Ute Park, New Mexico – Bill Allen pointed to a north-facing slope of blackened pine and juniper forest. A thin vortex of pale white ash, picked up by a hot morning wind, rose from the black and gray landscape a wildfire left behind.

“It started right there,” said Allen, a rancher and retired hardware store owner.

Igniting May 31 on mountainous terrain, the fire grew quickly. Soon, more than 600 firefighters struggled to protect about 200 homes along the Cimarron River. When the fire was declared over 17 days later, it had burned 36,740 acres of forest and grassland.

Like all wildfires, the Ute Park Fire was dangerous and expensive. But no one died and crews saved every home – thanks in part to a century of hard-won firefighting knowhow.

Science played a vital role in this success story by helping develop the best ways to battle wildfires. But the Trump administration wants to slash federal funding for wildfire science, at a time when forest and brush fires are getting bigger, happening year-round and becoming increasingly erratic.

Federally funded scientists have been seeking new methods and technologies to predict, prepare and respond – critical for safeguarding people and property. They have discovered ways to reduce risks before fires and restore land and waterways afterward. And they explore how fuels, flames, terrain, smoke and weather interact.

Defunding those efforts will endanger lives, researchers told Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting.

“A wildland fire (budget) cut is a human health cut,” said Donald Falk, a University of Arizona professor who has received research funding from some of the federal programs the White House has targeted.

Last week, the latest wildfire tragedy struck Redding, California, where scientists said a super-hot, tornado-like “fire vortex” reached almost 5 miles high. Six people, including two children, have been killed and more than 1,400 homes and buildings have been destroyed so far in the Carr Fire.

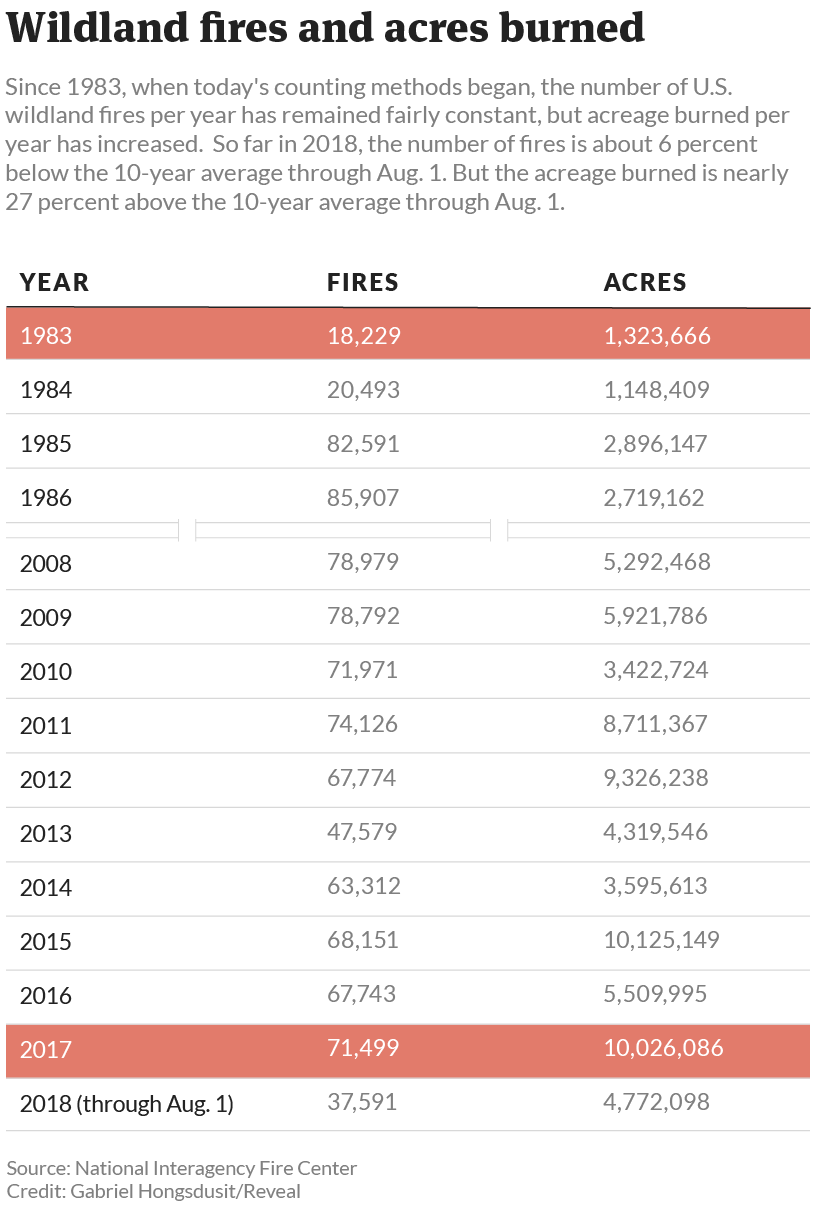

Since 1983, about 72,000 fires have burned the American landscape every year. That number has not grown. But the acreage has – 10 million acres burned last year, which is nearly eight times as much as in 1983.

Nevertheless, fire science funding has been eroding for more than a decade, even before President Donald Trump’s proposed cuts.

Nancy French, a senior research scientist at the Michigan Tech Research Institute who has federal funding, said she is “extremely frustrated, more so than I’ve ever been in my life.”

“You would think with people’s houses burning in California and the concern that we have for air quality that it wouldn’t be hard to find a way to fund someone like me to make sure that my capability is used to help solve some of these problems,” she said.

Interim US Forest Service Chief Vicki Christiansen did not respond to requests for comment about fire research, and the administration’s budget documents contain no explanation for the cuts. But during a Senate hearing in April, she said the administration’s new budget “does reflect hard choices and difficult tradeoffs.”

On-the-Ground Help

Wildland fire science emerges from a small community of physicists, chemists, ecologists, meteorologists and others working for government agencies and universities to understand one of nature’s most violent forces.

The US Forest Service, Interior Department, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Environmental Protection Agency and even the Defense Department have roles. Fire research budgets at these agencies, always small and declining for decades, would take a major hit under Trump’s fiscal 2019 budget.

One proposed cut would eliminate the Joint Fire Science Program, a cooperative venture by the Forest Service and six Interior Department agencies. Even if Congress steps in to fund the program, the financial uncertainty already has forced it to suspend new research proposals for next year.

In the past 10 years alone, the program funded 280 projects by 1,045 scientists at various universities and other institutions, with studies designed to meet the needs of local and state firefighters. This year’s budget is $3 million.

The program’s research “is indeed being utilized in decision-making on the ground,” said University of Arizona research scientist Molly E. Hunter, a science adviser to the program.

Northern New Mexico’s Ute Park Fire, ignited by an unknown cause, is an example of science’s contributions. Homes, mostly vacation retreats, stayed safe during the fire due in part to a fuel reduction plan that Colfax County adopted in 2008 after studies funded by the federal program.

Bea Day, incident commander of a federal-state wildfire team based in New Mexico, said fire and smoke models developed at forestry department research labs – whose budgets are targeted for cuts – helped map her team’s daily strategy to fight the Ute Park Fire. Also in the toolbox are geographical information systems, global positioning systems, satellite observations, air quality monitoring and other science products.

“We utilize all these tools daily,” Day said in an email.

John Cissel, who retired this year as the program’s director, called the Trump administration’s move to end the program a major mistake.

“It seems so short-sighted, especially with a program that’s so meticulously constructed,” he said. He said his decision to retire wasn’t related to Trump’s budget cuts.

The research “has changed the culture and knowledge base around wildfire,’’ said Zander Evans, a scientist and executive director of the nonprofit Forest Stewards Guild, a group of foresters.

The Trump administration has offered no reason for targeting the Joint Fire Science Program. It’s among dozens of areas the White House has proposed slashing or eliminating science funding.

As in the White House’s 2018 budget request, only the Pentagon, Department of Veterans Affairs and NASA would get increased research funding in 2019.

Fire appears only once in the White House’s explanation of its 2019 research and development budget: “In the wake of natural disasters, including a devastating hurricane season and catastrophic forest fires, it is more important than ever to invest in the tools necessary to predict, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from natural disasters.” There’s no mention of wildland fire science.

In the budget proposal, the Forest Service’s spending for all research would drop by 16 percent, or $46 million, from the 2018 level. Interior Department science spending would decrease 21 percent, or $205 million.

Research at NOAA would decline by 26 percent, or $220 million, in the proposed budget. Included would be shutting down NOAA’s Air Resources Laboratory, which studies how smoke, radioactive materials and other human health threats travel in the atmosphere. NOAA also would stop supporting a computer model that predicts smoke travel during a fire.

NOAA spokesman Scott Smullen said in an email that the agency “made tough choices to reduce a number of programs.” He did not respond to a question about how NOAA made the choices.

Scientist and former wildland firefighter Timothy Ingalsbee said the White House won’t save money by cutting fire research. Fires cost more, he said, when science can’t guide prevention and firefighting.

“It makes absolutely no sense,” said Ingalsbee, executive director of the advocacy group Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology. “It doesn’t even make dollars and cents.”

Trees “Burn Like a Blowtorch”

As summer approached, New Mexico’s Cimarron Canyon looked ready for a big fire. The weather was hot. Monsoon rains were weeks off, and a stiff wind stripped away any moisture left after winter brought less than a quarter of normal snowfall.

The grasses, ponderosa pines and pinyon-juniper forest were dry and loaded with years of fuel. Junipers are shrubby, aggressively invasive trees so explosively flammable that firefighters call them “little gasoline bombs” and “gasoline on a stick.”

“They burn like a blowtorch,” said Allen, the rancher.

For years, federal fire research programs have focused on finding the best ways to manage junipers and other fuels. Experts urge people in fire-prone country to remove junipers near their homes.

Following that advice, Allen has been thinning junipers on his 3,400-acre Ute Creek Ranch, including a 20-acre patch that lies south of US Route 64, not far from homes.

“It didn’t burn because we had taken out the junipers,” he said.

As the Ute Park Fire wound down, the Forest Service’s Burned Area Emergency Response program moved in to advise local officials on erosion control. Such work has benefited from research funded by the Joint Fire Science Program. Colfax County also can consult groundbreaking work on social and psychological impacts of wildland fire.

“Cimarrón,” a Spanish word for “wild,” came to describe the geography and history of Colfax County. The Cimarron River, on its way to the Canadian River, has carved dramatic vistas through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Since 1939, about 1 million scouts and leaders have encountered the wild at the Boy Scouts of America’s Philmont Scout Ranch, which covers 140,177 acres around Ute Park and the village of Cimarron. Nearly three-fourths of the Ute Park Fire was on Philmont land. Extreme fire danger has prompted Philmont to close its backcountry activities for the first time in its history.

Cimarron Canyon has seen bigger fires – one in 2002 burned about 92,500 acres – but the Ute Park Fire was closer to the village, coming within a mile. In five hours, it had grown to 1,500 acres; in seven hours, 4,500 acres. It kept growing. The night sky was ablaze.

“It looked like hell was out there,” said Shawn Jeffrey, Cimarron’s village administrator.

Officials ordered Cimarron evacuated for four days. For those who stayed to feed and support fire crews, such as Jeffrey and Village Councilor Laura Gonzales, just breathing was hard. Smoke behavior has been a special interest of the Joint Fire Science Program, including research to improve smoke warnings and learn how smoke harms people.

“The smoke was horrific,” Gonzales said. “You could see when the wind would shift and the fire would rotate.”

Studying a Shifting, Growing Threat

Natural fires can help maintain a healthy ecosystem, but today’s bigger, hotter and longer-lasting fires can kill trees, sterilize soil and burn down entire towns. Bigger fires also make more smoke, which kills about 339,000 people worldwide a year, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

The disturbing trends in wildland fire have several causes. People start 90 percent of wildfires, accidentally or intentionally, and more people are moving to fire-prone places. In addition, decades of suppressing every small fire have left lots of fuel for big ones – the “wildfire paradox.”

Climate change from human activities, chiefly burning fossil fuels, is raising temperatures and contributing to droughts, especially in the West and Southwest. While the Trump administration discounts climate change risks, scientists and firefighters warn that fires in a hotter, drier climate are more unpredictable and might defy today’s strategies.

“There is a great deal of uncertainty,” the University of Arizona’s Hunter said.

Wildland fire science isn’t simple physics or chemistry. Imagine a laboratory, miles wide, where every minute, infinite variables form infinite new combinations – any one of which might kill you.

“Fire science isn’t rocket science; it’s more complicated,” Daniel Godwin, a wildland firefighter and ecologist in Colorado, said in an online discussion of the Joint Fire Science Program’s budget cut.

It takes money, he said, to do the studies that will keep communities and the environment safe under shifting conditions.

Among the Joint Fire Science Program’s most promising current offspring is the Fire and Smoke Model Evaluation Experiment, an eight-year project to improve knowledge of wildfire smoke. Scientists at universities and federal agencies imagined throwing a massive data-collection effort at selected fires, using Lidar, radar, ground monitoring, aircraft, satellites, weather and atmospheric measurements all at once. That has never been done before.

The study seeks to understand the fuels; the smoke’s makeup, behavior and movement; and the chemical changes along the way.

“It’s designed to measure the full spectrum of the fire,” said Tim Brown, a research professor at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada, and an architect of the project.

Such knowledge could vastly improve computer models for firefighting – for example, letting incident managers send a drone ahead of a fire to map fuels with fresh data. Then a model could accurately predict where flames and smoke would go. That could save lives, property and money.

This fall, researchers expected to start their crucial fieldwork, measuring prescribed fires that federal land managers planned anyway but had agreed to schedule to coincide with the experiment. Now, the field study is on hold, and it’s unclear when or whether it will happen. Brown said researchers knew the effort would depend on fickle annual funding but were willing to take the chance.

“There’s a lot of passionate scientists that would still like to carry this forward,” he said. “We’re going to keep trying.”

In an email, Forest Service spokeswoman Dru Fenster said the service had found money to get the researchers for the modeling project some data from other projects. But without the Joint Fire Science Program, she added, the experiment itself is unfunded.

In April, Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington, the ranking Democrat of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, pressed Christiansen, the interim Forest Service chief, on the wisdom of slashing wildfire science as climate change worsens fires. Christiansen didn’t deny climate change’s role or fire science’s importance in her response.

“Our scientific capability is very essential for us to be able to look out ahead and know what we’re facing and then, on the back end of these catastrophic events, how we can best recover the landscape and the communities,” Christiansen said.

The Forest Service’s research budget – including its fire sciences laboratories – already was suffering before Trump. Years of cuts have decimated science staffs, said the University of Arizona’s Falk, who studies fire ecology and resilience in a changing world. For instance, the Joint Fire Science Program used to get about $13 million a year, but took a steep drop in 2011, never to recover. Last fiscal year, it got $6 million; this year, half that.

“There’s no policy being advanced here,” Falk said. “This is 100 percent ideological knee-jerk reaction to any spending.”

Cissel, the program’s retired director, blamed the pre-Trump funding decline on a 40-year federal retreat from science and an Obama-era internal change that had the effect of making fire science compete with the firefighting budget.

“Operational firefighting is reactive,” he said. “Research is proactive. It’s harder to see the proactive, so there’s been a lot of pressure on research budgets.”

Local officials, researchers and foresters in some of the country’s most fire-prone regions – where the quality of fire science can mean life or death – have asked Congress to restore the funding.

In places such as Cimarron, it comes down to knowing how to handle surrounding forests and grasslands so that fire, while inevitable, is also manageable – one of the Joint Fire Science Program’s most vigorous research lines.

“We’ve been working with the local ranchers,” said Jeffrey, the village administrator. “There’s still a lot of fuel out there.”

It also means knowing how a big fire, such as the one in Redding, with its danger and fear, affects people – another area the science program has made a priority. Gonzales, the village councilor in Cimarron, remembers seeing a lot of frightened neighbors.

“We didn’t know – were we going to have to leave?” she said. “It put the scare in a lot of people.”

This story was originally published by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Learn more at revealnews.org and subscribe to the Reveal podcast, produced with PRX, at revealnews.org/podcast.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.