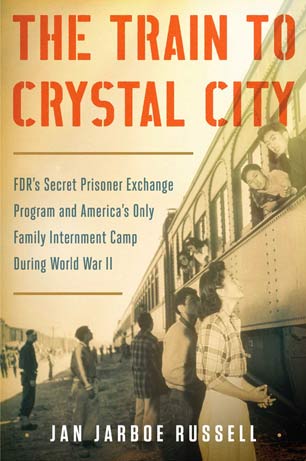

The Train to Crystal City: FDR’s Secret Prisoner Exchange Program and America’s Only Family Internment Camp During World War II, by Jan Jarboe Russell, Scribner, 400 pages, $30.00 hardcover [January 20, 2015 release date].

Like many things in life, journalist Jan Jarboe Russell learned about the World War II-era Crystal City Internment Camp by chance. It was 40 years ago and she was a college student. Her professor, the late Alan Taniguchi, told her that his family had ended up in Texas because of a camp.

“Church camp?” she asked.

“Not exactly,” he replied, going on to explain that he and his parents had been considered “enemy aliens” during World War II. They had been detained, he told her, as part of a sweep of men and women the FBI considered suspect because of their ethnicity.

Russell had known some of this. She knew, for example, that 120,000 Japanese people, 62 percent of them US citizens, had been rounded up after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and held in 10 camps in Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. She also knew that this was done at the behest of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and that Executive Order 9066 allowed the US government to hold suspects without charges or trial, and seize their property – including homes and businesses – without warning or due process.

But Crystal City? Why, Russell wondered, was it never mentioned in accounts of wartime security efforts? Why did so few people know of the 290-acre outpost that held German, Italian and Japanese citizens, plus Japanese nationals who had been living in 13 Latin American countries, as well as their spouses and US-Latin American-born children, for the duration of the war? And why were some repatriated to their “homelands,” in some cases “homelands” they’d never seen because of their birth on US or Latin American soil? Lastly, since some of Crystal City’s prisoners were part of a secret exchange program, whom were they exchanged for?

If it sounds like a mystery writ large, it was, and Russell set out to unravel the many strands of public policy that established and maintained the camp for six years, from 1942 to 1948. Along the way, she interviewed dozens of people interned in Crystal City.

The book focuses on three families and by meticulously exploring their experiences, Russell paints a vivid picture of day-to-day life behind the barbed wire.

It’s a gripping, horrifying and fascinating read.

The Eiserloh family is the first one profiled. Matthias and Johanna Eiserloh had immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1923 and settled in Strongville, Ohio. They were legal residents and, beginning in 1930, Johanna gave birth to four US-citizen children.

Although they did not know it, prior to US involvement in the war, the FBI was paying close attention to German immigrants, investigating suspected members of pro-Nazi organizations as well as anyone they thought might pose a security risk in the event of war. These preparations meant that immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI was ready to spring into action and agents quickly arrested an estimated “2,000 Japanese and German immigrants on the west and east coasts,” Russell writes. “Fourteen days later, the FBI held under arrest 1,430 Japanese, 215 Italians and 1,153 Germans in the continental United States and Hawaii.”

Inflammatory news coverage further stoked fears of “enemies among us,” and in short order, many residents of Strongville’s German enclave stopped speaking their first language in public. “Agents came to town to interview their non-German neighbors,” Russell writes. “As had happened during World War I, anti-German sentiment was everywhere. Sauerkraut became ‘liberty cabbage’ and hamburgers were renamed ‘Salisbury steak.’ In nearby Cleveland, the city orchestra even stopped performing works of Beethoven.”

Matthias told his wife and kids that some of his co-workers were giving him the stink eye and he worried aloud about what might happen. He was smart to be fearful: On January 8, 1942, armed FBI agents showed up at their home, searched it and confiscated letters, photos, paintings and books. Matthias was ultimately ordered into custodial detention. This, Russell writes, “meant that he could be held in prison indefinitely. The word arrest was not used. Eiserloh had no rights under US law. He was not allowed a lawyer. No charges were filed, and he would never be convicted of any crime. Yet from that moment on, he was officially branded as a dangerous enemy alien.”

Although the family was eventually reunited in Crystal City – and later repatriated to Germany – Russell offers a harrowing description of the family’s ordeal. “Eiserloh was an enemy by virtue of his German citizenship,” she writes, “and the FBI viewed him as a security threat . . . Johanna and his American-born children were collateral damage.” The Eiserlohs were not alone. During the war, Roosevelt interned 31,275 “enemy aliens” deemed suitable for possible exchange: five Bulgarians; 10,905 Germans; 52 Hungarians; 3,278 Italians; 16,849 Japanese; 25 Romanians; and 161 listed simply as “others.”

Strikingly, Russell continues, scholars have estimated that about 3 percent of the German internees, most of them from Latin America, were vocal supporters of Nazi ideology. The rest? They may have been quiet supporters. Or not.

Matthias was separated from his family for 18 months during which time Johanna and the kids lapsed into poverty, losing their home and taking cover in the cramped basement of a relative. As for Matthias, he reportedly became despondent about his situation and agreed that he and his family would return to Germany. Nonetheless, he begged the authorities to reunite his family in Crystal City pending deportation. His wish was granted.

Russell also profiles the Utsushigawa family. American-born Sumi and her Japanese-born parents were living in the Little Tokyo section of Los Angeles when war broke out. “Within two hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, FBI agents swarmed through the narrow streets of Little Tokyo and placed Japanese leaders in handcuffs, leading them away from their friends and families,” she writes. Several days later, Japanese branch banks in Little Tokyo were closed. Anyone who had been born in Japan had his or her accounts frozen, leaving people like the Utsushigawas penniless. Before Pearl Harbor, Tom, the father, was a successful commercial photographer, but his career offered scant protection. On March 13, 1942, the FBI took Tom away; like the Eiserlohs, the family was reunited in Crystal City after a year and a half apart. They were eventually deported to Japan in a September 1943 exchange between approximately 1,330 Japanese civilians and an equal number of US diplomats, businesspeople, missionaries and journalists who had been held prisoner in Japan. An earlier agreement, in June 1942, had returned 250 government officials and 2,500 US civilians. All told, six prisoner exchanges took place during the war; one involved the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp run by the Nazis.

In fact, the third story in The Train to Crystal City introduces Irene Hasenberg, an “exchange Jew” who left Bergen-Belsen as part of a program that swapped them for German prisoners from Crystal City, Texas. Her story reads like something out of a spy thriller. As Russell tells it, Irene and her family – two parents and a brother – had somehow obtained false passports from Ecuador, a bit of luck that gave them a way out. German-born, the Hasenbergs were in Holland when the war began. Like the famous Frank family, they debated going into hiding, but opted not to. They were subsequently sent to the Westerbork Training Camp in the Netherlands. While there, their Ecuadoran passports protected them from being transported to Auschwitz. Instead, they were sent to Bergen-Belsen where they remained for 11 excruciating months. Although Irene’s dad did not live to see it, Irene, her mother and brother were eventually placed on an exchange list. Later, when illness kept her mother and brother from leaving at the assigned time, Irene traveled alone, going first to Algeria, and later journeying to the United States.

As for the repatriation, the reality of returning to Japan and Germany was beyond grim. Both the Eiserloh and Utsushigawa families encountered horrible conditions in their homelands: bombed out cities, food and housing shortages, rampant disease, and an inability to find work, at least initially. While all of the US-born children mentioned in the book returned to the United States, not surprisingly, each was scarred by both the repatriation and their time in Crystal City.

That said, it is important to note that Crystal City staffers tried to make the camp reasonably comfortable. There were three schools – offering lessons in English, German and Japanese – and families could choose where to send their kids. In addition, the camp provided ample food and shelter, and prisoners had access to social halls, a gigantic swimming pool and other diversions. Nonetheless, residents could not come and go as they pleased. The loss of freedom, Russell writes, meant that in Crystal City, “more than 6,000 American citizens and immigrants from other countries – ordinary people – endured confinement because of an overzealous government, widespread public fear of traitors, and a game of barter: our internees in America for their internees in Axis countries. The heart of the problem was found in the Alien Enemies Act. Anyone of German, Japanese or Italian ancestry, regardless of citizenship, was viewed as a perceived enemy.”

Russell’s reporting shines a bright light on the indignities suffered nearly 70 years ago. While she does not connect the dots to the 1,100 deportations a day that are currently being carried out under President Obama’s leadership, The Train to Crystal City is an eye-opening and moving look at the personal and political impact of racist policies.

Many of those who survived the atrocities of World War II have died and others are now quite old. But those who were held in Crystal City or other detention camps vividly recall their confinement and some are still working to make it mean something. Irene Hasenberg and five other Jewish Holocaust survivors, for example, meet regularly with a group of Arab women in what Russell says is an effort to bridge their social, political and religious differences. “It’s a work of peace,” Hasenberg told Russell. “We so-called enemies meet and listen to one another. How else can we learn from our mistakes?”

How else, indeed.

5 Days Left: All gifts to Truthout now matched!

From now until the end of the year, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $50,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just 5 days left to raise $50,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!