“Academically Adrift”

by Arum and Roksa

(University of Chicago Press 2011)

Bless your hearts, Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, for calling on institutions of higher education to prioritize undergraduate learning. With “Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses,” sociologists Arum and Roksa argue that undergraduate students seem to learn very little in college and that, in fact, they (Arum and Roksa) can show just how much those undergraduates are learning by bringing their own quantitative data set Determinants of College Learning (DCL) – which surveys over 2,300 full-time students at 24 four-year institutions on questions of family background, high school grades and college experiences – together with scores from the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA), a standardized test that analyzes “core outcomes espoused by all of higher education”: critical thinking, problem solving and writing.

Democracy depends upon education that prepares its members for full participation, Arum and Roksa rightly contend. It depends on education to help members develop the critical reasoning and communication on which democratic participation is founded. What's needed then, they say, are “objective measures” of students' learning in relation to their social backgrounds and education experiences. Such measures, Arum and Roksa continue, will hold institutions accountable and will fight the enemy they have named “limited learning,” or more precisely, the “absence of growth in CLA performance” (122).

Arum and Roksa claim to “illuminate the multiple actors contributing to the current state of limited learning on college campuses” (120): students themselves, faculty members, administrators and cultural messages of “college for all” in which the only measure of that access is the college credential that seems to say less and less about college learning. Yet, Arum and Roksa remain unclear as to how those actors are positioned within multiple, intersecting systems of power. They remain unclear as to how schools and formal education itself are positioned within those multiple, intersecting systems of power.

Basil Bernstein (1977) and Paul Willis (1977) have discussed in different ways how education is a major force in structuring student experiences – and how the structure and culture of schools influences how students understand their own identities. Clearly passing over the arguments of Willis and Bernstein, Arum and Roksa call for “as much attention on monitoring and ensuring that undergraduate learning occurs as elementary and secondary school systems are currently being asked to undertake” (55). But the students who arrive on college campuses have more than likely spent up to 12 years in those elementary and secondary classrooms that are being so thoroughly monitored. These undergraduate students' learning experiences and their ideas about learning cannot not have been shaped by these monitoring practices. But any role this might play in Arum's and Roksa's notion of limited learning is never discussed.

Arum and Roksa assume instead that learning is something that can be calculated. And that those calculations exist objectively and without connection to a political context. They assume that skills can be “mastered” completely for participation in “today's complex and competitive world” (31), rather than continuously engaged through the sort of “restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry” that Paulo Freire (1968: 72) envisions. They assume that critical thinking is something that can be “banked” in students by assigning certain numbers of pages of reading and writing and by encouraging students that the most effective means of study is to study alone rather than in dialogue (115-6). Critical thinking as Arum and Roksa present it, is not then about engaging with the world and with others, but rather seems to focus more on efficiently “receiving, filing and storing” of information.

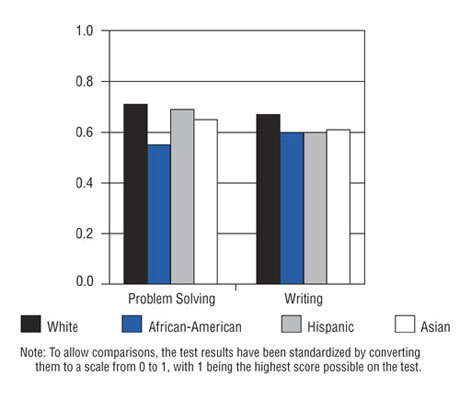

The data that Arum and Roksa provide on CLA scores tabulated by race and ethnicity reveal that the test on which Arum and Roksa base much of their argument is clearly not so neutral. How is it that whiteness can correspond to superior problem solving unless there is something about the way the test conceives of and measures “problem-solving”?

Collegiate Learning Assessment: Mean Scores

(Four-Year College/University Students) 2006

Without acknowledging the political location of their own work and of the sorts of practices called for in it, Arum and Roksa present an idea of higher education stripped of imagination and possibility – stripped of the idea that possible futures do not have to look exactly like what is on display today. I whole-heartedly celebrate Arum's and Roksa's desire to make higher education “meaningful and consequential for students” (55), but “Academically Adrift” is not about engaging students – it rather seems to be about them as containers for holding fixed ideas and as technicians for discrete tasks that some external and allegedly objective entity has decided are definitive measures of critical thought and problem solving.

More meaningful questions about undergraduate learning would likely not ask how to measure critical thinking or how to create an index of academic rigor. More meaningful questions would likely come from a different starting point: questions that look to students' classroom experiences, to their broader social experiences and to the structural contexts and the intersecting systems of power in which those experiences are situated. The classroom can be oppressive or it can be emancipatory. It can be privatized, individualized, compartmentalized – or it can be a place where students question each other and question what they are learning to try to situate it in relation to their world. When the latter is fore grounded, the classroom can be a space of democracy: one where students may come to realize that democratic possibilities don't have to look like the kinds of democracy currently on display.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.