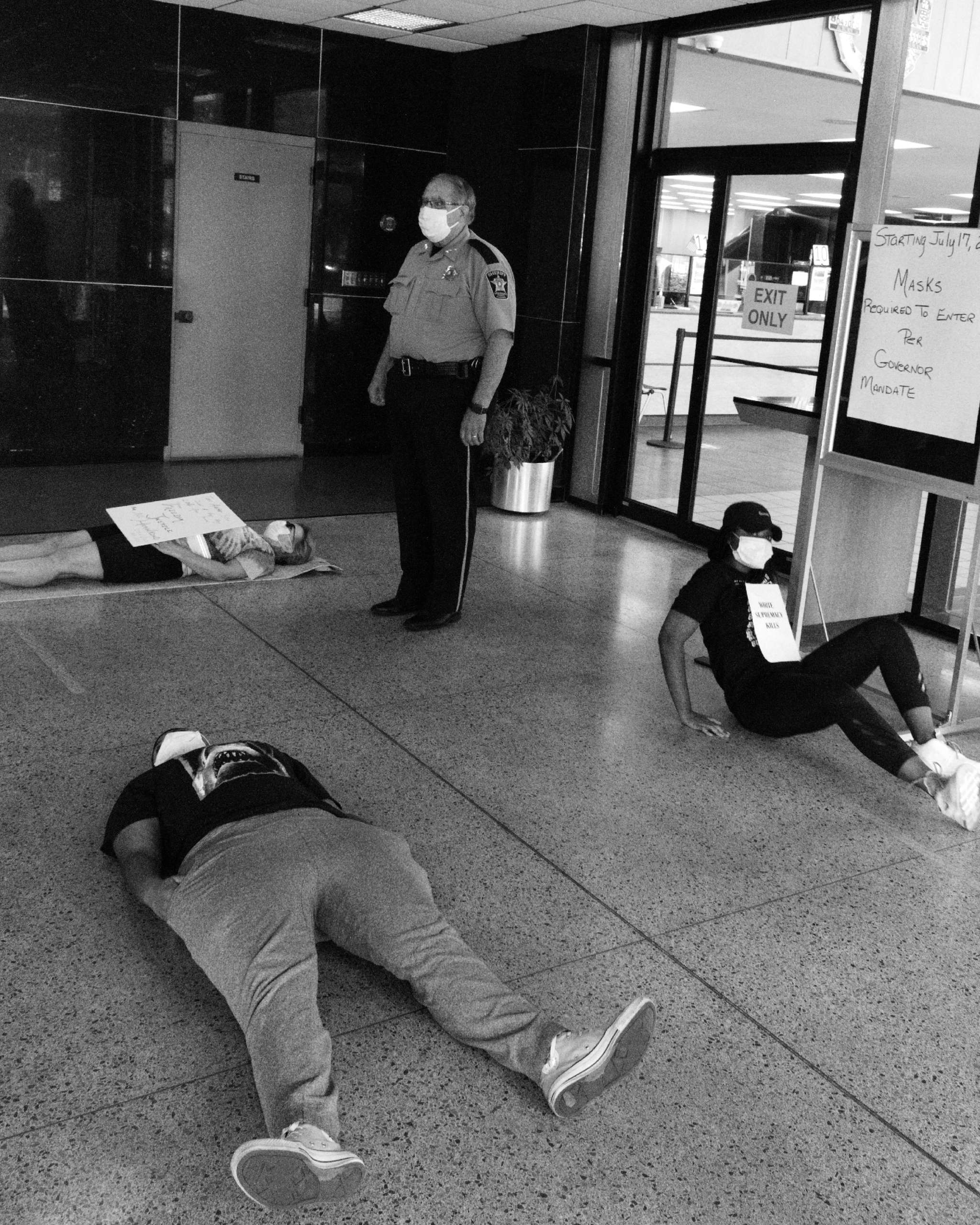

In 2017, PSS began addressing the local Confederate monument, a statue of a nameless soldier erected in 1903 and placed in front of the town’s courthouse. Originally, PSS campaigned for the addition of a statue commemorating the lives of Harriet and Dred Scott, the slave and the civil rights pioneer who sued for his family’s freedom and at one time lived in Florence. With this proposal quickly shot down by local officials, relocation of the monument to one of its originally proposed locations in the soldiers’ cemetery became the goal. The group’s anti-monument demonstrations in front of the courthouse, including a “die-in” at the government office building, quickly became the topic of local chatter after the Lauderdale County Sheriff’s Office forced protesters to vacate the building. Conversations about the monument have served PSS’s primary goal: exposing systematic racism in a town that has long been asleep on the issue.

The small town of Florence has always liked to think of itself as somehow different – many locals view themselves as belonging to a small haven of progressive ideals, family values, Southern hospitality, rich history, a resilient working class and academic ambition. “People have just always gotten along here,” is the familiar mantra of locals who insist Florence is uniquely and miraculously exempt from the racial strife and ignorance that plagues other Southern towns. Perhaps this misconception stems from the fact that Florence is overwhelmingly white, with the Black community accounting for only 20 percent of the overall population, or from the fact that segregation remains an unfortunate reality apparent not only in cultural institutions like churches but also in the city’s layout. Combined, these factors contribute heavily to the erasure of inequality’s impact on local history.

In 1903, H.A. Moody, a Confederate veteran and local doctor, addressed a crowd of thousands at the dedication of Florence’s Confederate monument, a speech that, unlike the monument it commemorates, had hardly seen the light of day until PSS discovered it in a local newspaper archive. This irony wasn’t lost on PSS, which wasted no time in disseminating the text and making the racist history of the statue accessible to locals. Moody’s speech, which was a central part of what the engraving on the base of the statue dubs “appropriate ceremony,” condemned the Northern states’ acceptance of the Black population, whom Moody called the “mongrel” race:

They look upon a Negro as a white man with a colored skin and believe education to be the one thing needful. We of the south know better. No other people know him so well or love him so well, but nowhere here is he accorded social equality. When the highest representative of Northern civilization invites the highest representative of negro civilization to sit at his table as his social equal, he digs a gulf between us too wide and deep for us to go to them or for them to come to us.

Moody’s speech may have remained hidden for years under the dust of ignorance, but today it is read at nearly every PSS event as a reminder of the racist rhetoric’s explicit ties to the monument’s placement and symbology. As PSS leaders recite the speech each night, the words chip away at the already fragile myth of a Florence free from a history of hate.

Against all odds, a statue born from and plagued by division has united a community as Florence residents from all walks of life embrace Project Say Something’s message of inclusivity and find kindred spirits at the protests. “I’ve learned there are a lot more people passionate about Black lives here than I thought,” remarked Dima Rickard.

Protesters who gather beneath the monument for demonstrations each evening work together across boundaries of difference to dismantle the damaging misconception that Florence is immune to inequality.

“How do I respond when people say we don’t have a race issue here? I laugh,” says PSS activist Eartis Bridges. “We’ve gotten so comfortable with racism here that we’re buried.”

Gina Jones Smith echoed Bridges’s sentiment. “Racism has been going on here so long that a lot of us are just going through the motions. I was used to seeing it. This opened my eyes,” she says. “Racism is here and we’re tired. I’m tired.”

Public art exhibitions, children’s nights, performances and sign-making rallies have been among the regular events hosted by the group for the past two months. While hate loomed in the bureaucratic barriers blocking activists from making their voices heard in local government, PSS’s daily programming remained an image of love and unity unsullied by divisiveness.

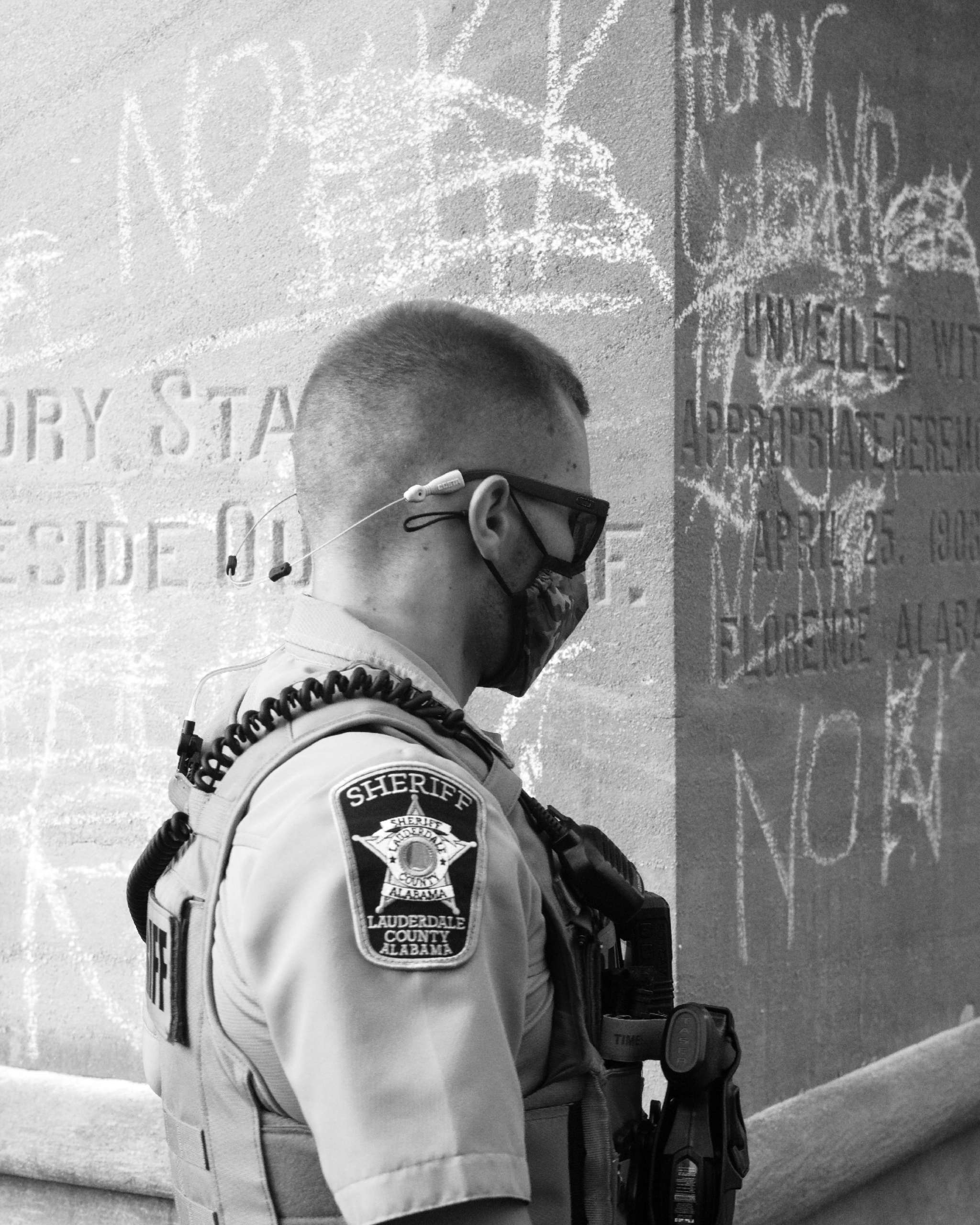

That is, until July 27, 2020, when counterprotesters arrived at the PSS public art event. The PSS crowd broke out in chants as they faced the opposition: “No justice, no peace,” “Black Lives Matter” and “No Trump, no KKK, no racist USA.” Some playfully danced as an antagonist threatened young women with mace. Others merely held up their phones as the counterprotesters hurled obscenities, video documentation becoming a means of self-defense. Tensions mounted as protesters began to write on the monument in chalk, the phrase “no KKK” repeated in bright colors across the marble. Counterprotesters responded with violence, snatching chalk from their hands and shoving protesters.

Police passively observed as a counterprotester swatted a man’s phone out of his hand. Dan Story, the victim of the assault, observed as the assailant spit on another protester. “My family’s gotten threats directly that we should leave before we’re hurt,” he said. “But I never thought it would come to violence. She turned and hit me and called me a ‘disgusting f*****.’ But we don’t sit for injustice. The counterprotesters should educate themselves. We love one another and want equal rights for everyone. We’ll keep coming.” Local police forced protesters to vacate the courthouse plaza.

The following nights, threats increased as outraged conservatives threatened to stake out the protest from the roof with rifles in hand, which local officials dismissed as “differing viewpoints.”

But on July 31, PSS protesters arrived in unprecedented numbers, many from surrounding cities. As the opposition circled the courthouse in trucks, flying Confederate flags and revving engines, PSS protesters quietly turned to face the street, their signs held high as Camille addressed the crowd with a message of peaceful tenacity: “We are about nonviolence. It’s a strategy. They want to criminalize our movement. They want to see you retaliate. Don’t let it happen. Be diligent. Be hypervigilant. But we can’t be patient anymore. We are no longer asking.”

The diverse crowd filled the downtown streets where friendships quickly formed and lessons abounded. “I’m out here because I have kids … and I want better for them,” said Louis Acklin. “Before this, I didn’t know there were this many white folks that agreed with Black folks about these issues. I’m hopeful.”

Beki Ferguson, who spoke about her journey of progression from a conservative upbringing to her newfound embrace of Black Lives Matter allyship, observed that willingness to learn is central to the local movement. “In order to change and grow it takes empathy, and it even takes being curious to learn about how someone different than you lives. When I realize the person I used to be, I get emotional. Because now it seems so obvious. If I could change, so can they.”

“PSS stands for direct action,” said Reemuhlus Bowden. “It’s a unified front here, not just a few people who want it moved. Participation levels here are amazing.”

Emboldened by the previous night’s peaceful defiance of hate, new faces accompanied the familiar ones the following nights. Both evenings ended in dance, and not even counterprotesters’ cries of “KKK all the way” could suppress the protesters’ jubilance and pride. “Even after seeing the opposition, tonight has made me hopeful,” said Tiffany (who did not provide a last name for fear of recent threats). “There are many more people on our side asking for change, and that’s what’s important. I’ve learned how important it is to ask for change. We have to be there for each other.”

Meg Britnell reflected on witnessing counterprotests up close. “Seeing the counterprotesters is overwhelming. It has really shaken me up to see the hate. But it’s just another reason to stand strong,” she said. “My message to the people at home: stand strong and be proud. Be vocal about how you feel.”

At the evening’s close on August 1, Camille announced the event’s end. “Chant to your cars. We’ve gotta clear out!” As the crowd dispersed, chants faded into the night, and the last of the trucks with Confederate regalia disappeared down the streets, Camille’s words echoed with a new significance: “We’ve already made history, y’all.”

PSS assures locals that demonstrations will continue until the monument is moved. For those looking to contribute to the cause, PSS partners with the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area, the Florence-Lauderdale Public Library and the history department at the University of North Alabama to build a local collection of Black history, and implores locals to contribute oral histories and artifacts to their collection. After the monument’s removal, PSS plans to continue partnering with local elementary schools to engage educators and students with local Black history. The group also aims to address the lack of Black representatives in local government and to begin advocating for the allocation of resources to historically Black neighborhoods.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.