This is the second piece of a four-part investigative series on the Chicago Police Department and the Independent Police Review Authority. See also Part I, Part III and this supplement.

Among the few decipherable details of the police shooting of her 14-year-old son, Laura Rios related two stark facts she revisits time and again. “Pedro was a little kid and he died alone,” she said, speaking with Truthout by way of an interpreter.

Gazing at a wall in the family’s living room, Rios looked at her second-eldest child’s last school photo. With younger brothers playing video games below, the boy smiled back from beneath cap and gown, posed for his eighth grade graduation portrait.

“There has to be justice,” Rios said. “That’s all I want. That’s all my husband wants.”

“You never know what can develop in the life of a young person when they’re no longer with you.”

On the same wall, younger versions of the couple can be found, captured at the annual holiday party of the luxury hotel where Pedro Rios Sr. has worked for 25 years. While their hairstyles and fashions change throughout the years, they appear always as a handsome couple, smiling, framed amid photos of the family in happier times.

The pair met in Chicago, but happen to hail from the same seaside state of Guerrero, Mexico, where parents of 43 students abducted by police, in collusion with the capital’s mayor, have commanded international attention in the months since Rios was killed. Unwilling to assume their children are dead, the Guerrero parents’ demand is simple: that the state must conduct a thorough investigation.

Two thousand miles away from Guerrero, Laura Rios remembered, “I thought it was going to be great, raising a family here. But, I see now that’s not the case.”

Pedro Rios Sr. and Laura Rios in the aftermath of their son’s death. (Courtesy of Benjamin Woodard, DNAInfo.com Chicago)

Pedro Rios Sr. and Laura Rios in the aftermath of their son’s death. (Courtesy of Benjamin Woodard, DNAInfo.com Chicago)

“What hurts me the most is that my husband has worked hard for so many years and I’ve worked hard – two jobs for 15 years,” Rios said. “All to give our children the best we could. Then Pedro was taken away from us just like that.”

“He was always laughing and smiling, and he helped me a lot in the house,” she said. It was assistance that occasionally took the form of ordering his little brothers around, Rios remembered, smiling while slipping into an impression of her son. “‘Do this, now. Put that, there. You have to help mom,'” she said, finger pointing along to the same rhythm as commands.

Big-brother bossiness aside, one word came up time and again among the after-school educators who knew Pedro Rios Jr. during various parts of his childhood. “He was a sweet little boy.” “He had a sweet smile.” “He was always so sweet.”

Rios, bottom left, taking part in the creation of a community mural in 2008. (Courtesy of Christine Malesky)

Rios, bottom left, taking part in the creation of a community mural in 2008. (Courtesy of Christine Malesky)

A breakdancing natural, Rios painted murals and participated in arts-oriented community programs in his neighborhood throughout childhood. While the years went by, the boy’s modes of expression grew as he did: co-writing and starring in a short horror film at 10; launching a YouTube channel where he reviewed game systems and gadgets at 11; learning photography during the summer and playing basketball during the winter at 12.

“You never know what can develop in the life of a young person when they’re no longer with you,” said Justin Grey, a community educator who first taught Rios as a 6-year-old in hip-hop arts camp. “But, the news came as a shock.”

“This kid was like an angel. He was a family type of kid, even in programs,” Grey remembered. “You could always see him glance over to the younger kids, checking on his brothers.”

Tom Callahan, a photographer, taught the last after-school program Rios attended at 12. “You know those kids who can make people laugh? Pedro was the kid who could make people smile,” Callahan said. “He seemed to have the kind of self-confidence that didn’t need a lot of words.”

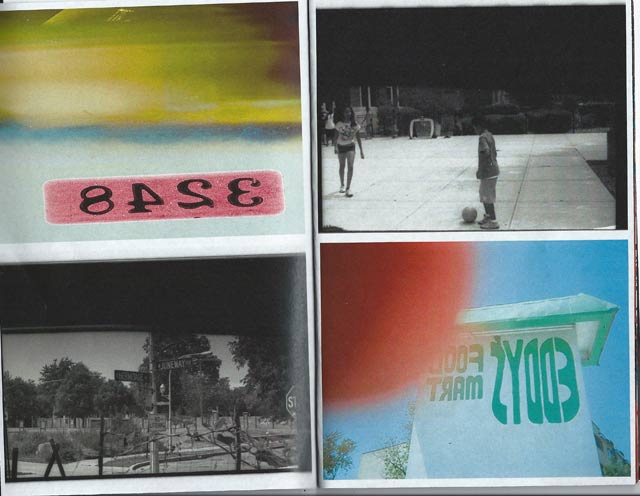

It was a trait that lent itself to the young photographer’s aesthetic, the teacher remembered, when the program culminated in the production of a zine highlighting student work. “Pedro’s layout was unique. He knew exactly what he wanted to do. He had this bold, experimental style. It stuck with me,” Callahan said.

Images from the Casting Shadows Photography Club zine “Magazone,” with art direction and photography by Pedro Rios Jr. (Courtesy of Tom Callahan)

Images from the Casting Shadows Photography Club zine “Magazone,” with art direction and photography by Pedro Rios Jr. (Courtesy of Tom Callahan)

In the last two years of his life, which followed, Rios spent stints of time as a paid barber and volunteer bike mechanic. With professional clippers gifted by his parents, the boy had years of experience stylizing fade haircuts for his brothers and friends by the time he entered his teens. But, after taking regulars at the barbershop around the corner from the family’s apartment, Rios eventually gave up his first profession. As one of his little brothers explained, the cost of renting the barbershop chair meant the teen only broke even more often than not.

Rios was an exceptional, industrious child, but also shared the interests and flaws of many of his peers. “He liked sports. He liked his bike. He liked music. He liked shoes,” Rios’ father told a neighborhood reporter after the shooting. In its wake, the devastated family also mentioned a rebellious streak that had recently been developing in Rios, who was spending increasing time with a crowd that raised their concerns. Two weeks before their son’s killing, the parents sought out the help of police, with the boy’s safety in mind. Eager to get Rios back on track, after he stayed out for so long once they filed a missing persons report, Laura Rios inquired with authorities on boot camps, and described being met with indifference and given zero referrals. Pedro Rios Sr., meanwhile, began talking to his namesake about finishing school in Mexico.

Justifying Deadly Force

What followed was a nightmare. According to the police account, as delivered by Chicago Police Superintendent Gary McCarthy in a public statement justifying each of the eight police shootings that took place the July 4, 2014, weekend, Pedro Rios Jr. ran from a police officer and pointed a weapon, prompting the officer to fire.

At 14-years-old, he died in an alley, shot twice in the back, alone.

Despite the superintendent’s assertion otherwise, the parents were shocked.

“Why couldn’t they detain him?” Laura Rios asked.

Although authorities possess a surveillance video – and dash cam footage of Rios’ shooting should exist, per the police narrative placing the incident in proximity of a squad car – they have not released either for public viewing. We have no way of knowing whether or not the teen had a gun, or aimed one at an officer – particularly in a city where a federal jury concluded Chicago police officers planted a gun in the 2003 shooting death of Cornelius Ware. A 20-year-old paralyzed Black man, Ware could not comply with officers’ commands to exit his vehicle. He sustained gunshot wounds to both hands, which were held in the air per police orders when the shooting occurred, according to three eyewitnesses. But according to police, Ware allegedly pointed a weapon. A gun was recovered without fingerprints or blood, after the paramedic who treated Ware inside his car observed that there was no firearm present. The City of Chicago settled the case for $5 million.

For every 6 million civilians policed in 2014, one officer fatality from civilian gunfire occurred.

Fast-forward to 2014: A month before the killing of Michael Brown (the 18-year-old Black youth shot by police in Ferguson, Missouri), Chicago Police union spokesperson Pat Camden justified Rios’ shooting to media in the hours between his death and that of 16-year-old Warren Robinson the next day. “You put your hands in the air, I guarantee you, you will be fine,” said Camden, who was deputy director of Chicago Police News Affairs at the time of Ware’s killing.

The police spokesman also justified the killing of 17-year-old Christian Green one year prior; the boy was shot in the back on July 4, 2013. In Camden’s account, the Black teen ran from police and then stopped to point a weapon at pursuing officers.

According to the Independent Police Review Authority’s investigation, a video exists in which the boy is seen attempting to throw a gun away while running from police. There is no proof cited, beyond the involved officers’ statement, that the weapon was pointed at police. Robinson, meanwhile, reportedly ran from officers who claim to have begun their pursuit because the teen matched a description. While crawling out from beneath a car they had surrounded, Robinson allegedly pointed a gun, according to police – an account disputed by eyewitnesses.

Given the prevalence of the police allegation, and the high-profile killing of two New York City police officers in late 2014, Truthout spoke with Loyola University criminologist and clinical psychologist Dr. Art Lurigio to garner insight on civilian gun threats to police.

“My main concern as a mother is that no child deserves to be shot in the back by anyone.”

“It’s a rare event,” the criminologist explained. “It’s not a trivial amount, but the impression in the general public is that incidents of police being shot at are much more common than they are. If you see something often in news and movies, you will overestimate the frequency in which it occurs.”

“Most of the people of a community are not shooters and are not gang members. Even most gang members are not shooters,” Lurigio said. “It is a very small percentage of people who might engage in violence.”

According to the Officer Down Memorial Page, 41 officers were killed by gunfire across the United States in 2014: Not an insignificant number, as Lurigio pointed out. But among the vast population with whom police interact, the number paints a picture of relative safety.

Commenting at a 2012 Use of Force policy symposium, Louis Dekmar, chief of police in LaGrange, Georgia, said, “Recent police deaths are tragic but the most violent year for police occurred in 1971. We need to take … data and examine it historically rather than take it raw and think we are under siege. Without proper analysis there is fear that is unwarranted.”

In Truthout’s analysis, for every 6 million civilians policed in 2014, one officer fatality from civilian gunfire occurred. (1)

Asked about the likely factors leading to the rare instance in which a civilian does pull a gun on a police officer, Lurigio explained, “It’s an extreme act, in the sense that the person doing so is putting their life in obvious peril, in that it’s the ultimate threat to the ultimate authority on the street…. A person pulling a weapon on police would have been involved in many high-risk situations, in which the situation unfolding is just another. They’re not thinking beyond the moment.”

Usually, Lurigio noted, the person pulling the gun is a young man. Yet the portrait does not otherwise align easily with shooting victims such as Rios, Green and Robinson, who reportedly fled perceived peril, while officers pursued it, later citing fear for their lives.

Killed by gunshots to the back and/or while laying face down, the teens’ deaths are not aberrations. Among the 10 fatal shooting cases most recently closed by the Independent Police Review Authority, three occurred under similar dynamics – and were deemed “justified.”

“No Child Deserves to Be Shot in the Back by Anyone”

Transcending the question of a weapon altogether, Patricia Green shared a moral imperative following the shooting of her son Christian, a high school senior.

“My main concern as a mother is that no child deserves to be shot in the back by anyone,” she told media.

One year to the day after her son was killed, a police officer shot 14-year-old Rios twice in the back.

Tom Callahan, the boy’s former photography teacher, was devastated by the news of his student’s death and the tone of public conversation in the shooting’s aftermath. (Beyond the police statement, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel weighed in on the violence of that July 4th weekend, saying, “A lot of people will say ‘Where were the police? What were the police doing?’ and that’s a fair question, but not the only question. Where are the parents?”)

“It’s shocking how people respond to the death of young people,” Callahan said. “I honestly don’t even think it matters if Pedro had a gun. That’s missing the point of the situation.”

Perhaps controversial to some, Callahan’s comment alludes to the simple fact that any given officer’s perception of the severity of a threat and the means necessary to neutralize it is subjective.

“Recruits are trained to recognize and react to a movement that looks like a gun being drawn.”

Conceal and carry gun laws codify the fact that possession of a firearm alone cannot be grounds for shooting. Meanwhile, Chicago neighborhoods where many police shootings take place are those that have been systematically abandoned by city planners – with the absence of jobs, closing of schools and historic disinvestment leaving little left but an informal economy of which guns are a part.

Regarding the use of deadly force against civilians, police officers are afforded broad latitude – assumed a necessity given the split-second decision-making required in all situations of grave danger – paving the way for the exoneration of shooting officers in even the most questionable of killings.

Yet clearly, such circumstances are the exception and not the rule. Meanwhile, the Secret Service and four of the 10 most competitive economies in the world – Finland, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom – demonstrate success with minimal to nonexistent use of deadly force.

In addition to these international models, Dr. Richard David, an intensive care pediatrician and public health researcher, points to a key historical precedent. “For as long as there’s been human society, we’ve always given the young people special care and a little slack,” he said. “All that is based on enormous tradition.”

“An Automatic Reaction Without Thought”

But with officers logging hundreds of hours in physical and video simulations, in which they face mortal danger at the hands of civilians and must quickly kill or be killed, US law enforcement training on the use of deadly force makes no allowances for youth, or anyone else perceived as a threat.

“The threshold that’s crossed is taking the weapon out,” said criminologist Art Lurigio. “Practice targets do not include arms and legs. It’s the torso and the head with the bull’s-eye in the middle. Those are deadly shots and that’s what police practice a thousand times.”

“It becomes an automatic reaction without thought,” analogous to basketball players’ free throws, he explained. “If officers think, if they hesitate, they are not going to precisely execute a practiced behavior.”

Chicago Police spokespeople did not respond to Truthout’s request for comment on the department’s training practices. However, recent reports of mainstream journalists, observing and participating in deadly force trainings – to the point of firing on simulated civilians in virtual and role-play scenarios – offer a glimpse inside the thinking cultivated in officers.

“Recruits are trained to recognize and react to a movement that looks like a gun being drawn,” described a San Diego journalist, who was told by a training officer, “They’re taught from Day One the hands are what’s going to kill you.”

“I got grandkids I’ll have to sit down and tell what happened, when they’re old enough. I got a son that I’ll never see again.”

Halfway across the United States, in the state capital of Springfield, Illinois, an evening news reporter characterized authorizations to use force as determined “not by what’s right, but what’s reasonable,” after a simulated encounter with a suicidal woman. “I think you have to give her the opportunity to put the gun down,” the journalist said, when asked by the instructor to guess the appropriate amount of time to wait before shooting the woman. “It doesn’t take very long for that gun to go from here to here,” the instructor said, pointing to his head and then the young journalist. “It’s a natural inclination … to try to talk her out of that, so under our policy you would have been authorized to actually use deadly force.”

Back in Chicago, officers undergo 900 to 1,000 hours of deadly force role-play training before placement on the streets, according to a 2011 news segment featuring a correspondent who “fired” on two civilians reaching for cell phones, in the course of participating in the simulation.

“It helps them and inoculates them to stress,” a Chicago Police instructor told the reporter.

But in its publication, “Principles of Good Policing,” the Department of Justice quotes a report of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, “Balance of Forces,” offering a warning on the approach as of 1982.

“In-service crisis intervention training as opposed to pre-service training was associated with a low justifiable homicide rate by police,” the report notes. “Agencies with simulator, stress, and physical exertion firearms training experience a higher justifiable homicide rate by police than agencies without such training.”

Racism in the Application of Deadly Force

Early this year, a member of the Florida Army National Guard stumbled upon a frightening symptom of another consistent pattern in the real-world application of deadly force: racism.

At a shooting range, the guardswoman found a bullet-riddled photo of her younger brother, alongside images of other Black men, pinned to targets by North Miami Beach Police.

“The city can’t let police keep killing our kids and keep getting away with it. It’s already too late.”

One month later, on Valentine’s Day, a pair of Chicago police-involved shootings took place. In the predominately White neighborhood of Andersonville, a 33-year-old White man disarmed a police officer, reportedly then firing the gun at the officer and his partner multiple times. The man was taken into custody without injuries cited. Across town, in the predominately Black neighborhood of Englewood, an 18-year-old was reportedly taken to the hospital in “serious condition,” shot multiple times after allegedly “pulling a gun out of his sweater” while officers surrounded him, according to Fraternal Order of Police spokesman Pat Camden.

Taken beyond a single day, the life-and-death racial disparities in how policing is practiced remain clear. Black Chicagoans are 10 times more likely to be shot by police than their White counterparts – comprising over 10 percent more of the city’s population, comparing US Census data and Independent Police Review Authority statistics.

In November 2014, a delegation of youth of color from Chicago brought evidence of such disproportionate targeting to the United Nations Committee Against Torture, in Geneva, Switzerland. Roused by the delegates’ unflinching presentation, the UN committee named the Chicago Police Department in its summary report, citing “deep concern” at “the reported current police violence in Chicago, especially against African-American and Latino young people … and recurrent police shootings or fatal pursuits of unarmed Black individuals.”

“What Is It Going to Take for Them to Stop Killing Our Kids?”

Ronald “Ronnieman” Johnson (December 14, 1988 – October 12, 2014) with his mother, Dorothy Holmes at her 2012 wedding. (Photo courtesy of Dorothy Holmes)Back in Chicago, months later, Mayor Rahm Emanuel was recently scheduled to meet with a different delegation – a cohort of parents whose children have been shot and killed by police in recent years. The mayor did not show, the parents learned upon arriving to City Hall.

Ronald “Ronnieman” Johnson (December 14, 1988 – October 12, 2014) with his mother, Dorothy Holmes at her 2012 wedding. (Photo courtesy of Dorothy Holmes)Back in Chicago, months later, Mayor Rahm Emanuel was recently scheduled to meet with a different delegation – a cohort of parents whose children have been shot and killed by police in recent years. The mayor did not show, the parents learned upon arriving to City Hall.

Among them was Dorothy Holmes, whose 25-year-old son Ronald “Ronnieman” Johnson was shot and killed by police on October 12, 2014. She spoke to Truthout by phone, after returning from the cemetery to place flowers on her son’s unmarked grave.

“I’m still in disbelief. But, I know Ronnieman’s gone,” Holmes said.

“I have my days where I break down. Sometimes it gets real difficult,” she said, her voice catching. “I’m trying to take it one day at a time … Ain’t really no other way to deal with it. I got grandkids I’ll have to sit down and tell what happened, when they’re old enough … I got a son that I’ll never see again.”

Born and raised on the far south side of Chicago, like his mother, Johnson was so fond of his two dogs he became known around his neighborhood as “the Dog Man,” Holmes told Truthout.

Johnson’s cemetery plot, awaiting the headstone for which the family is saving money. (Photo courtesy of Dorothy Holmes)Doing his dreadlocks a last time at the funeral home with other family members, she described finding gunshot wounds in the back of her son’s head, in his neck and the palm of his hand.

Johnson’s cemetery plot, awaiting the headstone for which the family is saving money. (Photo courtesy of Dorothy Holmes)Doing his dreadlocks a last time at the funeral home with other family members, she described finding gunshot wounds in the back of her son’s head, in his neck and the palm of his hand.

“What are you shooting at me for?” Johnson asked police, a bystander related to his mother afterward. Now, she has a question of her own.

“What is it going to take for them to stop killing our kids?”

“The mayor was a coward; he couldn’t face us. When his own son was robbed, that stayed in the news until they found someone. But, all these police shootings … they don’t care about none of that,” she said.

“The city can’t let police keep killing our kids and keep getting away with it. It’s already too late.”

On the opposite side of town, Laura Rios mirrored Holmes’ outrage. “These people … I don’t know if they have children or not. But they don’t seem to know or care about the pain of what it is to lose one.”

The Mayor’s Office of Rahm Emanuel did not respond to request for comment. It is worth noting that his opponent in Chicago’s mayoral run-off election, Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, advocates the hiring of an additional 1,000 police officers.

In the next installment of this series, Truthout will continue its investigation of the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA), the agency responsible for handling police misconduct allegations, weapon discharge notifications and officer-involved shootings. IPRA has referred the investigation of the shooting of Ronald Johnson to Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, whose office has not responded to request for comment and is in noncompliance with the Illinois Freedom of Information Act – as is the Chicago Police Department – requiring response in five working days. IPRA meanwhile has denied Truthout’s FOIA request for one month of its referrals to the Chicago Police Department, its 10 most recently closed death-in-custody case files, and specific month samples of complaints.

Alex Cachinero-Gorman contributed interpretation services to this report.

Footnote:

1. Sources and methodology: 2014 officer gunfire fatalities were culled from the Officer Down Memorial Page for all states, and filtered to separate officers working in Forest Service, Navy and in Puerto Rico, and to remove canine entries. The 2014 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) population figure of 249 million non-institutional civilians, defined as “persons 16 years of age and older residing in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, who are not inmates of institutions (e.g., penal and mental facilities, homes for the aged), and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces,” was adjusted downward to account for the police, subtracting Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) data on full and part-time sworn officers in 2008, gathered in a survey conducted every four years for which 2012 is not yet available; at 809,000 it is a conservative estimate given long-term BLS growth projections for the profession.

Angry, shocked, overwhelmed? Take action: Support independent media.

We’ve borne witness to a chaotic first few months in Trump’s presidency.

Over the last months, each executive order has delivered shock and bewilderment — a core part of a strategy to make the right-wing turn feel inevitable and overwhelming. But, as organizer Sandra Avalos implored us to remember in Truthout last November, “Together, we are more powerful than Trump.”

Indeed, the Trump administration is pushing through executive orders, but — as we’ve reported at Truthout — many are in legal limbo and face court challenges from unions and civil rights groups. Efforts to quash anti-racist teaching and DEI programs are stalled by education faculty, staff, and students refusing to comply. And communities across the country are coming together to raise the alarm on ICE raids, inform neighbors of their civil rights, and protect each other in moving shows of solidarity.

It will be a long fight ahead. And as nonprofit movement media, Truthout plans to be there documenting and uplifting resistance.

As we undertake this life-sustaining work, we appeal for your support. We have 10 days left in our fundraiser: Please, if you find value in what we do, join our community of sustainers by making a monthly or one-time gift.