“The far right and MAGA adherents are stoking fear and diminishing our students’ freedom to learn and our teachers’ freedom to teach,” says Becky Pringle, the president of the 3 million-member National Education Association (NEA). But Pringle emphasizes that these right-wing attacks are just one part of what is happening in the field of education.

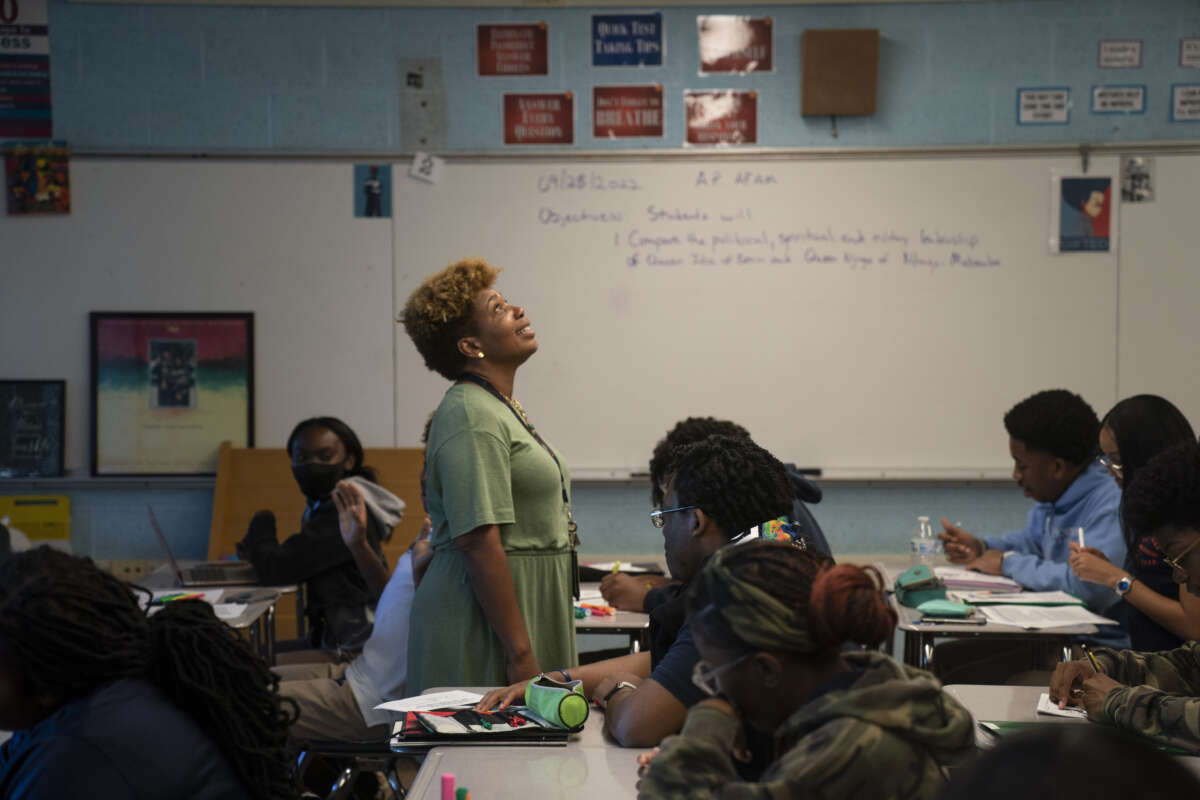

Teachers, administrators and students, she says, are working hard in many parts of the United States to ensure that history, literature and social studies classes engage in meaningful ways with histories of racism, genocide and slavery, while also creating space for studying and celebrating the work of people of color in the U.S.

In fact, even as educators in Florida battle extreme attacks from Gov. Ron DeSantis, educators in more progressive places are doing exciting work to reshape policy and bring an anti-racist, anti-sexist and anti-homophobic perspective into public school classrooms across the country.

“It is important to recognize that people are pushing forward,” Pringle said. “We know the importance of ethnic studies and know that students need to see themselves in the curriculum. Teachers and students understand why it matters to have a racially and culturally inclusive curriculum, and we are continuing to write lesson plans and push legislation to turn back book bans and other limitations on teaching and learning.”

This is not a new position for the NEA, and progressive activists have long promoted the use of diverse classroom materials at every level of study. What’s more, they take inspiration from a 1968 student strike at San Francisco State College (which is now called San Francisco State University) that demanded that the school offer Black, Latinx and Asian history classes to enrolled undergraduates. The successful protest remains the longest student strike in U.S. history — lasting four and a half months — and led to the establishment of several ethnic studies programs on campus.

The momentum that sparked the strike has continued more than a half-century later: In March 2021, California legislators passed a bill to make Black studies a high school graduation requirement for every student beginning in 2030.

Other states — among them Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Vermont — have followed suit and have drafted standards of their own to authorize or mandate instruction that goes beyond Eurocentric knowledge. Most took effect in the 2022-23 academic year.

In Colorado, for example, a 2019 law requires history classes “to include the contributions of diverse groups including LGBTQ, Indigenous, Hispanic, Black, Asian and religious minorities.” And in Nevada, a law passed in 2021 mandates that the contributions of people of color and people with disabilities be incorporated into history, science, arts and humanities classes. For its part, the Illinois legislature passed the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community History (TEAACH) Act in 2021, to require all K-12 social studies classes to include Asian American and Pacific Islander history and challenge stereotypes about Asian identity.

Meanwhile, cities like New York have launched pilot programs that zero-in on LGBTQIA+, Black, and Asian American and Pacific Islander history. Rita Joseph, chair of the New York City Council Education Committee, says that the Council feels a sense of urgency to increase diversity and desegregate public schools throughout the five boroughs. “We’re also trying to recruit Black male teachers and other teachers of color and are working to ensure that classrooms and libraries have varied books — with boys who want to be mermaids, girls in hijab, and immigrants from Africa — so that every student knows that they are seen and heard,” Joseph told Truthout.

The rationale for this has been well established.

Thirty-three years ago, the Saturday Review printed an essay called “The All-White World of Children’s Books.” In it, author Nancy Larrick wrote that when children do not see themselves reflected in the stories they read, or in the curriculum they’re taught, “they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued” by society.

Larrick’s message to educators was unambiguous: “Our classrooms need to be places where all the children from all the cultures that make up the salad bowl of American society” can find their reflections. The end result, she wrote, will be a “better understanding of difference and a respect for diversity.”

NEA researchers have reached the same conclusion. A 2020 report found that “interdisciplinary ethnic studies, or the study of the social, political, economic, and historical perspectives of our nation’s diverse racial and ethnic groups, helps foster cross-cultural understanding among both students of color and white students.”

In addition, the researchers reported that students who enrolled in ethnic studies were more academically engaged, developed a stronger sense of self, and graduated at higher rates than students who did not.

Students also benefit when diverse perspectives are brought into non-ethnic studies classes.

Maddox Lima, a first-year student at Skidmore College, recalls that when he was in 10th grade at North Kingstown High School, a public school in Rhode Island, his English teacher had the class read The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. “African American history was woven into our discussions,” he told Truthout. “We learned about the U.S. after the Civil War, and we looked at the racial constructions that were set up, the way society was organized. The class was interdisciplinary and brought history and social studies into English.”

Lima says that he loved the course and was disappointed that this approach was not embraced by other teachers. “Even in World Literature, we just read the assigned texts without examining what they said about the dominant culture or the ways race and gender played out,” he said.

Others public schools follow a different model.

Susan Wu, a 9th grader at Fort Hamilton High School in Brooklyn, New York, told Truthout that non-European people and events are highlighted in just about every class she’s taking, from music, to history, to English. “It makes me feel included as an Asian girl,” she said. “My U.S. history class taught us about Hawaiian culture, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and how Islam has influenced America. The books we’ve read are really interesting, too.”

But Wu says she knows that many other students do not share this experience, since many schools do not prioritize learning about different cultures; even within a school, she adds, instruction can vary widely from teacher to teacher.

A Patchwork Nation

Wayne Au, a professor of education at the University of Washington-Bothell and an editor at Rethinking Schools, a 37-year-old quarterly publication devoted to promoting social justice, told Truthout that the right-wing offensive against diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives; attacks on queer kids; and book bans are happening on both the state and district levels.

“There is a divide between places where teachers have the leeway to teach the truth about history and culture, and places where teachers can’t do this even if they want to,” Au said. “People have been physically threatened, so there is not always the space for teachers to do anti-racist education. But when states pass legislation that supports multicultural learning, it gives teachers room to create curricula. It also gives them the official backing to do work they know is for the common good. Of course, developing curricula can be complicated and state-approved materials are often safer than we want, but they’re a start.”

Moreover, teachers can always supplement what the state offers.

The Zinn Education Project, he explains, has helped set up more than 200 teacher study groups in 38 states since 2020. More than 1,000 educators have enrolled. Coursework teaches history they might never have learned and helps them formulate lessons for their students; a 2018 book, Teaching for Black Lives grounds the program. Among the topics covered: COINTELPRO, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the 1921 Tulsa race riots, the school-to-prison pipeline, the Black Panther Party, and other subjects that are typically ignored or given scant mention in mainstream textbooks.

“The study groups also feature the teaching of Black joy,” Au said. “We want students to feel good about their hair and bodies. Furthermore, we’re showing them models of activism and resistance so that students will understand that they can act and do things differently than their elders.”

Nirva Rebecca LaFortune, a parent and former Providence, Rhode Island, legislator, agrees that these are essential messages. “History should always be the history of empowerment,” she says. She added that “lessons on Black history should not be restricted to the month of February” or focus exclusively on Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and George Washington Carver, but should include Rosewood, the town that was burned to the ground in 1923 by white racists, alongside other egregious chapters in U.S. history.

Rann Miller, author of Resistance Stories from Black History for Kids and creator of the Urban Education Mixtape blog, has taught and run DEI programs in New Jersey for more than a decade. He told Truthout that his state has passed several laws to mandate the teaching of African American and LGBTQIA+ history. “Our governor, Phil Murphy, has said that he wants New Jersey to be the anti-Florida. It helps to have lawmakers who understand the urgency of this moment for racial and gender justice, especially when it comes to policies around education.”

Miller said New Jersey takes its responsibility to teach every child seriously and sponsors a summer institute to train faculty in best practices for supporting equity, racial justice, gender identity and sexuality in class.

Similar training programs are underway throughout the country — for both new and experienced teachers.

“We have to ensure that teacher education programs orient students so that they can teach the complexities of history, race and culture, and understand that their students are multicultural,” Au said. “Most teacher training programs are progressive, but it can be hard when a student graduates and then goes to a district where they are expected to comply with a conservative school culture.”

That’s where the support of progressive colleagues comes into play — whether through publications like Rethinking Schools, or through study groups, conference attendance, or networks of like-minded instructors.

Post-graduate training is also key, even for seasoned teachers. “In my state,” Au says, “There is a mandate that schools teach Since Time Immemorial: Tribal Sovereignty in Washington State,” a curriculum that was created in 2015 by leaders of 29 tribes.

Although the curriculum has not yet been fully implemented across all grade levels, online trainings have helped non-Native educators become more knowledgeable and comfortable in presenting the lessons offered. In addition to learning concrete information about different tribal histories and cultures, the training addresses the social and emotional impact of Native inclusion on young Indigenous students. “Integrating indigenous history and knowledge can be a matter of life and death for Native youth,“ an article in Crosscut News reports, helping to derail the high suicide rate among Native kids who feel disconnected and undervalued by mainstream educational programs.

Scott Abbott, assistant director of the Delaware Center for Civics Education, calls equity the centerpiece of education. That said, he adds that ideological agreement alone is insufficient to create schools where every kid can thrive and grow. “Funding matters,” he told Truthout. “For states and districts to develop materials they have to be able to purchase supplies.” Additionally, funding may be needed for ongoing professional development or coaching to help teachers modify existing curricula and teach new lessons.

“The fact that efforts to diversify and expand multicultural and ethnic studies coursework is happening now — at the same time that some states are cutting diversity funding, banning books, and restricting how history and literature can be taught — is important,” Abbott says. “Inclusive curricula that tackle complex historical realities help students analyze the past, pose questions for inquiry and help them make sense of the world. But this should be happening everywhere. It should not be a patchwork.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.