Tamms Correctional Center on 200 Supermax Road, near the southern tip of Southern Illinois, may be as far from the hustling and bustling city of Chicago, with its constant city throb of noise, as you can get. And it’s likely that no one can feel the difference as much as its inmates.

The only supermax facility in Illinois, meaning it is the only prison built to keep the majority of its prisoners in isolation, Tamms prison was consigned for closure by the state’s governor in July.

But the battle between former prisoners, the families of those hurt by conditions at Tamms, anti-torture advocates, the union determined to keep its jobs and the state legislature struggling to contain costs continues to rage.

The story of Tamms is the story of something positive that may have come out of a recession, about what may be the last throes of the supermax movement, and what a campaign against torture accomplished in less than four years.

Behind the Walls of Tamms

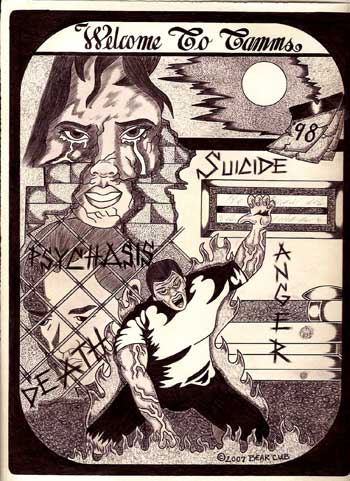

A man in Tamms made this drawing and others like it to communicate his despair from being in Tamms since 1998. (Image: Bear Cub)The first supermax prison in the United States was the infamous Alcatraz, opened in 1934. Since then, tough-on-crime policies have led to the opening of more than 55 correctional facilities devoted, entirely or partly, to housing “the worst of the worst” across the country. This was the logic behind the opening of Tamms in 1998.

A man in Tamms made this drawing and others like it to communicate his despair from being in Tamms since 1998. (Image: Bear Cub)The first supermax prison in the United States was the infamous Alcatraz, opened in 1934. Since then, tough-on-crime policies have led to the opening of more than 55 correctional facilities devoted, entirely or partly, to housing “the worst of the worst” across the country. This was the logic behind the opening of Tamms in 1998.

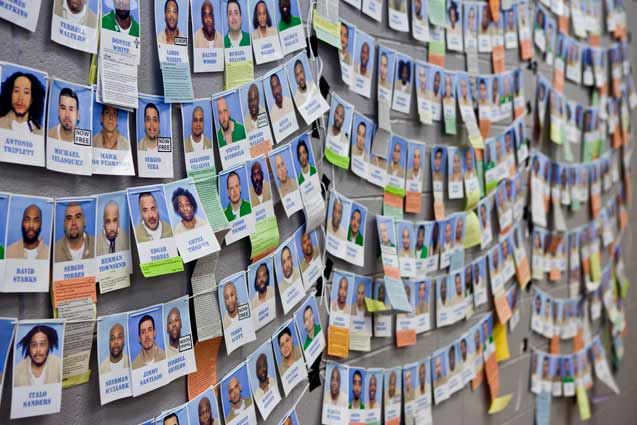

For the first ten years of its operation, the prison was mostly silent to the public ear. When the Tamms Year Ten campaign launched ten years after the prison was first opened, it became clear that much of the silence was due to the prolonged solitary confinement that most of its inmates were kept in for years.

“We wanted to create a set of demands around the crisis of isolation,” said Laurie Jo Reynolds with the Tamms Year Ten campaign. “The prison was started with the concept of short-term isolation, but ten years later, no one had heard anything from inside Tamms.”

The group, made up of former prisoners, prisoners’ families, artists, writers, lawyers and others, believes that long-term solitary confinement is a form of torture punishment that should be curtailed, if not banned altogether.

When they finally began hearing word from Tamms, the group discovered that most inmates are held in concrete cells 24 hours a day, are not allowed phone calls, and rarely see or speak to another human being. In addition, what little counseling was available was wholly inadequate, and reading material and family photographs were strictly rationed.

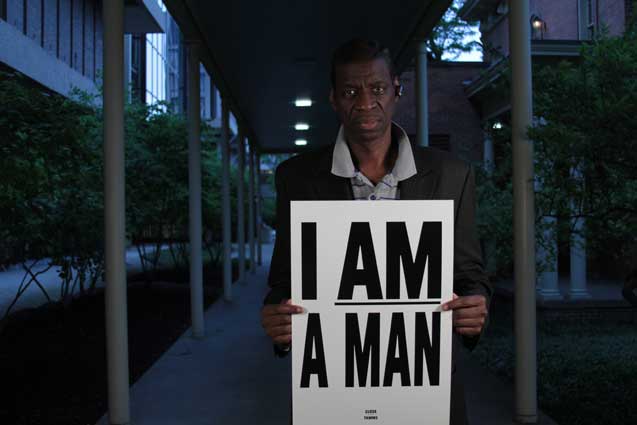

Darrell was tortured into a confession by Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge in 1983. Of his 24 years of wrongful imprisonment, the last 9 were spent in Tamms. (Photo: Community Based Art Practices Group, School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Tamms Year Ten)

Darrell was tortured into a confession by Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge in 1983. Of his 24 years of wrongful imprisonment, the last 9 were spent in Tamms. (Photo: Community Based Art Practices Group, School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Tamms Year Ten)

A former inmate, Brian Nelson, described the feeling of being in Tamms: “The doors are like a rust-red color with thousands of perforated holes. And you look outside, and you don’t see nothing but a gray wall. My biggest fear is that this is all happening in my head, and I am going to wake up and I’m in that cell. And that scares the s—- out of me.”

Reynolds says that half of the prisoners they communicate with are under administrative detention, meaning they could be alleged gang members or have other ties that cause them to be classified as “administrative detainees,” a category long considered “broad enough as to be meaningless.”

A report by the John Howard Association of Illinois found that:

Supermax inmates frequently suffer from mental illness. At Tamms, this often manifests itself in inmates cutting themselves, a practice staff tries but is unable to prevent. While Tamms has implemented some policies intended to lessen the harshness of life within its walls, it also has some practices certain to increase inmate discomfort….

The prison is intentionally devoid of color or other visual stimulation. Inmates are usually unable to talk with one another. At best, they spend 23 hours a day alone within their cells. At worst, they can be confined to their cells 24 hours a day for three months as a disciplinary measure. Like its counterparts around the nation, Tamms is frequently criticized for maltreatment of inmates. There are 23 pending federal lawsuits against Tamms, according to prison management. Earlier this year a federal judge ruled that inmates sent to Tamms could challenge their transfer to the prison. The judge concluded that conditions at the prison endanger the psychiatric well being of long-term inmates.

Reynolds says that a large majority of the prisoners have pre-existing mental health conditions, creating a cruel cycle. “When those people are in a regular prison, they can’t follow all the rules, but when they are placed in isolation, their mental health gets worse.”

More generally, Illinois correctional facilities regularly hold inmates who are mentally ill and end up in prison or jail for lack of treatment facilities that could help them avoid punishment. Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart called Cook County Jail “the largest mental health provider in the state of Illinois.”

In 2012, the United Nations discussed the possibility of launching a probe to see whether the treatment of inmates at Tamms constituted torture by international human rights standards.

But for those whose loved ones spend every day in Tamms, the pain continues.

Brenda Smith, whose son Herman has been in isolation in Tamms for more than ten years, says, “The letters that he writes me are horrifying.”

The only way she copes is by “trying not to think about what he is going through.”

“I am the only person he can write the letters to, and he doesn’t tell me everything he is going through,” says Smith.

Smith’s son is one of the inmates at Tamms whose distress has led him to self-mutilate.

“It’s like he’s dead, in a sense. You can’t touch him; you can’t hug him. It’s hard.”

Family members and other people of conscience hold a rally outside the James R. Thompson Center to urge Governor Quinn to recognize that long-term isolation causes lasting mental damage, and that people with extreme mental illnesses are more likely to end up in segregation and eventually isolation. (Photo: Tamms Year Ten)

Family members and other people of conscience hold a rally outside the James R. Thompson Center to urge Governor Quinn to recognize that long-term isolation causes lasting mental damage, and that people with extreme mental illnesses are more likely to end up in segregation and eventually isolation. (Photo: Tamms Year Ten)

The Roots of a Campaign Take Hold

Reynolds first met two mothers of prisoners at Tamms when she was working on a campaign against the high cost of phone calls in jails. The prison opened in 1998, and it was 2008 when Reynolds says that one-third of the more than 250 inmates in Tamms had been in solitary confinement for ten years.

She kept in touch with them, and then, in 2000, she joined several mothers and anti-prison activists on the Tamms Committee. From there, they launched the Tamms Poetry Committee, “By sending a poem or a letter to every person at Tamms,” said Reynolds, “we gave them much-needed human contact.”

One of the prisoners sent a poem back, and then, more prisoners sent poems back. And then they started asking something else, says Reynolds: “This is great, but could you please tell the government what is going on here.”

That was in 2007.

“It prompted us into launching a campaign,” said Reynolds. “I thought, if I find this so appalling and reprehensible, if we take this issue to the public, they will agree with us. It was the prisoners who prompted us to go further.”

Then began the legislative merry-go-round that the group has followed doggedly, now nearly to its end. The group started pressuring the Prison Reform Committee, an arm of the Illinois House of Representatives, to call a hearing.

And when they did, in 2008, “We held a series of events to prepare for the hearing, and then packed the room,” said Reynolds.

Riding the momentum from the hearing, Tamms Year Ten decided to push for reform legislation that Reynolds says would “go back to the original legislative intent” of the facility.

A key complaint of the men in the prison was that many of them were not aware why they were in the supermax facility, or what they needed to do to get out. The result was HB 6651, introduced in the spring 2008 session to establish standards for which prisoners could be transferred to Tamms and to set the limits of their stay.

According to Stephen Eisenman, a Northwestern University art professor and activist with the campaign, the bill would, “ensure that only violent prisoners are transferred to Tamms; provide hearings to establish fairness in decisions about transfer; limit terms of solitary confinement at Tamms to one year, unless the prisoner committed another violent act; and prevent mentally ill prisoners from being sent to Tamms.”

The legislation didn’t make it into law, but a new director, Michael Randle, was appointed to the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC), with the top priority of reviewing the supermax. He met with Tamms Year Ten and legislators and began looking into the conditions in the prison. This was in May 2009.

Meanwhile, the Belleville News-Democrat began a series in August 2009 that unveiled the horror behind the doors of Tamms: prisoners self-mutilating, the high proportion of mentally ill prisoners and the large costs of running the facility.

Tamms Year Ten continued to send letters and poetry to prisoners and to organize screenings, marches, music concerts and art campaigns.

Randle issued a Ten Point Plan for how to reform Tamms in 2010, calling for better mental health screenings, limited phone calls and the chance for prisoners to earn time outside of their cells. At the same time, a new process of prisoner reviews at Tamms led to the transfer of nearly 40 inmates out of the facility and the introduction of a new GED program.

Then in July of 2012, US District Judge G. Patrick Murphy ruled that several dozen individuals from Tamms had had their constitutional rights violated and were denied their right to a hearing before they were sent to the isolation facility, and called the incarceration at Tamms “virtual sensory deprivation.”

Eisenman, in an op-ed in The Chicago Sun-Times, argued that, while their efforts were welcomed, “neither Judge Murphy nor the John Howard Association got to the heart of the matter.”

The problem with Tamms is not that guards are insensitive, food is poor, educational programming – apart from a few GED classes – is nonexistent or rules for visitation are maddeningly complex. It is that terms of isolation are unconscionably long and that there is a lack of transparency concerning the reasons prisoners are sent to Tamms. Forty of the 206 men now at Tamms have been there since the facility opened in 1998, and criteria for being sent to the prison (and held there) are vague in the extreme…. [Legislators and Illinois Department of Corrections officials] should remember that the Ten-Point Plan at Tamms remains an incomplete project and that fundamental change at the Supermax is essential for the sake of economic health, public safety and basic humanity.”

On September 2, 2010, the group lost its sympathetic director when Randle resigned following a scandal in which prisoners let out on an early-release initiative he championed re-offended soon after their release.

Tamms Year Ten has continued to testify every year to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees when the IDOC budget is being argued.

“The financial argument itself is so striking, it would be easy to close the facility on that only,” said Reynolds.

The Straw That Broke the Camel’s Back

On June 19, Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn announced that Tamms would be closing by the end of August.

Along with years of work by activists, the straw that broke the camel’s back and led to the planned closure was price tag. The cost to run Tamms, which regularly holds less than 200 prisoners at a time, is $62,000 per inmate per year. According to NPR, this is three times the statewide average.

Quinn said in a statement: “We have the responsibility to manage the state’s limited resources as efficiently as possible and make the difficult decisions necessary to restore fiscal stability to Illinois. The growing costs of pension and Medicaid make up 39% of state general revenue spending. While we were able to enact more than $2 billion in Medicaid reforms with bi-partisan support, we still must reform our public pension systems to alleviate this squeeze on general revenue spending.”

Annually, the cost to run the facility is $26 million, out of the IDOC’s $1.2 billion budget.

Meanwhile, Illinois’ budget deficit is one of the worst in the nation – $43.8 billion in the red. Child care programs, health care for low-income people, programs for the homeless and public-sector pensions have all ended up on the chopping block.

The Tamms Year Ten campaign celebrates the decision, says Reynolds. “It was a pragmatic decision, but I think Quinn is also principled and cares about the issue.”

Reynolds says that the new IDOC director says only 25 individuals in Tamms are in need of maximum security. Some prisoner transfers have already begun.

For Smith, whose son remains in Tamms, the news of the closure “is something to give them hope.”

“They would have a lot less problems if they were giving them any hope, but they see no way out,” said Smith. “If you cage an animal up and mistreat him, he will bite you.”

Downstate legislators and the prison union have come down hard against the closing of the prison. It is the main employer in Tamms, Illinois, a town with a population of 632.

Legislators, including some Democrats, have continued to put money to run Tamms into the Department of Corrections budget, which Governor Quinn has then vetoed as a line item.

Illinois Rep. Brandon Phelps (D-Harrisburg), one of the Democratic legislators leading the push to keep Tamms open, was not available for comment.

Prison guards, led by American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Local 31, are suing Governor Quinn for his plans to close the facility, arguing that bringing Tamms residents to other prisons will increase overcrowding and bring unsafe working conditions.

Reynolds, in response, says that guards from Tamms could be used to staff other overcrowded and understaffed prisons. “The union has gone entirely ballistic with a campaign of outright lies, half-truths and fearmongering,” she said.

AFSCME Local 31 did not respond to requests for comment.

But the lawsuit, and a criminal investigation into alleged leaks by prison guards, has halted prisoner transfers until August 17.

Eric Fink, a labor lawyer, professor and former legal attorney for AFSCME prison guards in Pennsylvania, says that the tension between a union’s immediate employment interests and a wider social justice agenda is not unheard of.

“The union’s main function is to advocate for the interest of its members, and it isn’t normally in the business of saying we support eliminating the jobs of our members.”

However, says Fink, “the ideal solution might be to say, for reasons of social justice, that we agree with reigning back the prison complex, but we want that to be coupled with shifting to other jobs and the necessary training so correctional officers can be trained to do other things.”

Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1000 in California has come out against prison expansion in favor of increasing positions for social workers instead.

The End of Supermax?

Despite the roadblocks, Reynolds says she is “confident the closure of Tamms – a really difficult project, but also a really inspiring project – will be completed.”

And with it, says Reynolds, another leg will be kicked out from under the supermax model. States including California and Kansas have closed or downgraded their maximum-security prisons.

However, the battle continues. On August 17, Quinn is expected to announce the results of his discussions with AFSCME, and as the Tamms issue continues, he is under fire for not letting reporters into two other Illinois prisons where, inmates say, conditions are poor.

For Reynolds, “the moral of the story is, it really does matter if a bunch of people band together and say, You can’t do this.”

Interviews by Vocalo

Music Vox host Jesse Menendez spoke with Tamms Year Ten representative Josh Jones about his organization’s efforts to close the Tamms Correctional Center and the benefit Tamms Year Ten is organizing to support their cause.

Josh Jones on Vocalo.org 89.5

The Tamms Year Ten benefit is bringing together progressive artists like Kool A.D from Das Racist, Fat Tony, BBU and others in support of their efforts to close Tamms Correctional Center. BBU members, Esquire, Illekt and Epik joined Jesse Menendez to discuss the human right violations at Tamms Correctional Center and music and its role in activism.

The MusicVox – BBU on Tamms on Vocalo.org 89.5

Angry, shocked, overwhelmed? Take action: Support independent media.

We’ve borne witness to a chaotic first few months in Trump’s presidency.

Over the last months, each executive order has delivered shock and bewilderment — a core part of a strategy to make the right-wing turn feel inevitable and overwhelming. But, as organizer Sandra Avalos implored us to remember in Truthout last November, “Together, we are more powerful than Trump.”

Indeed, the Trump administration is pushing through executive orders, but — as we’ve reported at Truthout — many are in legal limbo and face court challenges from unions and civil rights groups. Efforts to quash anti-racist teaching and DEI programs are stalled by education faculty, staff, and students refusing to comply. And communities across the country are coming together to raise the alarm on ICE raids, inform neighbors of their civil rights, and protect each other in moving shows of solidarity.

It will be a long fight ahead. And as nonprofit movement media, Truthout plans to be there documenting and uplifting resistance.

As we undertake this life-sustaining work, we appeal for your support. We have 7 days left in our fundraiser: Please, if you find value in what we do, join our community of sustainers by making a monthly or one-time gift.