WORLD EXCLUSIVE: Meet the brother of the first high-value detainee; he came to the US to pursue the American dream, spent two years in an immigration jail following the 9/11 attacks and was then recruited by the FBI to spy on Muslims.

This investigative report is also available for download as an ebook.

Hesham opened the envelope at the bar, expecting a green card. Instead, it was a subpoena from a federal prosecutor, which would force him to testify—against his brother.

He thought about fleeing to Norway or Poland with his wife and daughter. But it would be much easier to cross the border into Canada in his Cadillac Escalade and avoid the hassle of airport security and the possibility that his name would pop up on the no-fly list.  Hesham Abu Zubaidah speaking to Truthout in November 2011 at his home in Florida. (Photo: Lance Page / Truthout)In Canada, he could start over again. Raise farm animals or something. Change his name. Never look back. Hesham had played this fantasy out in his head dozens of times since he had quit working as a confidential informant for the FBI.

Hesham Abu Zubaidah speaking to Truthout in November 2011 at his home in Florida. (Photo: Lance Page / Truthout)In Canada, he could start over again. Raise farm animals or something. Change his name. Never look back. Hesham had played this fantasy out in his head dozens of times since he had quit working as a confidential informant for the FBI.

“This is what you wanted from me all along, isn’t it?” Hesham asked the FBI agent who handed him the envelope. “You guys used me.”

When he’d been living in Portland, Oregon, Hesham had agreed to infiltrate mosques and spy on other Muslims because his FBI handler led him to believe she could help him obtain a green card. She didn’t, and he cut off contact with the agency when he moved to Central Florida. But they had found him again.

“No way,” Hesham said.

“You don’t have a choice,” the agent told Hesham. “Testify or go back to jail.”

Hesham stared at the agent. He didn’t say a word. His eyes started to twitch, which happens whenever he gets angry. He stood up, pulled his wallet out of his back pocket, placed a $20 bill under his whiskey glass and walked outside to light a cigarette. He paced the parking lot, cursing his brother’s name. Two FBI agents and a special agent with the US Army’s Criminal Investigation Command watched him from a distance.

Hesham flicked his cigarette butt and walked back toward them. Going back to jail wasn’t an option. He was afraid he would never get out and would never see his wife and daughter again.

“When do I need to do this?” Hesham asked the agents.

“Probably in a few weeks,” the Army special agent said. “We’ll either stop by or call you.”

Hesham got into his car and tore out of the parking lot, his tires screeching. He felt weak, trapped and ashamed. Hesham hoped his brother would forgive him for ratting him out.

Hesham Mohamed Hussain Abu Zubaidah is the younger brother of Zayn al-Abidin Mohamed Husayn, better known to the world as the high-value Guantanamo detainee “Abu Zubaidah,” whom the US government has for more than a decade claimed was “one of the highest-ranking members of the al-Qaeda terrorist organization” and “involved in every major terrorist operation carried out by al-Qaeda,” including the 9/11 attacks [1].

Research I was conducting on the accused terrorist led me to Hesham. I had stumbled across a three-year-old comment on a blog post left by someone who identified himself as Hesham.

“Yes that is my brother and I live in Oregon,” the commenter said. “Do you think I should have been locked away for 2 years with no charges for a [sic] act of a sibling? I am the younger brother of Zayn and I live in the USA. Tell me what you think.”

A search of his name on Google turned up only 28 results, including another comment posted by a person using Hesham’s name, as well as one by a person identifying herself as Hesham’s wife. Who was Hesham, and why hadn’t we heard of him before?

It struck me then that everything we knew about Hesham’s famous brother was based on what the government had told us. His name appears in the infamous August 6, 2001, Presidential Daily Briefing, which warned President George W. Bush that Osama bin Laden was determined to attack the United States. He was the first major terrorist captured after 9/11 and whisked away to the CIA’s top-secret black site prisons. He has been publicly described by top Bush administration officials as Bin Laden’s “lieutenant” and the number-two or -three person in al-Qaeda. He is the captive around whom the torture program was built, and he was the first prisoner to be waterboarded.

I had intended to write a profile of Abu Zubaidah, and I hoped Hesham could fill in details about his brother’s life and alleged terrorist activities. But what I discovered was that Hesham had his own important story to tell.

The Zubaidah brothers have not seen each other in more than two decades. They have lived utterly separate lives. One brother was, according to the government’s narrative, dead-set on destroying America, while the other was determined to pursue the American dream.

Hesham said the first time he learned that his brother had been involved in any alleged terrorist activities was immediately after 9/11, when FBI agents showed up at his apartment in Portland with a set of photographs they asked him to identify.

“I didn’t believe it,” Hesham said when he first learned of the allegations that his brother was involved in the planning of the 9/11. “I did not recognize the person in the pictures the FBI showed me. The person in the photographs had a beard and a mustache. My brother used to shave his mustache all the time. They had pictures where he had blue eyes, blond hair and green hair. The person just didn’t look anything like the person I grew up with. I told the FBI, ‘The guy you’re talking about, I don’t know that guy.'”

Hesham says he has been paying a price ever since for having the same name as the suspect in the pictures.

Why didn’t the FBI speak to Hesham before 9/11? It would seem a simple visit to the sibling of the person designated as a notorious al-Qaeda terrorist would be standard law enforcement procedure. But it wasn’t. Rather than interview Hesham, the FBI instead secretly spoke to his wife, about three weeks before 9/11.

John Kiriakou, the former CIA officer who helped lead the operation that resulted in Zubaidah’s capture on March 28, 2002, said he could not believe Zubaidah had a brother living in the United States at a time when the intelligence community was trying to track down and capture Zubaidah.

“That’s just stunning to me,” Kiriakou said in an interview last summer. “Before the raid, our team was trying to find people who knew Zubaidah. We heard he had a brother or a relative in Paris and tried to track him down, but that didn’t pan out. Had I known Zubaidah had a brother in the US, I would have demanded headquarters get the FBI to make immediate contact with him and squeeze as much info out of him as we could about his brother.”

SIDEBAR: “So Then the FBI Sent an Agent Out to Check Up on My FOIA Request on Hesham”

***

Hesham is a Palestinian who was born in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on April 28, 1976. He is the sixth of ten children – five boys and five girls – born to Malika and Mohamed Abu Zubaidah, a prominent and well-respected businessman and teacher of Arabic. Hesham is five years younger than Zayn, who was given the nickname “Hani” by his father.

Hesham now often refers to Hani as “that guy.”

Mohamed owned a number of businesses, including small supermarkets and barber shops, and the family eventually moved into a house that would be considered a mansion by US standards.

The Zubaidahs were a close-knit family. They vacationed together in Jordan and Jerusalem, and once a month, they crowded around their television set to eat popcorn and watch movies Mohamed brought home.

But Hesham had a rough childhood. He was diagnosed with testicular cancer just as he entered high school and was bedridden for three years. He slipped into a coma for several months. Hesham’s doctors did not believe he would survive. His father secured top-notch treatment in one of the Saudi royal hospitals, where Hesham underwent intensive chemotherapy treatment that saved him.

By the time Hesham was deemed cancer free, he had lost some of his memory. The cancer scarred him in other ways, too.

“I became depressed,” Hesham said. “One day, I just woke up and I didn’t even know where I was or what happened. All of my friends were gone. My brothers and sisters were gone. They were grown up and went off to college, and I still felt like a child.”

Hesham’s father wanted his children to have a better life than he had growing up in Palestine, and he emphasized the importance of education. He financed all of his children’s college studies, and he personally taught them reading and writing. Hani was sent abroad to study computers and engineering in India.

Hesham’s memories of Hani are foggy. But there are several that stand out. He remembered his brother as always wearing blue jeans, which annoyed his father, who wanted his children to fit in and dress in traditional Saudi attire. Hani was also a budding musician who played the keyboards and protected Hesham from neighborhood bullies.

“Hani was a good guy,” Hesham said. “He was the guy I could reach out to for help. He was the guy I could get an opinion from about my father. He was outgoing and a lot of fun to be around. I remember when I was a kid, he took me for a ride in his car to the beach, and we had a barbecue with his friends. When the older kids I was playing soccer with started to push me around, Hani came over and stood up to them. Hani told me that I can’t let anyone push me around and that I have to stand up for myself and fight.”

Hesham also remembers Hani as being somewhat of a “womanizer.” Hesham recalled a time when his family was living in a split-level house. He says he must have been around 10 years old, and another family moved in upstairs.

“There was a cute girl who moved in,” Hesham said, “And one day she was home alone, and Hani told me to go to the store to get him a pack of cigarettes. He was trying to make it with the girl. I saw him smiling from the window as I rode away on my bicycle. He did that a lot.”

Hesham added that Hani never displayed any signs of religious extremism growing up.

“That guy was never religious,” Hesham said. “He liked to drink and smoke and play music and have a good time.”

Hesham was around 11 or 12 years-old when Hani graduated high-school and left Saudi Arabia to attend college. That was the last time Hesham saw Hani.

According to WikiLeaks files, rather than attend university in the late 1980s, Hani trained at a camp affiliated with al-Qaeda, and in 1990-1991, travelled to Afghanistan for additional training. By 1992, Hani had suffered a shrapnel wound to the head while fighting on the front lines of a civil war in Afghanistan and lost his memory and the ability to speak for about a year.

Hesham and Hani were the siblings who butted heads with their father over their school grades and their career paths. Mohamed was strict and had clear ideas about what he expected from his children.

“Me and Hani were the black sheep of the family,” Hesham said. “All of my other brothers and sisters are doctors, professors, psychologists. I could not compete with them. I tried to compete on their level but I couldn’t.”

Hesham’s high school grades were merely adequate. He was four years older than the other students in his class; it was embarrassing, he said.

Hesham took an interest in architecture and auto mechanics. He was good with his hands, he said, and one time built a go-cart out of wood. He spent two years in college in Jordan but he couldn’t hack it, and when he told his father, his funds were cut off. He ended up in a refugee camp, penniless. His mother traveled to Jordan and brought him back to Saudi Arabia, but he got into serious trouble when he was pulled over by Saudi police for traveling in a car with a female passenger to whom he was not married. He received 40 lashes on his back with bamboo for the infraction. A friend of Hesham’s who was also a passenger, Bashar Jaber, was also whipped.

“I wanted to get the hell out of Saudi Arabia,” Hesham said. “I hate the religion and I hate the politics. I wanted out.”

While his friend and siblings were excelling in college and their professions, Hesham struggled and felt like an outcast.

He went to work for his brother-in-law’s waste management company, but when his family tried to arrange a marriage to his brother-in-law’s sister, he refused. He quit. Bashar told him he should consider moving to the United States.

“Bashar said I could get a job in a gas station for seven bucks an hour,” Hesham said. “He went to visit America and said I could live the American dream and build something for myself and get married and get away from my father. I was fighting to be myself, and I could not do that in Saudi Arabia because my father passed judgment on me.”

Hesham liked the idea that in the United States he might eventually become a US citizen; citizenship was something his family could not attain in Saudi Arabia because they were Palestinians.

So, one of Hesham’s older brothers took him to the US Embassy in Saudi Arabia.

“My oldest brother Maher [who is now a renowned heart surgeon in Saudi Arabia] came with me to the embassy,” Hesham said. “He told the woman there who handled the visas, ‘We sent him to Jordan and he didn’t do any good there; then we sent him to work at his brother-in-law’s but he just fucked around for a few months. Now he wants to go to America. You know what will happen? He’ll stay there for a few months and learn some English and then call us to come home.'”

The woman at the embassy granted Hesham a student visa on July 15, 1998, with the understanding that he would attend an English language school in Melbourne, Florida.

Hesham sold his car and bought a plane ticket bound for New York City. It was cheaper than purchasing a direct ticket to Florida, and he thought he could just fly when he landed. Before he headed for the airport, he had a few last words for his father.

“I told him when I get to America, I will make it and I will be rich and I will be a citizen,” he said. “My father said back that no one would ever accept me.”

The American Dream

Hesham arrived in the United States on July 26, 1998; he was 22.

He discovered that he did not have enough money to purchase a plane ticket to Florida. It would have cost thousands of dollars because he had failed to book the ticket in advance. So, he bought a train ticket and traveled to Dallas, Texas, to stay with some distant relatives. Hesham’s time in Dallas was short-lived. His cousin told him that it would prove difficult for him to “try and make it” in Texas due to strict immigration laws, and advised him to travel to Chicago and stay with another cousin who was studying to be a pharmacist.

In Chicago, Hesham took jobs pumping gas and as a busboy in a Jewish restaurant and shared an apartment with his cousin and two other men. He was later promoted to waiter. His student visa did not authorize him to work, so he was paid under the table in cash.

Hesham made up for what he had missed out on during those lost high school years with a regimen of heavy partying. He failed to fulfill the conditions of his student visa and did not regularly attend school.

“I went clubbing every weekend,” Hesham said, grinning as he recounted his time in the Windy City. “I drank and danced and smoked. I met so many beautiful women.”

Hesham got a tribal tattoo on his bicep and another tattoo sometime later on his other bicep to cover up scars. He was becoming Americanized. But he was still very insecure and measured his importance and self-worth by the type of car he drove and the designer clothes he wore. He developed an addiction to weightlifting because he believed that the only way to get rid of the ugliness he felt internally was by improving his physical appearance.

Hesham was far from a model Muslim.

“When I came to this country, I denied my religion for a long time,” he said. “I didn’t go into a mosque to pray. I may have gotten down on my knees a couple of times and thanked God for the few things I had, but I wouldn’t do anything traditional.”

In 1999, Hesham’s friend, Bashar, called him from Saudi Arabia. Bashar was planning on moving to the United States and wanted to know where Hesham had been living.

“I’m in Chicago,” Hesham said. “It’s a great city!”

Big cities, however, frightened Bashar.

“He was scared. He started to talk about Portland,” Hesham said. “I remember saying ‘Portland?” I don’t know Portland. Where’s Portland?’ Bashar started telling me how it’s a smaller and quieter city and that it would be easier to make it in Portland. Also, it’s easier to find a woman, get married and get my papers and become a citizen.”

Bashar settled in Portland in the fall of 1999.

“He said he needed a roommate and what better roommate than the guy he got whipped with,” Hesham said, chuckling. “There were people Bashar was hanging around with in Portland we used to play soccer with in Saudi Arabia. So, I went to the library and looked up a book that says how to drive to Portland.”

Hesham loaded his belongings into his white Ford Mustang and drove west. He and Bashar got jobs pumping gas at an Arco service station.

Two months after settling in Portland, Hesham met a 20-year-old co-worker named Rosalee-Marie Andrews.

Hesham did not speak English very well but he managed to flirt with Rosalee. He asked her out to lunch.

“I told her all about me and my family and she told me her story,” Hesham said. “She was a simple person and I liked that. That’s what made me fall in love with her.”

One evening, Rosalee asked Hesham for a ride home. Instead, they ended up at Hesham’s apartment. Two months later, she found out she was pregnant. Hesham immediately proposed.

“I asked her if she thought if I also proposed to her family, and if I told them every single thing about me and my family, if she thought they would accept me,” Hesham said. “I kept thinking of what my father told me before I came here. He said that no one would accept me. But her whole family welcomed me. They did not judge me.”

The Phone Call

Hesham was at work at the Fast Trip gas station one afternoon in April 2000 when the phone rang.

“Hello,” a voice said when Hesham picked up the phone.

“Who’s this?” Hesham responded.

“It’s Hani.”

Hesham had not spoken with his brother for nearly a decade. By then, Hani had been on the radar of US intelligence for years. Hesham was oblivious to the news reports that started to appear in December 1999 linking his brother to Millennium terrorist plots in Jordan and to an Algerian named Ahmed Ressam, who was planning to blow up Los Angeles International Airport and was caught trying to smuggle bomb-making materials into the United States from Canada. Ressam told federal prosecutors and the FBI that Hani was a top al-Qaeda lieutenant, close confidant of Bin Laden and “facilitator” of terrorist attack operations.

Hani, was thought to be living in Pakistan at this time, and President Bill Clinton had reportedly asked government officials there to assist in capturing him. The FBI started to step up its surveillance of Hani, monitoring his cellular phone and other communications immediately following the failed plots in Jordan, according to two former FBI counterterrorism agents.

“Hani? Oh my God! I haven’t heard from you for a long time. How ya doin’, buddy?”

“I’m good, I’m good,” Hani said. “I heard you’re not doing good. What’s the matter, buddy?”

Hesham told Hani he was stressed out.

“I have a girlfriend and a baby on the way,” Hesham said. “I have money issues. I don’t have enough money to pay the bills. I missed some car payments.”

“Do you need some help?” Hani asked.

“I don’t need help,” Hesham responded. “I don’t want to ask the family for help. You know how dad is and how he will throw it in my face and say, ‘See? I knew you would fail and come crying to me for help.'”

“It’s OK,” Hani said. “It doesn’t make you less of a man if you ask for help.”

“I really don’t want to do that,” Hesham said.

“You know what, listen, I am going to talk to your sister, and they’re going to try and help you out,” Hani said. “Just take it.”

Hesham said Hani asked him how America was treating him and if he enjoyed living in the United States.

“I love this country,” Hesham told Hani.

During their approximately 15-minute conversation, Hani also asked Hesham about his plan to obtain citizenship.

“Hani said to me, ‘You know, as a Palestinian, you can get refugee status,'” Hesham said. “He stressed that point.”

Hesham said Hani’s voice sounded like he was “happy,” like “what I remember. A fun, good guy.”

“I kind of think he’s away from dad, he moved on with his life and he made his life,” Hesham said.

A few days later, Hesham said Hani called him at his apartment and told him that a sister was going to wire about $1,800 into his bank account. They spoke for another 15 minutes. Hani said he hoped he would have an opportunity to see Hesham. Then they said their goodbyes.

Hesham never spoke with Hani again.

Curiously, Hesham said he never asked Hani what he was up to. He never asked where he was living, where he was calling from, what his phone number was, whether he was married, had kids, or even how he got his phone number.

Hesham’s explanation is that he simply didn’t care.

“I assumed he got my phone number from my parents,” Hesham said. “They called me regularly and I told my mother how stressed out I was.”

Still, considering that Hani initiated the phone calls and that his every move at that time was supposedly being monitored by the CIA and FBI, did the National Security Agency (NSA), which at the time was headed by Gen. Michael Hayden, track it and pass the intelligence along to those agencies?

I filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request last year with the NSA to find out. On February 28, the NSA responded, issuing what is known as a Glomar response to the FOIA. (The term “Glomar response” came into use after the CIA, in the 1970s, denied a reporter’s request for information about the CIA-built ship the Glomar Explorer; the CIA refused to either confirm or deny the ship’s existence.)

Five special agents assigned to the FBI’s I-49 squad, which focused on Bin Laden and international terrorism out of the bureau’s New York Field Office, reacted with surprise when told that Hani called the United States in April 2000; the agents said they had no idea the calls had been made. Four officers assigned to the CIA’s Alec Station, which also focused on Bin Laden, said they, too, were unaware Hani made the calls.

Hani’s telephone calls, revealed here for the first time, which the FBI’s Portland field office learned about immediately after 9/11 when Hesham was arrested, was not shared with the so-called “independent” 9/11 Commission or the Congressional 9/11 panel.

Sen. Bob Graham (D-Florida), who co-chaired the joint Congressional inquiry into the 9/11 attacks, said it is “news to him” that Zubaidah not only has a brother who lives in the United States, but that Zubdaidah called the United States three times in April 2000 and spoke to his brother twice.

“The 9/11 Commission and our Congressional inquiry would have been very interested in this information,” Graham said. “We should have been told about it so we could evaluate the relative significance of the information, because it could have further contributed to our understanding of what happened before 9/11.”

The phone calls add yet another wrinkle to the official narrative of pre-9/11 intelligence and who knew what and when. The New York Times reported in June 2008 that Hani “was careful about security: he turned his phone on only briefly to collect messages, not long enough for his trackers to get a fix on his whereabouts.”

***

Hesham and Rosalee were married on July 14, 2000.

“Everything went downhill after that,” Hesham said, shaking his head.

The couple had moved into Rosalee’s parents’ house. They fought viciously. It was, a judge later wrote, “one of the most difficult relationships that’s every [sic] been presented to the Court ever.”

Bashar said he tried to warn Hesham about getting involved with Rosalee, who was previously living with Hesham in the apartment he had shared with his childhood friend.

“She was like a 10-year-old child in my eyes,” Bashar said. “She had a child’s mind. It was always ‘my way or the highway.’ I told him when he was going out with her to leave her alone. I swear to God I told him this because I knew she would be trouble in the future. But he fell in love with her.”

In August of 2000, Rosalee filed a Petition for Alien Relative with immigration on Hesham’s behalf, the first step toward Hesham obtaining a green card and becoming a US citizen. A month later, Rosalee gave birth to their daughter Nautica.

“I felt so good about myself,” Hesham said. “I had a daughter who was born a US citizen. For me, this was a very big deal. In Saudi Arabia, it meant nothing that I was born there. I was still a second-class citizen, an immigrant. I had no rights. But Nautica would get all of the benefits of being born in America. I was proving my father wrong.”

Rosalee and Hesham’s marriage, however, was falling apart. Rosalee stayed home to take care of Nautica, and in late 2000, after the couple moved out of her parents’ house, Rosalee began spending a lot of time with a 17-year-old drifter named Christina Marie Hodge.

Hesham clashed with Hodge, who was crashing at their apartment and babysitting Nautica, and his distrust of his wife’s friend formed the basis for numerous arguments. Hodge eventually left the United States and went to Germany in an attempt to stop using drugs, according to police and court records.

Hesham and Rosalee’s fights continued to escalate, over little things, such as their car. Rosalee wanted to use it, but Hesham needed it for work. She reacted by striking Hesham with a baby’s car seat. Hesham called the police and had Rosalee arrested at Domino’s Pizza, where she was working, in February of 2001, according to police records and court documents.

He didn’t press charges, but the incident angered her, and she vowed to make him pay.

Rosalee’s aunt, Patricia Naylor, would later say, “She kind of got vengeful after that.”

“I don’t think she got over it, and I think she set out to frame Hesham, and then after that, she would threaten him all the time she wanted, if he didn’t walk the walk, you know, do what she told him, that she was going to have him sent out of this country and cancel his immigration papers,” Naylor later said. “She did this constantly.”

Rosalee made good on her threats. She sent a letter to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) on May 31, 2001, stating that she wanted to withdraw her petition sponsoring Hesham for citizenship.

“Due to emotional and physical abuse I can’t stay in that marriage anymore and am going to file a divorce,” she wrote.

Rosalee did not tell Hesham that she filed a letter with INS to withdraw his application.

A day before Rosalee sent her letter to INS, White House Counterterrorism czar Richard Clarke told then-CIA Director George Tenet and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice that “a notorious al Qa’ida operative named Abu Zubaidah was working on attack plans,” according to Tenet’s memoir, “At the Center of the Storm.”

Arrested

In late July 2001, Hodge returned to the United States and reconnected with Rosalee. Hodge was broke, homeless and hanging out with drug addicts. Rosalee, who was working at Precision Castparts, took pity on her. She hired Hodge to work as a part-time babysitter for Nautica and said she could stay at her apartment. Once again, Hesham and Rosalee clashed over Hodge’s presence in their lives.

Hesham took issue with the fact that he had to pay Hodge for babysitting Nautica while she was living in their apartment, rent free, “eating our food and smoking our cigarettes.”

One evening, Hesham confronted Hodge and told her to pack her bags and leave. According to court documents, Rosalee interjected that Hodge couldn’t leave until they found a replacement babysitter. Hesham said no, went to grab Hodge’s bags and then grabbed her by the arm and led her to the door, where he tried to push her out of his house. But Rosalee insisted Hodge should stay, and Hesham took off.

That night, Hodge told Rosalee that a few days earlier, Hesham had made sexual advances toward her while she was cooking. She said he squeezed her buttocks. Rosalee encouraged Hodge to file a police report, which she did on August 9, 2001.

Hodge previously accused her uncle, who she was living with, of “sexually touching her” and “making sexual accusations to her,” Rosalee later testified.

Whether there was any truth to the claims against her uncle are unknown. Hodge’s aunt, when she learned about the accusations, kicked her out of their house, and Hodge never pressed charges.

Hodge told Portland police that Hesham threatened to rape her on August 6, 2001, and that he had forced her to have intercourse in January of that year, before she left for Europe, according to a copy of the police report, which she omitted from the story she told Rosalee.

Three days after Hodge filed the police report, Rosalee confronted Hesham about Hodge’s claims.

“I told her it was bullshit,” Hesham said. “I was so outraged. I told her Christina was lying and was trying to pit us against each other. I said I was working on my car all day in the driveway with Bashar when Christina said that happened.”

Bashar corroborated the story. But Rosalee was unsatisfied.

“I got up into his face and he was like, ‘I don’t want to talk about it anymore,’ Rosalee would later say. “And I said, I do. We need to talk about this, you know. And he was like, ‘I don’t want to talk about it no more. Get out of my face.’ And I said, you know, what are you going to do about it. What are you going to do about it”?

Hesham snapped. He slapped Rosalee across her face. She had a telephone in her hand and hit him on the elbow with it. He hit her back. She dropped to the ground and curled up into a ball. Hesham punched her on her back several times and then ran out of the house.

“I lost it,” Hesham said, sighing. “I just lost it. I will regret what I did until the day I die.”

Rosalee called a friend to pick her up, and the friend’s mother called the police. Hesham was arrested on assault charges.

A Visit From the FBI

About three weeks before the 9/11 attacks, on August 22, 2001, FBI special agents Christine E. Olson and Timothy Alan Lamb showed up at Rosalee’s apartment.

Rosalee used the meeting with the FBI to tell Olson and Lamb some wild stories about Hesham, according to a copy of the FBI’s interview report. She claimed that Hesham murdered someone at the behest of the Chicago mob, that he brought home crack cocaine and other drugs, and that he was going to return to Saudi Arabia with their daughter. She also provided agents with details about their violent altercation.

And then Rosalee talked about Hani.

“Per Hesham, his brother Hani Mohamed Abu-Zubaidah is a bomb terrorist,” the FBI report says. “Hani has no contact with his family and his family has no way to contact him unless he wants to talk to them…. For this reason, the father wants nothing more to do with Hani.”

The report, which appears to be based entirely on Rosalee’s statements to the agents, also made a strange reference to Ahmed Ressam.

Bashar, who recently became a US citizen, laughed off Rosalee’s claims about him attempting to get into FBI files and said it is “all lies.” He said his only contact with the FBI was when he was questioned about Hesham.

Rosalee never told Hesham that the FBI interviewed her. Hesham said he never told Rosalee that “Hani is a bomb terrorist,” as she alleged, and her assertion that his brother studied in Syria and Jordan was incorrect.

Rosalee later said she lied to the FBI during her interview, which is a felony. She also admitted that she lied to INS when she was interviewed separately by the agency that month.

“The reason why [was] because I was very mad at him,” Rosalee would later say about why she lied to the FBI. “I wanted so much revenge on him. It hurts me to say it; I wanted to hurt him badly, very bad. I wanted to screw him in any way I could.”

Rosalee later admitted that she also fabricated a story about Hani, that Hesham never told her he was a “bomb terrorist,” but that he told her Hani was “good on computers.

Rosalee said she contacted Olson, the FBI agent, in October 2001 and told her the allegations she leveled against Hesham “weren’t really true.” Olson, according to Rosalee, said, “I could kind of tell that.”

FBI agents Olson and Lamb never spoke with Hesham after interviewing Rosalee. According to a US official, the Portland field office was “preparing the necessary paperwork to interview Hesham,” which, according to another US counterterrorism official, would have included an opportunity for the CIA “to contribute to this interview.”

“9/11 happened before this went forward,” the US official said.

The FBI never charged Rosalee with false statements. But it was already too late for Hesham.

The 9/11 Attacks

Hesham was working at Franz Bakery at the time of the attacks.

“I was in the break room,” Hesham said. “The television was on and everyone was screaming, ‘Look at the planes hitting the towers!’ I was shocked. You know, even though I wasn’t a US citizen, I felt like one because I lived here. So, that day, it just really affected me. I felt like my country was attacked.”

Hesham said there was a knock on his door a week later.

“They were very nice,” Hesham said. “It was a man and a woman. They asked if they could speak to me and ask me a couple of questions. I said yes and welcomed them inside my apartment.”

The agents showed Hesham photographs of his brother, Hani, but he said he did not recognize any of them. The photographs were of a four-year-old passport photo and computer generated images of his face with a beard, a goatee, blue hair and green hair, clean-shaven, with and without eyeglasses.[2]

“I looked at the pictures for a couple of minutes,” Hesham said. “The agents said, ‘We’re going to educate you. Look at his eyes.’ I told the agents I didn’t know who that guy was, and I don’t agree with any of the stuff they said he did. They said thank you very much and they left.”

A day later, Hesham was arrested.

Hesham was charged with violating the conditions of his student visa. According to his immigration case file, on September 14, 2001, INS issued a letter to him stating that because Rosalee withdrew her relative petition in May 2001, he was in the country illegally.

Hesham was placed into removal proceedings and held in solitary confinement. Hesham said, “I was allowed in the rec yard for one hour. There was a little window at the top of the wall in my cell but I couldn’t see out of it.”

Hesham maintained that the FBI and INS wanted to deport him because he was the brother of an alleged al-Qaeda operative. He said about ten different FBI agents interrogated him about his brother “a few times a week” while he was in custody.

“The FBI thinks just because that guy’s my brother I should know everything they say he was doing? Why?” Hesham said. “To this day, I don’t know what my mother and father knew. I don’t know what my brothers and sisters knew. Every time I bring up Hani, I get cut off and they change the subject.”

I filed a FOIA request with US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), formerly INS, for Hesham’s entire immigration case file last August. In late January, the agency turned over nearly 1,000 pages, an unusually large file, but withheld 116 pages in full, 91 pages in part, and referred 44 pages “in their entirety to two government agencies for their direct response to you.” One of those agencies is clearly the FBI. The identity of the second agency is unknown.

During appearances before Immigration Judge Michael Bennett in October 2001, the issue of whether Hesham could be released on bond came up, but the government claimed he was a “security” risk, according to court documents.

Court files also show that the proceedings were held in secret and a court-appointed officer blocked entry to the courtroom.

Hesham did not have an attorney during his first few court appearances, where he opted for an Arabic interpreter to speak on his behalf. Bashar raised about $1,500 from friends for an attorney and gave the money to Rosalee, who attended the immigration hearings with her family and started the process of the relative petition with immigration on behalf of Hesham. Bashar asked Hesham’s father for money to pay his son’s legal costs. Mohamed said no.

“It was his choice to go to America and make it on his own without my help,” his father told Bashar. “So, let him make it.”

Hesham said his first attorney dropped out of representing him because of the complicated nature of his case.

On October 19, 2001, Michael Rolince, the section chief of the FBI’s International Terrorism Operations Section, sent an “action memorandum” to Ronald J. Smith, the district director of INS. The memo cited Olson and Lamb’s FBI report, which was written on October 12, 2001, that contained Rosalee’s statements about Hesham to the FBI, which she admits were false.

Six days after that memo was distributed, the district attorney for Multnomah County in Oregon charged Hesham with felony assault for hitting his wife and attempted rape and sexual abuse related to the allegations Hodge leveled against him, in which she said he touched her buttocks and threatened to rape her. It is unknown whether Rolince or any other federal law enforcement official provided similar information to state authorities.

On November 6, 2001, Oregon Assistant US Attorney Charles Gorder, an antiterrorism prosecutor, sent a letter to Wesley Scott Cihlar, the assistant district director of detention and removal for INS, and asked him to arrange to have Hesham released to the custody of Multnomah County authorities for “prosecution on state criminal charges.”

Judge Bennett ordered Hesham released.

“I thought I was getting out,” Hesham said. “But as soon as he let me go, I was then arrested by the police and brought back to state jail.”

On November 23, 2001, Hesham was indicted by a grand jury. The FBI returned to his cell a few days later.

“They were coming a lot,” he said. “A few times a week. They took me to a room and would question me for hours. Same questions over and over again. Where is your brother? Do you know where Bin Laden is?”

On one occasion they spent 90 minutes interrogating him about Hani and the rest of his family and recorded the interview. Hesham did not have an attorney present during the interview sessions with FBI agents. He said that during one of the interviews, he disclosed that he spoke to his brother in April of 2000 and that Hani spoke to a sister and she arranged to have some money wired into his bank account.

“They flipped out,” Hesham said. “They said they thought I was part of a sleeper cell. They asked me if I had ever been to a training camp, if I know al-Qaeda, Bin Laden, the jihadists,” Hesham said. “Then they continued to show me pictures of my brother. They said, ‘It’s him. That’s your brother. Pay attention to his eyes. Look at his eyes.'”

Hani was involved in the planning of 9/11, the agents told Hesham, and was a high-ranking member of al-Qaeda. The FBI agents wanted Hesham to provide details about where Hani went to school and where he was living.

“Then they wanted me to tell them everything about my brothers and sisters, where they went to college, what they studied, who my mother and father were,” Hesham said. “I answered all their questions. I told them I am a good person. I love America. Why are you doing this to me?”

Hesham missed his daughter. He vowed that, if released, he and Rosalee, who was about seven months pregnant, would go to couples counseling. He was desperate.

“I was offered a deal,” he said. “I just wanted to get out. I didn’t want to be in jail anymore. I did hit my wife, and I felt I should be punished for it.”

The rape charge was dropped, and the felony assault and sexual abuse and harassment charges were reduced to Class A misdemeanors for domestic violence and harassment.

“Just plead no contest, pay a fine and you’ll be on probation for three years,” the public defender told Hesham. “Immigration won’t have anything on you. The charges are misdemeanors, not felonies, so you won’t be deportable. You can be back with your family tomorrow.”

“OK,” Hesham said. “I’ll take it.”

But Hesham said he did not understand that by pleading no contest, he would essentially be accepting the charges against him.

“I did not understand the law and my public defender did not explain this to me,” Hesham said. “I did not know that no contest was like pleading guilty.”

The plea agreement he signed, however, clearly states that if he is not a citizen of the United States, “my plea may result in my deportation from the USA, or denial of naturalization.” [Emphasis in original.]

Hesham signed the papers without a close read.

Unfit to Remain in the US

When Hesham walked out of the courthouse on January 8, 2002, INS agents were waiting. They took him into custody and detained him in immigration jail. His case was back before Judge Bennett.

INS charged him with being removable on two grounds of deportability, domestic violence and sexual abuse of a minor (related to the alleged touching of Hodge’s buttocks), which, under immigration law, can be defined as an aggravated felony. The judge determined that the harassment charge he pled no contest to fell within the definition of a crime of “moral turpitude,” a deportable offense, said one of Hesham’s former attorneys, Tilman Hasche of the Portland-based law firm Parker, Bush & Lane.

Hesham’s lawyers vigorously challenged the factual evidence and legal arguments pertaining to the INS prosecutor’s assertion that misdemeanor harassment of Hodge could be defined as a sex crime, which would make Hesham inadmissible to the United States. But Bennett found in favor of the prosecution.

“I just wanted to die,” Hesham said. “That time, I don’t have too much faith. I lost a lot of faith. I kept saying, Why, God? Why are they doing this to me?”

Hesham begged Judge Bennett to release him from prison so he could be present at the birth of his second daughter, Nastasja. Bennett declined.

“I was in jail when my daughter was born,” he said. “I have to live with that for the rest of my life.”

Hesham tried to make the best of his detention. He volunteered to be an Arabic interpreter. The FBI interrogations, however, increased.

“They even started to bring someone who spoke Arabic,” Hesham said. “I kept telling them, whatever I know about my brother being involved in terrorism comes from what you guys told me. But what I know about him is the exact opposite.”

An adjustment of status hearing was held to consider Hesham’s appeal on March 27, 2002.

Rosalee testified at Hesham’s deportation hearing that their fights “began with me.”

“I have a lot of problems,” she said in court. “I’m very emotional. I’m very sad, very depressed, not a very happy person. I’m not happy with myself. Basically, what Hesham has done to my life was try to help me better myself, and I thought that was him attacking me, so I kept him back many times.”

“When I would get angry or mad about something that was so little, he would like, you know, don’t worry about it,” said Rosalee. “You know it’s okay. And I’d just go off on him.”

Rosalee’s mother, Rosalind Lynn Andrews, and her aunt both testified on Hesham’s behalf and said that Rosalee “seemed to get a direction in life” after she met Hesham.

“They both have anger problem issues,” Rosalee’s mother testified at Hesham’s removal proceedings. But “deep down they both care a great deal about one another” and “they’re crazy in love with each other.”

Andrews also said her daughter had a history of “acting out,” “fabricating” stories and received medical treatment for psychosis when she was younger, but as she got older, her behavior became progressively worse.

Rosalee had a history of emotional instability that included violent outbursts. As a child, she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and as afflicted with attention deficit disorder. When she was in her late teens, she threatened to burn her aunt’s house down and “break her windows and lay on the street and get hit by a car” because her aunt would not give in to Rosalee’s demands.

Bennett acknowledged that Rosalee has “terrible problems” that “predate her relationship with” Hesham, yet Bennet said it was Hesham who lacked credibility, even though Rosalee admitted she lied to the FBI and INS. Bennett also accepted claims made by Hodge, whom he described as a “street urchin,” about Hesham touching her buttocks in a sexual nature, because Hesham pled no contest to the charges.

On March 28, 2002, Judge Bennett ordered Hesham deported to Saudi Arabia, a country in which he is not a citizen. Judge Bennett’s decision was made on the same day CIA and Pakistani intelligence captured Hesham’s brother, Hani.

“With regard to credibility,” Bennett wrote, “the Court finds respondent’s wife is credible and in fact most all of this information about terrorist bombers and connections to nefarious organizations in the Middle East or other kinds of information she said she was saying to get back at him. And they have nothing to do with my determination … This case is not about that.”

Prior to Bennett’s decision, Hesham testified numerous times that he was remorseful over what transpired between him and Rosalee and begged for a second chance so that he could be reunited with his family. Judge Bennett said Hesham was “protesting too much.”

Hesham’s co-workers and friends and Rosalee’s family sent letters of support to the immigration court attesting to his character.

Hesham is “helpful, polite, kind and considerate and is a good example,” says a letter signed by his mother-in-law, Rosalee’s aunt, his boss and a friend.

But it did not sway Bennett.

Hesham was devastated. His father was right, he thought.

“I’m a failure,” he said. “I’m shit.”

Hasche believes Hesham received a fair hearing and that “Judge Bennett followed the law, as he understood it.” But Hesham believes the judge’s final determination was based on the FBI’s interference.

Entries in the client activity report contained in Hesham’s legal files that were provided to Truthout show that the lead attorney with Parker, Bush & Lane who handled Hesham’s case, Steven L. Kay, had “teleconferences” with FBI special agent Olson, which several immigration attorneys said is unusual.

Kay said he’s now a political activist and a theater actor and doesn’t remember anything about it. He later changed his story.

“I spoke to the FBI about him and his brother, yes” Kay said. “The agent made it clear to me they were using him as leverage in their quest for his brother. They would do anything to find his brother, the agent said to me.”

Kay surrendered his law license in 2005 while disciplinary proceedings were pending against him related to other clients he represented.

Hasche, who took over Hesham’s case from Kay when Kay and the firm parted ways, said he was unaware Kay had spoken with the FBI and, additionally, did not know Hesham was being held in solitary confinement or that the FBI paid regular visits to Hesham while he was in custody of immigration. If he had known that was “allegedly” happening, he said, he would have referred Hesham to the Oregon Federal Public Defender’s office.

Elaine Komis, a spokesperson for the Executive Office for Immigration Review, declined to make Judge Bennett available for an interview. She said a FOIA request would need to be filed for information about conversations Bennett had with the FBI regarding Hesham.

After his brother was captured, the FBI showed up again to speak with Hesham.

“They were really, really mad,” Hesham said. “They said, ‘You lied to us. We showed you the pictures and you said it’s not your brother. You’re hiding something.’ I was like ‘I’m not hiding anything. I’m here. You guys could do whatever you need to do to make sure I am a good guy. I have not hid anything. It’s just that I have not seen my brother in almost 15 years and the pictures you have doesn’t look like my brother. The beard, everything, the guy looks totally different than what my memory is.”

Pictures released many years later of Hani taken on the night he was captured looked nothing like the passport photograph the FBI and CIA showed Hesham.

Hesham said the agents then told him, “Well, we got your brother; we caught him, and the person in the pictures is him. So, stop saying you don’t know who it is.”

Hani looked so different after he was captured that not even the CIA was certain it was him. To be sure they apprehended the right person, the FBI asked Hesham if they could conduct a DNA test on him, which he agreed to.

“They swabbed my mouth,” Hesham said. “Then they said they may need me in the future.”

A couple of weeks later, George W. Bush gave a speech to a Republican luncheon in Greenwich, Connecticut, where he announced that the United States had captured Hesham’s brother.

“The other day, we hauled in a guy named Abu Zubaidah,” Bush said. “He’s one of the top operatives plotting and planning death and destruction on the United States. He’s not plotting and planning anymore. He’s where he belongs.”

Hesham remembers that moment well. A prison guard walked over to his cell and said he had watched a news report about Abu Zubaidah’s capture.

“Is that you? Is that why you have been here for such a long time? You’re the terrorist,” the guard said.

Hesham would remain in INS custody for the next 13 months while his attorneys appealed his deportation to the Board of Immigration Appeals, which held up Judge Bennett’s decision, and to the Ninth Circuit. Rosalee relied on food stamps to take care of their daughters.

In January 2003, Hesham gave up the fight, asked for the appeal to be withdrawn and said he would not challenge the deportation.

“Deport me,” he wrote on a note to the judge. “I want to be deported ASAP.”

INS then tried to deport Hesham to Yemen, Morocco and Egypt, but those countries declined to take him. He was a man without a country. Just like he was in Saudi Arabia.

On April 11, 2003, after nearly two years in immigration prison, Hesham was released from custody by INS under an order of supervision and placed on probation. He also had to attend domestic violence counseling.

Hesham was still subject to removal if the United States could find a country that would take him, and INS continued to try and find one after his release.

Hesham had never embraced his second daughter, who was now a year old. His firstborn was two and a half.

“I was heartbroken,” he said. “I could see how difficult this was for my children to suddenly have me back in their lives. I was a stranger to them.”

Hesham and Rosalee divorced in February 2006.

Recruited

Hesham developed a deep hatred for his brother, Hani. He blamed Hani for destroying his life.

“Let’s face it, if my last name was not Abu Zubaidah, I wouldn’t be in this position,” Hesham said. “The FBI wouldn’t be coming to see me all the time. I would probably be a US citizen by now. It’s all because of that guy that my life is fucked up. If he did what the FBI tells me he did, then he should pay. If he is the mastermind terrorist they say, he should be brought to justice. But don’t penalize me for his crimes. I’m a good guy. Screw him, and if my life is fucked up because of him, then fuck him!”

Less than a month after he was released, Hesham met another woman.

Twenty-five year-old Jody Hammond would stop into the Fourth Avenue Smoke Shop in downtown Portland every morning on her way to the restaurant where she worked as general manager.

There was a new guy behind the cash register, and he struck up a conversation with her.

“It was just small talk,” Jody said. “But he always managed to put a smile on my face.”

Hesham asked her out. A month into their relationship, he told her everything he had gone through over the past three years with immigration, and how his brother, Hani, was a notorious terrorist.

“It was like a three-hour conversation,” said Jody, who at the time had just ended a six-month marriage. “I think he was expecting that I would run away. But you don’t leave someone because of an issue they have with the law. In my heart, I believe Hesham is a kind, gentle person. When I first met him we clicked on a really deep level. He has a great sense of humor. He’s smart and knowledgeable about so many things. He’s very spontaneous, wild and crazy in a good way. He’s my complete opposite. We match perfectly in my head.”

One might expect that a Muslim of Palestinian decent would clash with an American Jew, but Jody and Hesham hit it off as they both denounced their religions. Where Rosalee was in-your-face and vindictive, Jody was soft-spoken and supportive.

She became Hesham’s biggest advocate. She spent all of her free time researching immigration law and writing letters to members of Congress and state lawmakers in hopes of getting Hesham’s record expunged. Jody sent a letter to US Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Oregon). She got a response saying, it wasn’t their issue.

Jody and Hesham consulted with immigration lawyers to take another look at his case. But when they looked over his file and found out who his brother was, the attorneys said, “No judge would ever touch this.”

Hesham’s hatred of Hani would usually peak toward the end of every month, when he was preparing to check in with his probation officer. A few days before he went in, he would slip into a depression, vomit and become paranoid about being returned to INS custody.

“I was a wreck,” Hesham said. “I would have dreams that I was back in jail, back in solitary and nobody knew I was there. I kept thinking of Hani and how I wished he would drop dead for what he caused to happen to me.”

While Jody was campaigning to clear his name, Hesham was trying to figure out his own ways of proving to the US government that he was worthy of being a citizen of the United States.

He tried to enlist in the military.

“I would have fought for this country,” Hesham said. “I would have gone to war for America. This is how much I love this country.”

Hesham visited the Army and Marine Corps recruiting offices. The recruiters plucked him out of the line. Hesham’s muscular frame and the fact that he spoke Arabic made him an attractive recruit.

“When I sat down with the recruiters they immediately wanted to sign me up,” Hesham said. “When I told my story to them and talked about Hani, they got a sad look on their face because I think they really wanted me. They said they doubted they would be able to take me but they would try. They called back a few days later and said sorry, but that I should keep trying in the future.”

In February 2006, Jody gave birth to a daughter, Emily Cecl Abu Zubaidah Hammond.

“We didn’t want Abu Zubaidah to be her last name because we didn’t want the name to hurt her,” she said.

Hesham was seeing his other daughters less frequently. He said Rosalee often left with his children whenever he was scheduled to see them.

(Photo: Lance Page / Truthout)Hesham seemed to be doing well, considering he could be deported at any time. He launched a wholesale car dealership with two friends and started earning good money. He purchased designer clothes and expensive jewelry and showered Emily and Jody with gifts.

(Photo: Lance Page / Truthout)Hesham seemed to be doing well, considering he could be deported at any time. He launched a wholesale car dealership with two friends and started earning good money. He purchased designer clothes and expensive jewelry and showered Emily and Jody with gifts.

But he couldn’t stop thinking about the green card. It drove him crazy.

One day in mid-2006, he paid a visit his business partner, Bilal Alsbou, who had a day job working as a salesman at a new car dealership. Alsbou was used to seeing Hesham distraught over his immigration status. He’d offer mild support and say things like, “Hang in there.”

“I walked to his desk and saw a lady sitting with him in his office,” Hesham said. “I thought it was a customer. I asked him what cars were available this week. I was trying to make him look good in front of the lady I thought was a customer.”

Hesham walked out and then Bilal came out about five minutes later with a list of cars that were available for sale. He told Hesham to “stop showing off” because the woman in his office was someone he worked closely with and she wanted to know who the “hotshot” that came in was.

Hesham went to see his other business partner.

“You need to stop being so flashy,” his business partner said. “You don’t know who you’re talking to.”

Hesham was confused and shrugged it off. The next day he and Jody went to see Alsbou.

“That woman you saw in my office yesterday, she’s really interested in working with you,” Alsbou said. “Her name is Diane and she works for the FBI.”

Jody blurted out, “No.”

“I see what you’re going through,” Alsbou said. “These people can help you. Think about it.”

“No,” Jody said again.

Hesham and Alsbou spoke to each other in Arabic. Then they shook hands.

On their drive home, Hesham told Jody, “This could be my chance at being a US citizen. Please, let me try.”

Hesham was desperate.

“I was seeking help from anywhere,” he said. “Who better to help me than the FBI? They are the people that helped put me in this position I am in.”

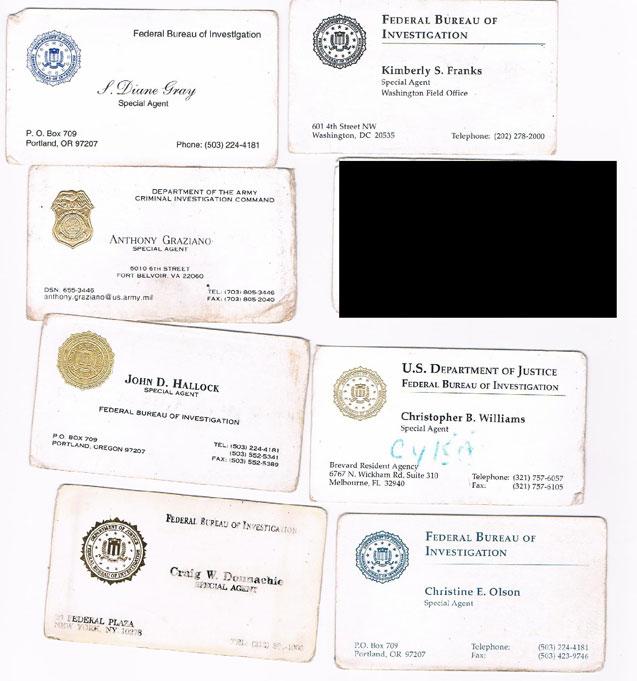

L. Diane Gray was a special agent with the Portland FBI field office, according to a copy of her business card, which Hesham gave me.

Hesham met her at a Portland Starbucks.

“Of course, the first thing that comes out of her mouth is talking about my brother,” Hesham said. “Just rewind the whole thing. Then it went a bit hostile: Tell me when you talked to your brother. What was he like as a kid? Where is the money? Why did I get money from him right after he called? What I know about my brother, where he lives. She asked me about my family, where he stands with the family.”

Hesham said Gray was “very serious” during their hour-long meeting and he felt like he was being “profiled.”

He and Gray met about six or seven more times over the next months. At one point, Jody followed Hesham. She said Gray spotted her when she entered the Starbucks and the FBI agent put her hand over her face. Hesham said Gray told him, “I can’t let her see me.” He then waved Jody away.

After their last meeting, Gray told Hesham that if he could help the bureau, maybe she could help him obtain a green card.

“I can’t make any promises, but I will try,” Gray told Hesham “For now, help us out.”

Hesham said he would do “whatever it takes” to “prove to you that I am a good person and fix my situation.”

Gray called him two weeks later and they met again. She brought an envelope with about ten photographs. A majority were Somalis. But there were also photographs of Iraqis and Saudis, Hesham said. [3]

“Do you recognize any of these people?” Gray asked Hesham.

“Nope,” he said.

“I’d like you to go to the mosque and find out what these people are up to,” Gray said. “Find out if any of those people are helping terrorists.”

“I will keep my eyes open,” Hehsam said.

“Do you have any idea or know any people who would try to plan something or know of anyone who acts suspicious?” Gray asked.

“No,” Hesham said.

Hesham said he and Gray drank their coffees and talked about family for about 15 minutes.

“She was really nice,” Hesham said.

Gray contacted him again a month later. This time she wanted to meet at a different coffee shop in downtown Portland.

Gray asked Hesham if he attended any mosques. He wasn’t religious, but told her he tried to attend Friday prayers at Masjed As-Saber, the Islamic Center of Portland. Gray told Hesham that the mosque was under surveillance.

“I want you to start going to the mosque every Friday,” Gray told Hesham. “And I want you to try to get some information to me. I need to know more about the imam and about the finances of the mosque. Is he helping to fund jihad? Is he helping terrorists? I need to find out who is in charge of the finances and where the money is coming from. Anything going on there that’s abnormal, tell me.”

“No problem,” Hesham said. “I’ll try.”

Gray then handed an envelope to Hesham that contained about three or four hundred dollars.

“When I first saw the envelope, my heart started to beat really fast,” he said. “I thought it was my papers.”

Hesham took the money but told Gray that he needed a promise from her that she would help him with his immigration status.

“You have my word,” she said.

Hesham said the only time he signed any papers for Gray is when he accepted the cash she gave him.

The FBI has been trying to link Masjed As-Saber, and the imam of the mosque, Sheik Mohamed Abdirahman Kariye, a native of Somalia, to al-Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden for at least a decade.

In September 2002, Portland FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) at Portland International Airport arrested Kariye as he was preparing to board a plane for Dubai. Kariye was charged with two felony counts of unlawful use of a Social Security number. Assistant US Attorney Charles Gorder said that residue from TNT was found in the imam’s luggage. Moreover, the government alleged that the mosque funneled money to a charity set up by Bin Laden’s former personal secretary, Wadih El Hage.

The government also claimed that Kariye financed a group of American Muslims known as the Portland Seven to fight in Afghanistan against American soldiers. One of the defendants prosecuted in the case is said to have told a confidential witness that Masjed As-Saber was “the only mosque to teach about jihad.”

Kariye was never charged in the case.

Hesham said Gray told him to report back to her what the money collected from those worshipping at the mosque was going to be used for. He told her that the imam and others at the mosque said the money they collected following prayer services would be used for humanitarian purposes.

“She was concerned the money is going somewhere to support terrorism,” Hesham said. “She wanted to know who was in charge of the money and where it was taken after it was collected. I didn’t ask any questions. I just did what I was asked.”

Gray also asked Hesham to attend Portland’s Shia mosque, the Islamic Center of Portland, and spy there, too. Hesham recalls that on one occasion, Gray wanted him to attend a service given by a guest speaker, whom Hesham said he was told the bureau was monitoring, and find out what the speech was about and whether the guest speaker, whose name he does not remember, was encouraging any of the congregants to become jihadists.

Hesham did not wear a wire or use a tape recorder when he was spying.

In the nearly three years Hesham worked as a confidential informant for the FBI, he was shown hundreds of pictures of individuals Gray told him the FBI was suspicious of. He said he never heard the imams or any of the congregants at the mosques discuss “jihad,” or terrorist attack plans.

“They seemed like good, normal, hard-working, family people,” he said. “I told that to Diane.”

Gray and Hesham became close. He considered her a friend. At one point while he was working for her, she stepped in to help expedite his work permit. In 2009, she was getting ready to retire from the bureau and she had some news to share with Hesham. It was about his immigration case.

“I want you to know that I did everything I could,” she told him. “But your case is sitting on a shelf somewhere and no one can touch it. It’s just too complicated. I can’t do anything to help you. Good luck to you and I hope things get better for you.”

Hesham was hurt. He felt used. He thought of himself as a rat.

“They could have helped me,” Hesham said. “They just didn’t want to.”

Jody had predicted it.

“I told him not to work with the FBI because they were just going to use him,” she said.

Before Gray retired, she told Hesham that the bureau thought he did a great job and she wanted to introduce him to other FBI special agents from the Portland field office who wanted him to work on another assignment.

Business cards Hesham collected over the years.

Business cards Hesham collected over the years.

One of the agents who Diane said was going to be taking over for her was Christine Olson, who had, unbeknownst to him, interviewed Hesham’s ex-wife Rosalee and had held “teleconferences” with his former immigration attorney. Now here she was, trying to recruit him for another spy job.

Hesham was unaware Olson played a role in his immigration case until I revealed it to him. He never had a copy of his immigration file, where her name appears several times, or a the interview report Olaon and Lamb wrote that was buried in his attorneys’ files.

Hesham met with Olson twice. The first meeting was just to get to know him and to butter him up.

“Christine told me that everyone was happy with the work I did,” Hesham said. “I told her, That’s great, but you guys didn’t help me, and I showed them good faith for close to three years.”

The next time Hesham met with Olson, she brought along another agent, John D. Hallock, and explained the new assignment to him. They wanted him to infiltrate “jihadist web sites” and pose as “an extremist to enlist people in terrorism and attacks against America so they could catch them.”

“They needed somebody who spoke Arabic to get in there,” Hesham said.

This time Jody put her foot down.

“Hesham doesn’t use a computer,” she said. “So really, the person who would have been doing this kind of work would have been me showing him how to get onto these web sites. I said, ‘No way.’ And aside from that, after the way they treated him, why should we keep helping them?”

Besides, Hesham and Jody were getting ready to move out of Portland.

“I said, ‘Thank you, but I am moving to Florida and I can’t do this work anymore,'” Hesham said. “I could see she was upset. But I was done with the FBI.” [4]

But the FBI wasn’t done with Hesham. Gray set up a meeting between Hesham and an FBI special agent named Craig Donnachie, who worked out of the bureau’s New York field office.

Donnachie was assigned to the bureau’s JTTF. He was the case agent responsible for Hani and knew a great deal about him, according to the book “The Black Banners,” written by former FBI special agent Ali Soufan, who first interrogated Zubaidah at a black site prison in Thailand. Donnachie was supposed to accompany Soufan to Thailand in April 2002, but the bureau was unable to reach him because it was Easter.

If Donnachie was responsible for monitoring Hani, did he know about the calls he made to Hesham in April 2000? Donnachie never returned my calls.

Anthony Graziano, a special agent with the Army Criminal Investigation Command, showed up one day with an FBI agent from Washington, DC and accompanied Donnachie to the meeting.

Donnachie asked Hesham to go over the phone calls Hani made in April 2000.

“What did he tell you? Did he mention anything to you?”

Donnachie then pulled out pictures of Hani, the same six or seven passport photographs Hesham was shown after 9/11.

Hesham was annoyed. He had told the story so many times before. So he asked the same question he’s been asking the FBI for years.

“Can you guys help me?”

Donnachie said he couldn’t because “it would look like we’re buying you off.”

Donnachie told Hesham that Hani was involved in “jihadism” and was “very close with Bin Laden.”

“Why didn’t you guys come to me a long time ago? Before 9/11?” Hesham asked. “Maybe I could have helped you then. Did you ever think about that?”

Neither Donnachie nor Graziano responded.

Kathleen Wright, an FBI spokeswoman, declined to answer questions for this story, except for one, about Hesham’s work as a confidential informant.

“We do not confirm who may or may not have provided information to the FBI,” Wright said.

The Ankle Bracelet and More Unannounced Visits

Hesham was placed in Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) controversial Intensive Supervision Appearance Program (ISAP) when he settled in Florida in April 2009. He had to wear a bulky ankle bracelet, keep a log of his every move and hand that in to ICE agents. He had to make daily phone calls to an automated service and check in. If he missed one, he would be thrown in jail. He was a prisoner again.

“Can you believe this is what they did to me after I worked with the FBI for three years?” Hesham says. “As a Palestinian growing up in Saudi Arabia, I had no rights. This feels just like that. I was like a dog, a slave. I really felt like I was being tortured. They tortured my mind.”

Jody reached out to Elizabeth Godfrey, an ICE removal officer who processed Hesham’s release from immigration prison, for help. Hesham built up a good relationship with Godfrey, who, he said, told him before he left prison that Judge Bennett was dead-set on deporting him as soon as he stepped foot into the courtroom.

Godfrey told Jody to write a letter to ICE.

“She told me what to say. She was so sweet. I sent her flowers,” Jody said.

Jody decided to hand-deliver the letter. It argued that Hesham should be removed from the ISAP program. She says when she tried to submit it to one of the ICE agents, he threw it in her face, literally, and said Hesham wasn’t getting off the program.

She reached out to Florida’s Republican Congressman Bill Posey. She wrote a letter that explained the incident that took place at the immigration office and went through Hesham’s history and the notoriety of his case.

The Republican lawmaker responded by letter on June 23, 2009.

***

Hesham got a job driving a truck for a family-owned produce business in Melbourne. He lived in a tiny, two-bedroom house in conservative Palm Bay, about ten miles away. He tried again to enlist in the military but was rejected. US Marine Corps stickers he grabbed on his way out of the recruitment office are plastered on the bumper of his used Mercedes Benz.

Months went by and some familiar faces started to appear on Hesham and Jody’s doorstep.

It was Graziano. He warned Hesham he would be back.

“He wanted to talk about Hani,” Hesham said. “That’s why he showed up. It’s all about my brother. Always about my brother.”

Graziano told Hesham he met Hani at Guantanamo.

“Your brother seems personable like you,” Graziano said. “But he told me if he ever got out, he would kill me. He’s a soldier and I’m a soldier. What do you think about that?”

“I have nothing to do with my brother,” Hesham said. “I don’t believe in any of the things you guys say he stands for.”

“Good,” Graziano said. “You have a good attitude.”

“How did my brother become like this?” Hesham asked Graziano.

“He was brainwashed,” Graziano said. “All the jihadists are brainwashed. They believe they will go to heaven and get 72 virgins.”

“Who wants virgins?” Hesham quipped. “I wouldn’t want a virgin.”

Graziano laughed. He told Hesham the government might need him to testify before a grand jury down the road in Virginia. Maybe down the road.

“Testify? About what?” he asked. “I have no information for you guys.”

“Your brother,” Graziano said. “At his trial.”

“I don’t know anything,” Hesham said. “Why do you need me to testify? I don’t feel comfortable doing that. Can’t you guys just let me live a normal life?”

“You said you want to help America. Do you have something to hide?” Graziano asked.

“No,” Hesham said. “Look at me; look at where I am. Look at my life. Do you think I have been hiding anything?”

“It will be easy,” Graziano said. “You’ll be shown pictures, and you’re going to say, ‘Yes, that’s my brother.'”

Graziano did not return calls for comment. A spokesman for the Army’s Criminal Investigative Division declined comment.

Jody was pissed that so much attention was being paid to Hani while Hesham was “right here” and suffering too, and no one even knew it. She did Google searches about Hani and posted comments under Hesham’s name on stories highlighting his plight in hopes a journalist would spot it and contact them.

Jody learned that Hani was tortured. She broke the news to Hesham. He was conflicted. He thought maybe Hani was being used, too.

“Whatever he had done, he should be judged fairly,” he said. “It’s very sad what was done to him. I don’t know what he has done to deserve this happening to him. I feel really badly for him. He’s still my brother and I love him. It’s very hard. In one way, if he hurt a lot of people, he deserves to be punished. But not like that. I feel sad and merciful. It’s confusing.”

Hesham called me back a few hours later. He’d been thinking about Hani.

“I’ll tell you something,” Hesham continued. “I don’t agree with any jihadists. I think anyone who wants to come to this country and kill people is not a good person. But I don’t believe my brother is that person. I don’t believe any of the things the government says he did. I just don’t believe it. Maybe I am in denial.”

“You don’t believe your brother was a terrorist?” I asked Hesham.

“No, I don’t,” Hesham said. “Still, to this moment, I don’t believe it. All I know is what the FBI told me about him. This guy used to be a great, fun guy, he’d play his piano.” Hesham trailed off as his emotions welled up. “He was a good guy. And if I say good guy, I mean good person, good citizen, a good man. I believe he’s a good person.”

The Subpoena

Graziano paid two additional visits to Hesham. One of the visits was to introduce Hesham to a local FBI field agent, Christopher B. Williams, who Jody said was “really jumpy” around Hesham, and to Kimberly S. Franks, a special agent with the Washington, DC field office. They all went out to dinner and got drunk, Jody too.

“Everyone was talking to him about going out to Washington to testify against Hani and the great thing he would be doing for the country,” Jody said. “Hesham really did not want to do it. They were acting like they were his best friends. It was sickening. I got up and left. I couldn’t handle it.”

In October 2010, Graziano and Franks returned to Florida, and they brought along another FBI special agent. Hesham doesn’t remember the agent’s name. He thinks it may have been Donnachie, but he’s not sure.

Hesham met Graziano and the agents at a bar. The agents handed Hesham a subpoena. He was scheduled to testify before a grand jury at the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia sometime in October 2010. He asked if he needed an attorney.

Graziano told Hesham that since he is not being charged with anything, “There’s no need for a lawyer.”

About a month or so later – in mid-October 2010 – he got a phone call telling him to be ready in two days. The government got him a business-class ticket. Jody dropped him off at the airport. She was going to meet up with him a day later. Although he wasn’t looking forward to testifying, Hesham was excited he could fly without incident. It was the first time he was on an airplane since he arrived in the United States. He had a window seat and stared at the landscape of the United States for the duration of the flight.

When he landed, two FBI agents in black suits met him. They held up a sign that said “Hesham.” He put his luggage in the trunk and got into the back seat of the black sedan.

En route to the hotel, the agents talked about his testimony and asked him how he was feeling.

“I’m not too happy,” Hesham said.

“You need to loosen up,” one of the agents said. “Keep your head up, keep positive. Good things will happen. You’re doing the right thing.”

Hesham showed up for court the next morning. He met with the prosecutor, whose name he doesn’t remember, in an office at the courthouse. Hesham was shown on a computer a minute-long clip of Hani, who sported a lengthy beard, appearing in a video saying something in Arabic to the effect of “Hey everybody, ” before the prosecutor stopped the tape. Hesham said the voice sounded “funny.”

“I don’t recognize the voice,” he said.

The prosecutor was incensed.

“What do you mean?” the prosecutor asked. “You spoke to your brother ten years ago. You’re now going back on your word?”

“When I spoke to my brother, he said, ‘Hey buddy, how are you, how’s everything?'” Hesham said. “The voice on the tape doesn’t sound like the guy I talked to. The voice on the video is not the same voice. The way he talks sounds like an imam. Someone who likes to preach or give a lecture.”

When he testified before the grand jury a few hours later, Hesham was asked how many brothers and sisters he has, their names and which number sibling Hani is, and when he left Saudi Arabia. Hesham was also asked when the last time he spoke to Hani was, and he discussed the money Hani helped secure for him from his family.

Then the prosecutor cued up the videotape.

“Does that look like your brother?” he asked Hesham.

Hani’s beard, Hesham says, threw him off. So, as previously instructed by the FBI, he focused on Hani’s eyes. Hesham said that because he is still unsure the man in the videotape is truly Hani, he testified, “If I am not mistaken, that looks like my brother.”