Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

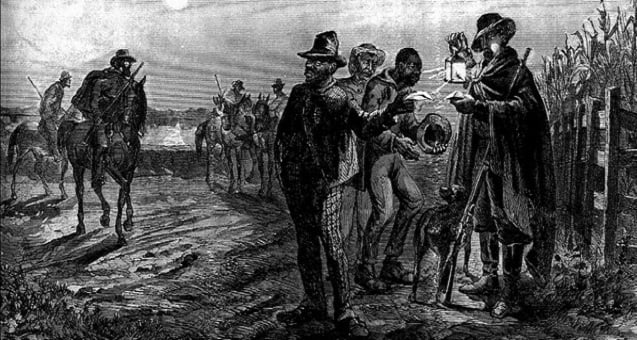

Patrick Feller / Flickr)” width=”637″ height=”340″ />Slave Patrols, the militias of the Second Amendment. (Image: Patrick Feller / Flickr)

Patrick Feller / Flickr)” width=”637″ height=”340″ />Slave Patrols, the militias of the Second Amendment. (Image: Patrick Feller / Flickr)

George Zimmerman kept close watch over his neighborhood.

When Black men walked or even drove through the area, he alerted the police, over and over and over again.

Finally, exasperated that “they always” got away, he went out on a rainy night armed with a loaded gun and the Stand Your Ground law, looking for anybody who should not be in his largely White neighborhood.

The South has a long history of this sort of thing. Today they’re called Neighborhood Watches. They used to be called Slave Patrols.

Prior to the Civil War and Reconstruction, the main way Southern states maintained the institution of slavery was through local and statewide militias, also known as “Slave Patrols.” These Patrols were, in many states, required monthly duty for southern white men between the ages of 17 and 47, be they slave-owners or not.

Slave patrollers traveled, usually on horseback [the modern equivalent would be in a car], through the countryside looking for African-Americans who were “not where they belong.” When the patrollers found Black people in places where they “did not belong,” punishment ranged from beatings, to repatriation to their slave owners, to death by being whipped, hung or shot.

Some of the most comprehensive reports on the nature and extent of the Slave Patrols came from interviews done by the WPA (the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal program created by FDR) during the Great Depression. At that time, former slaves and the children of former slaves were still alive and had stories to tell, and the WPA put people to work in the American South gathering and documenting those stories.

The WPA’s Georgia Writers Project, Savannah Unit, produced a brilliant summary of stories taken from people who were alive (most as children) during the time of slavery, about their and their families interactions with slave patrollers. The report’s title was “Drums and Shadows: survival stories among the Georgia coastal Negroes,”

Many other oral and written histories compiled by the WPA Writers Project are now maintained by the library of Congress.

Dozens of other similar reports, as well as detailed state-by-state studies of slave patrols, even including membership rosters, are published in Sally E. Hadden’s brilliant book “Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas.”

Hadden cites numerous stories and scores of sources about how the slave patrollers would beat, whip, or otherwise abuse African-Americans who were found off the plantation. Women were routinely subjected to rape, and men were usually beaten with sticks or whips. Hadden writes of the stories compiled by the WPA:

“Slaves might beg to be left out of a whipping from the patrol, hoping that mercy or caprice might avert a beating. Patrollers sometimes toyed with a slave, threatening a whipping, then let the slaves go free. The inherent arbitrariness of punishment added to the fear most slaves felt when they encountered slave patrols.”

“One former bondsmen [slave], Alex Woods, recalled how a patrol reacted to a begging slave. He said that the patrollers ‘wouldn’t allow [slaves] to call on de Lord when dey were wippin’ ‘em but they let ‘em say, “Oh! pray, Oh! pray, marster.”’

“The harsh punishment a patrol could administer caused one former slave to like meeting the patrol with being sold to a new master – a slave would seek to avoid both fates at any cost. Few things compared to the agony a slave endured from a patroller beating. One ex-slave from South Carolina recalled what people heard when she was born: her mother ‘screamed as if she were being beaten by patrollers.’”

The National Humanities Center reprinted an 1857 account by Austin Steward, who escaped slavery in 1813. Titled “Slaves and Slave Patrol,” Steward opens the account with this summary:

“Slaves are never allowed to leave the plantation to which they belong, without a written pass. Should anyone venture to disobey this law, he will most likely be caught by the patrol and given thirty-nine lashes. This patrol is always on duty every Sunday, going to each plantation under their supervision, entering every slave cabin, and examining closely the conduct of the slaves; and if they find one slave from another plantation without a pass, he is immediately punished with a severe flogging.”

He then goes on to tell several harrowing stories of personal encounters with the slave patrol, including one that led to the death of six slaves, and reprints the North Carolina Slave Patrol regulations as follows:

SLAVE PATROL REGULATIONS, ROWAN COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA, 1825

1st. Patrols shall be appointed, at least four in each Captain’s district.

2d. It shall be their duty, for two of their number, at least, to patrol their respective districts once in every week; in failure thereof, they shall be subject to the penalties prescribed by law.

3d. They shall have power to inflict corporal punishment, if two be present agreeing thereto.

4th. One patroller shall have power to seize any negro slave who behaves insolently to a patroller, or otherwise unlawfully or suspiciously; and hold such slave in custody until he can bring together a requisite number of Patrollers to act in the business.

5th. Previous to entering on their duties, Patrols shall call on some acting magistrate, and take the following oath, to wit: “I, A. B. appointed one of the Patrol by the County Court of Rowan, for Captain B’s company, do hereby swear, that I will faithfully execute the duties of a Patroller, to the best of my ability, according to law and the regulations of the County Court.”

The National Humanities Center has many other similar reports in its archives.

Slave Patrols were a regular feature of the South, from its first settlement by slave-owning Europeans until the decades after Reconstruction.

When slavery was abolished, but Whites in the South still wanted to keep Blacks “in their place,” the Slave Patrols were largely replaced by (or simply renamed as) the KKK, small-town sheriffs, stop-and-frisk policies, and, apparently, “Neighborhood Watch.”

Slave Patrollers rarely stopped or molested white people. But when Blacks were found in unexpected places, they could expect a swift and severe punishment.

And the legal systems of the South, largely without exception, backed up the Slave Patrollers and their post-reconstruction heirs.

It appears that the more things change – at least in the deep South – the more they stay the same.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 310 new monthly donors in the next 4 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.