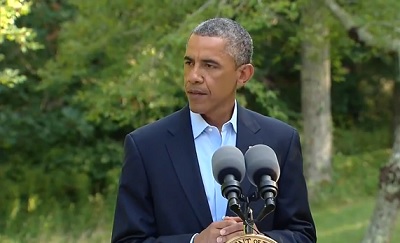

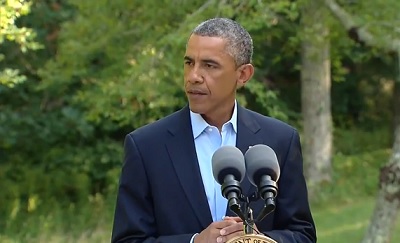

via Whitehouse.gov)” width=”400″ height=”243″ />August 11, 2014: President Obama gives an update on the most recent military and political developments in Iraq. (Screen grab via Whitehouse.gov)On August 11, Iraqi President Fuad Masum named Haider al-Abadi the prime minister. Special forces loyal to incumbent Nouri al-Maliki have deployed in Baghdad, and the stage has been set for yet another episode in the country’s unfolding tragedy of violence. Against this backdrop, US President Barack Obama praised Abadi’s appointment as “a promising step forward.”

via Whitehouse.gov)” width=”400″ height=”243″ />August 11, 2014: President Obama gives an update on the most recent military and political developments in Iraq. (Screen grab via Whitehouse.gov)On August 11, Iraqi President Fuad Masum named Haider al-Abadi the prime minister. Special forces loyal to incumbent Nouri al-Maliki have deployed in Baghdad, and the stage has been set for yet another episode in the country’s unfolding tragedy of violence. Against this backdrop, US President Barack Obama praised Abadi’s appointment as “a promising step forward.”

This is premature and misguided praise for a man that many Iraqis see as another iteration of Maliki, albeit with fresh potential. Yet in a country where continuity is often masked by false promises of change, the nomination of a new prime minister should be met with a critical eye. The corruption at the top of Baghdad’s political hierarchies, and the histories behind its origins, highlight a deeper reality. Politicians like Abadi, who represent – as Maliki did in 2006 – a community of Iraqi elites forced to flee persecution under Saddam Hussein, reinforce the sectarian narrative that has torn Iraq apart.

Surely, Maliki has to go. His divisive policies were largely responsible for sparking the current crisis, alienating Sunni communities, the autonomous Kurdistan region (KRG), and his Shiite allies. Yet he is not the problem, but rather a manifestation of a larger reliance on sectarian narratives used to establish legitimacy for a group of returned exiles without the local knowledge or support necessary to represent the Iraqi citizenry. Since 2003, politics have been sectarianized with visibly disastrous results. This sectarianization of political realities has displaced secular, pluralistic, and local dialogues needed to confront current threats.

To understand the facts of Iraq’s tragedy, it is important to know a bit of history. In 2003, a political system was established based on the idea that Iraqis were divided into categories – Sunni, Shiite, and Kurd. Any Iraqi democratic process had to revolve around these three factions. Shiite opposition groups, who did not hide their sect’s identity, came to power propounding a narrative of victimhood under Saddam. This claim provoked a strong reaction from the Sunni community, which did not know any political organization outside the Baath Party. But these Shiite groups were organized and knew how to play politics.

Nonetheless, few Iraqis knew these new Shiite politicians. Many had been in exile for over 30 years. Names that have since become synonymous with post-invasion Iraq – the Dawa Party, Ahmed Chalabi, the Supreme Council, Ayed Allawi, and of course, Nouri al-Maliki – were all unknown on the capital’s streets. These groups needed to build a constituency quickly, and the easiest way to achieve this goal was by mobilizing a sectarian narrative. They claimed victimhood, pointing out that they had been prevented from ruling their country by the Sunni Baath minority. A new Iraq, they argued, should be constructed in which the majority Shiites would govern. This rhetoric managed to attract followers, and represented the politicization of a Shiite identity that had not previously existed.

A similar process of Sunnification took place as a natural response. Sunni groups reinvented their identities against the new interlopers. The Shiite victimhood that existed under Saddam was replaced by Sunni victimhood after 2003. Radical Islamist groups flourished in this environment, which lacked any inter-communal communication. Ultimately, the abstract idea of community, rather than interaction between these groups and the leaders that supposedly represent them, has emerged to dominate Iraq’s political landscape.

American policy makers adopted this narrative wholeheartedly, grouping the country into Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish blocs. When the Coalition Provisional Authority established the first Iraqi governing body – the Interim Governing Council – they chose members based on their proportion of the Iraqi population.

Today this legacy is all-powerful. Iraq’s new Prime Minister Abadi – assuming he can wrestle control from Maliki – is another representative of the foreign Iraqi community running Baghdad, having lived as an exile in Britain. It is troubling that international leaders are unable to understand the history driving this moment. Their blindness to the roots of Iraq’s political problems illustrates a profound misunderstanding of the ways in which government and governed interact in a country where dialogue is the only viable road to stability.

Yet, instead of studying this story, analysts are turning to the tired ethno-sectarian model for state partition – by which Iraq divides into three semi-autonomous Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish states – that is at the root of the problem. Iraq’s problems are not religious, but rather the result of politicians using religious rhetoric to penetrate the souls of those without the will to look any further.

Stability can only be born from the creation of pluralistic, civilian-led national institutions that affirm the legal equality of each Iraqi. A truly representative army, not what had become essentially a pro-Maliki Shiite militia, is also critical. To confront challenges from foreign cancers like the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Iraq needs armed forces in which all citizens feel invested.

Unfortunately, leaders both in Washington and Baghdad seem unwilling to pursue the hard discussions that could produce these dual necessities. Airstrikes will not mold Iraq into a stable or inclusive state. At the root of this laziness is ignorance of history. Yet, by declaring his support for the new Iraqi prime minister, Obama may have replicated the conditions that produced Maliki in the first place.

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

Last week, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy