Charter schools across the country tapped the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) for what could have been more than $1 billion, according to a preliminary analysis of Treasury Department data.

One network alone, the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP), appears to have pulled somewhere between $28 million and $69 million in taxpayer dollars.

Another network of publicly-funded, privately-run schools, Achievement First, appears to have taken in between $7 million and $17 million in PPP loans. The network also received $3.5 million from a special $65 million federal grant that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos awarded to 10 charter management organizations in April, weeks after the PPP was passed, to “fund the creation and expansion of more than 100 high-quality public charter schools in underserved communities across the country.

Citizens of the World Charter Schools in Los Angeles received $1.7 million of the DeVos grant, and also took between $2 million and $5 million in PPP money.

Mater Academy, Inc., in Miami received $19.2 million of the grant, the most of the field. Three days later, on April 13, it took out more than $1 million in PPP money.

(Another charter school grant program of DeVos’ devising allegedly blew a billion dollars on schools that never opened or shut down after receiving federal money.)

Treasury Department does not disclose specific dollar amounts, but breaks loans into maximum and minimum ranges. Salon’s research did not make clear whether this analysis covered every charter school in the nation, but that seems unlikely. Regardless, the minimum total is roughly $500 million, and t the maximum, the total would appear to exceed $1 billion.

Organizations don’t have to pay back their PPP loans if certain employee retention criteria are met. At least 15 charter schools that reported receiving more than $1 million in payroll protection from the government reported putting that money towards zero jobs. At least seven of the schools left the field blank.

One school, Idaho Arts Charter School, Inc., received between $1 million and $2 million in forgivable relief loans, and reported putting it towards one job.

Charter schools operate in a gray area: They’re publicly funded and are technically public schools, but are privately owned and managed. Most are nonprofits, but some are backed by companies — and both of those categories are eligible for PPP loans.

Though charter schools are taxpayer-funded, they operate under independent boards, and largely beyond public oversight. This raises questions of whether they behave more like public entities or private companies, and has made them the target of congressional Democrats, who cite widespread instances of fraud, corruption and other scandals.

Charters also make appeals under the aegis of “school choice” to students in underserved school districts. Though many charters deliver on promise of higher quality education, others have not, and some of those that do have been accused of siphoning money from public districts that need it the most.

For these reasons, charter schools are seen by some as an existential threat to public education.

The pandemic crisis has underscored the conflict and confusion, as the two sides debate whether charters are trading on their dual status to double-dip into both public and private emergency funds.

When Congress passed the the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March, it allocated $13.5 billion in grants to K-12 schools. Most of that money was intended for public school districts, which share funds with charters.

However, some charters chose to tap into another part of the act, PPP funds, which were set aside to help small businesses and certain nonprofits keep employees on the payroll while they ride out the first few months of the pandemic.

Though public schools share funding with charter schools, traditional public schools were not similarly eligible for PPP money.

Debbie Veney, a spokesperson for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, told CBS Los Angeles that charter schools often eat costs that public schools do not.

“So most people have no idea, for example, that charter schools, which are all public schools, have to actually pay for their facilities, they have to pay rent or a mortgage for the buildings that they’re in,” Veney said. “They have to pay for transportation and they have to take this out of their operating costs.”

Starlee Coleman, CEO of the Texas Public Charter Schools Association, told Salon in an email that charter schools in the state have seen private fundraising drop while incurring unspecified “significant” costs due to the pandemic.

“Almost every school leader that I have talked to has told me they are cutting expenses now to better prepare for the cuts they know they will face after the next legislative session,” she said. “Facing the decision to cut staff positions now in anticipation of coming cuts, PPP loans allowed schools to keep staff on their payroll who weren’t needed while school buildings were closed this spring, like janitors, librarians, and other valued support staff.”

Public schools, which draw solely from taxpayer dollars, do not have that luxury. In Texas, public schools get roughly one-third of their per-student money from the state; charters get all those funds from the state.

“To me, this almost amounts to a double dip. Our charter schools fought tooth-and-nail to get equal funding from the state,” said Colorado State Rep. Jonathan Singer. “When schools across the board are getting cuts, we don’t put charter schools ahead of traditional public schools in Colorado, and we need to either take action as state lawmakers to even the playing field again or they need to have a tougher conversation with the federal government.”

Coleman told Salon she knew that a portion of schools belonging to her association have drawn at least $30 million in PPP funds, but she did not say how many schools she had heard from and had not heard from.

“I know anti-charter interest groups are trying to kick up a storm over charters accessing this money and frankly, I find it laughable,” Coleman said. “We got $30 million collectively in one-time funds while they get $36 BILLION every single year that we can’t access. If there’s something should be reported on, it’s that. Why on earth is it fair for the largely low-income children of color attending public charter schools to receive less school funding?”

Groups such as the national NAACP and the Movement for Black Lives have called for moratoriums on charter school expansion, saying they are harming public schools that need the most support.

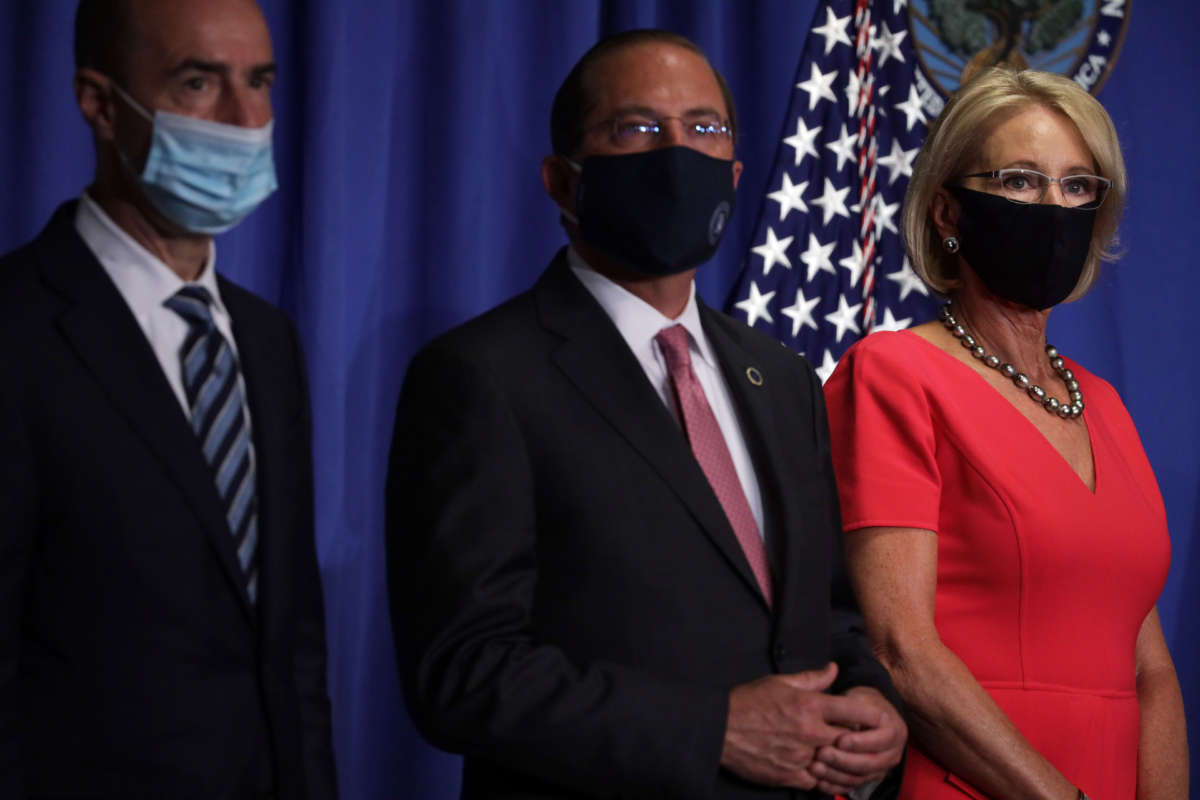

In June, DeVos issued a rule that required public schools to share federal coronavirus relief funds with private and religious schools. The rule could increase funds available to private schools from $127 million to $1.5 billion.

While charter schools could and did draw from other parts of the CARES Act, however, public schools could not.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.