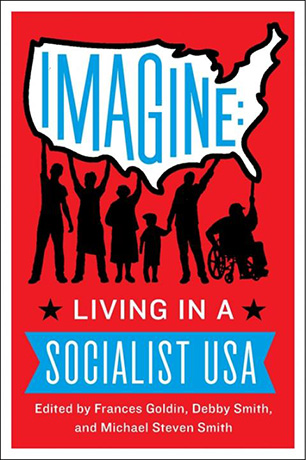

More than 30 top progressive thinkers have joined together to Imagine Living in a Socialist USA, a new book from HarperCollins edited by Frances Goldin, Debby Smith and Michael Steven Smith. Get the book now from Truthout for a minimum contribution of $25. Just click here for this roadmap to a socialist America.

The following is a chapter by retired education professor William Ayers from the anthology. In it, Ayers advocates replacing a capitalist-oriented educational system with one that liberates students and their intellectual and creative capabilities.

From Imagine Living in a Socialist USA:

Analogy Test

Multiple Choice

High-stakes standardized testing is to learning as:

a. Memorizing a flight manual is to flying

b. Watching Hawaii Five-0 is to doing police work

c. Exchanging marriage vows is to a successful marriage

d. Reading Gray’s Anatomy is to practicing surgery

e. Singing the national anthem is to good citizenship

f. All of the above

The typical American classroom has as much to offer an inquiring mind as does:

a. A vacant lot

b. A mall

c. A street corner

d. The city dump

e. The custodian’s closet

f. none of the above

The answer to each is “f” – in the first question for obvious reasons, and in the second because each of the other answers offer much more to an inquiring mind.

Capitalist Education: Into the Wreckage

Schools serve societies, and every society is reflected, for better and for worse, in its schools. Every school is both a mirror of and a window into the defining social order. If one looks at the schools hard enough, one can see the whole of the larger society; if one fully grasps the intricacies of society, one will know something about how its schools must be organized, and why.

In a totalitarian society, schools are built to teach obedience and conformity, plain and simple. In a kingdom, schools teach allegiance to the crown. An ancient agrarian community apprentices the young to become participants in a rustic world of farming. With a theocratic regime come lessons in faithfulness and piety and devotion.

These schools might be “excellent” by some standards or measures, but whatever else is taught – math or music, literature or science – the most important lessons are those that teach how to function in a specific social order. South Africa under apartheid had beautiful palaces of learning and small state-of-the-art classes for white kids – and overcrowded, dilapidated, ill-equipped classes for the African kids. That made perfect, if perverse, sense: privilege and oppression were on opposite sides of the color line, and everyone understood that hard, cruel fact. German schools in the early twentieth century produced excellent scientists, athletes, artists, and intellectuals, and they also produced submission and conformity, moral blindness, obtuse patriotism – and people for whom a pathway straight into the furnaces for some of their fellow citizens seemed acceptable.

In our capitalist society, we are insistently encouraged to think of education as a product like a car or a refrigerator, a box of bolts or a screwdriver – something bought and sold in the marketplace like any other commodity. The controlling metaphor is that the schoolhouse is a business run by a CEO: the teachers are the workers, and the students are the raw material bumping along the assembly line, getting information stuffed into their little upturned heads.

Within this model, it’s easy to believe that downsizing the least productive “units” and privatizing a space that was once public is perfectly natural. It’s also easy to think that teaching toward a simple standardized measurement and relentlessly applying state-administered (but privately developed and quite profitable) tests to determine the “outcomes” are a rational proxy for learning.

It’s easy to think that “zero tolerance” for student misbehavior is a sane stand-in for child development or justice. And it’s easy to think that centrally controlled “standards” for curriculum and teaching are commonsensical, and that “accountability” – that is, a range of sanctions on students, teachers, and schools (but never on lawmakers, foundations, corporations, or high officials) is logical and level-headed.

A merry band of billionaires, including Fortune 500 CEOs Bill Gates, Michael Bloomberg, Sam Walton, and Eli Broad, has led a wave of “school reform” within this frame – capitalist schooling on steroids. These titans spread around massive amounts of cash to promote their agenda as “common sense”: dismantle public schools, crush the teachers’ unions, test and punish. In other words, destroy the collective voice of teachers, sort students into winners and losers, and sell off the public square to the wealthy. This peculiar brand of schooling is part of these billionaires’ social vision – that education is an individual consumer good, neither a public trust nor a social good, and certainly not a fundamental human right. It serves a society of brute competition that produces mass misery along with the iron-hard idea that such misery is the only alternative.

The education we’ve become accustomed to is a grotesque caricature, neither authentically nor primarily about full human development. Why, for example, is education thought of as only kindergarten through twelfth grade, or even kindergarten through university? Why does education occur only early in life? Why is there a point in our lives when we no longer think we need education? Why, again, is there a hierarchy of teacher over students? Why are there grades and grade levels? Why, indeed, do we think of a “productive” sector and a “service” sector in our society with education designated as a service activity? Why is education separate from production?

Schools for compliance and conformity are characterized by passivity and fatalism and infused with anti-intellectualism and irrelevance. They turn on the little technologies for control and normalization – the elaborate schemes for managing the mob, the knotted system of rules and discipline, the exhaustive machinery of schedules and clocks, and the laborious programs of sorting the crowd into winners and losers through testing and punishing, grading, assessing, and judging. All of this adds up to a familiar cave, an intricately constructed hierarchy – everyone in a designated place and a place for everyone. In the schools as they are here and now, knowing and accepting one’s pigeonhole on the towering and barren cliff becomes the only lesson one really needs.

When the aim of education and the sole measure of success is competitive, learning becomes exclusively selfish and there is no obvious social motive to pursue it. People are turned against one another as every difference becomes a potential deficit. Getting ahead is the primary goal in such places, and mutual assistance, which can be so natural in other human affairs, is severely restricted or banned.

Beyond Capitalist Education: Trudging Toward Freedom

Parents, students, citizens, teachers, and educators might press now for an education worthy of a democracy and essential to a future of free people. This would include an end to sorting People into winners and losers through standardized tests. An end to starving schools of needed resources and then blaming teachers and their unions for dismal outcomes. An end to the militarization of schools, “zero tolerance” policies, and gender-identity discrimination. An end to the savage inequalities that deprive schools in historically segregated and poor communities of the resources they need and have rarely received. All children and youth, regardless of their economic or social circumstances, deserve full access to richly resourced classrooms led by caring, thoughtful, fully qualified, and generously compensated teachers.

The development of free people is the central goal of teaching toward and within the free society of the future. Teaching toward freedom and democracy is based on a common faith in the incalculable value of every human being and the principle that the fullest development of all is the condition for the full development of each, and, conversely, that the fullest development of each is the condition for the full development of all.

At its best, socialist education would strive for this ideal. But a hundred years of history demand that we resist lazy labels or easy assertions of political purity. We know that capitalism is an exploitative system, but socialism has often presented itself in authoritarian and narrowly nationalistic shrouds, which revolutionary humanists cannot (and should not) defend. As a teacher and an activist, I want to urge a little doubt, a hint of skepticism, a word of caution, lest we trap ourselves in the prison of a single bright and blinding idea.

Just as revolutionaries living through the death throes of feudalism could not predict with any certainty the institutions that would be born in the new age, built up within the shell of the old, we cannot do more than fight for more peace, more egalitarianism, more participation, more justice, and more democracy. We would do well to bring a strong sense of agnosticism to the effort, along with our expansive dreams of freedom, our desires, our sense of play, humor, art, surprise, and, mostly, love, which is rooted in reciprocity and always renewable. Love sharpens our senses and asks us to outdo ourselves.

In a vibrant and liberated culture, schools would make a serious commitment to free inquiry, open questioning and full participation; access and equity and simple fairness; a curriculum that encourages independent thought and judgment. Instead of obedience and conformity, it would promote initiative, courage, imagination and creativity.

The schools we need – and schools that we can fight for now – are lived in the present tense. The best preparation for a meaningful future life is living a meaningful present life, and so rich experiences and powerful interactions – as opposed to a bitter pill – should be on offer at schools every day. A good school or classroom is an artist’s studio and a workshop for inventors, a place where experimentation with materials and investigations in the world happen every day. A good school is fearless, risk-taking, thoughtful, activist, intimate, and deep, a space where fundamental questions are pursued to their furthest limits.

Foundational questions that free people pursue might become the central stuff of our schools:

What’s your story?

How is it like or unlike the stories of others?

What do we owe one another?

What does it mean to be human in the twenty-first century?

What qualities and dispositions and knowledge are of most value to humanity?

How can we nourish, develop, and organize full access to those valuable qualities?

Why are we here?

What do we want?

What kind of world could we reasonably hope to create?

How might we begin?

These questions – themes in literature and the arts through the ages – are not as lofty and distant as they might sound. In a preschool, a teacher might organize a “Me Curriculum” and interview each child, reserving a section of wall devoted to a “kid of the week” that spotlights each one, with kids telling the story of their family, how they got their first name, their favorite books and food, and more. In third grade, students might interview a “family hero” and present oral histories to the group, focused on significant events in their life, migration or movement, and life lessons learned. A group of middle-school students might spend a year exploring the environment of their neighborhood, mapping everything from housing and labor patterns to health and recreation and crime statistics.

High school kids might develop a rich and varied portfolio for graduation, a set of works to be defended in front of a committee consisting of an advisor, a peer, a teacher, a community resident, and a family member. This might consist of grades and test scores (in the short-term, as the system transitions), along with an original work of art, a physical challenge set and met, a favorite piece of writing, a record of community service, a work/ study plan for the next four years, a list of the ten best books they’ve read, an essay on “What Makes an Educated Person,” and a list of the books and essays they want to read, films they want to watch, and projects they plan to pursue in the next five years. And so on.

We learn skills, facts, and knowledge in a context. In a future free society, that context would be the pursuit of a free and productive life for all.

Our schools would resist the overspecialization of human activity, the separation of the intellectual from the manual, the head from the hand, the heart from the brain, the creative from the functional. The standard would become fluidity of function, the variation of work and capacity, the mobilization of intelligence and creativity and initiative and work in all directions.

Where active work is the order of the day, helping others is not a form of charity, something that impoverishes both the recipient and the benefactor. Rather, a spirit of open communication, interchange, and analysis becomes commonplace. In these places, there is a certain natural disorder, a certain amount of anarchy and chaos, as there is in any busy workshop. But there is a deeper discipline at work: the discipline of getting things done and learning through life.

On the side of a liberating and humanizing education lies a pedagogy of questioning, an approach that opens rather than closes the process of thinking, comparing, reasoning, perspective-taking, and dialogue. It demands something upending and revolutionary from students and teachers alike. Repudiate your place in the pecking order, it urges, remove that distorted, congenial mask of compliance: You must change!

We would learn to embrace the importance of dialogue with one another. In dialogue, one speaks with the possibility of being heard and simultaneously listens with the possibility of being changed. Dialogue is both the most hopeful and the most dangerous pedagogical practice, for in it, our own dogma and certainty and orthodoxy must be held in abeyance, must be subject to scrutiny.

The ethical core of teaching toward tomorrow must be designed to create hope and a sense of agency and possibility in students. There are three big lessons. History is still in the making, the future is unknowable, and what you do or don’t do will make a difference (and, of course, choosing not to choose is itself a choice). Each of us is a work in progress – unfinished, dynamic, in-process, on the move and, yes, on the make – swimming through the wreckage toward a distant and indistinct shore. And, finally, you don’t need anyone’s permission to ask questions about the world.

Teachers with freedom on their minds would come to recognize that the opposite of moral is indifferent, and that the opposite of aesthetic is anesthetic. They would encourage students to become engaged participants in life, and not passive observers. They would encourage students to see the splendor and the horror, to be astonished at both the loveliness of life and all the undeserved harm and pain around us, and then to release their social imaginations in order to act on what that knowledge demands.

The challenging intellectual and ethical work of teaching pivots on our ability to see the world as it is and to see our students as three-dimensional creatures – human beings like ourselves – with hopes and dreams, aspirations, skills, and capacities; with minds and hearts and spirits; with embodied experiences, histories, and stories to tell of a past and a possible future; with families, neighborhoods, cultural surroundings, and language communities all interacting, dynamic, and entangled. This requires patience, curiosity, wonder, awe, and more than a small dose of humility. It demands sustained focus, intelligent judgment, inquiry, and investigation. It calls forth an open heart and an inquiring mind, since every judgment is contingent, every view partial, and each conclusion tentative.

In any liberating pedagogy, students become the subjects and the actors in constructing their own educations, not simply the objects of a regime of discipline and punishment. Instead of credentialing, sorting, gate-keeping, and controlling, education should enable all students to become smarter, more capable of negotiating our shared and complex world, better able to work effectively in and across communities to innovate and initiate with courage and creativity. This requires courage and determination – from teachers, families, communities, and students – to build alternative and insurgent classrooms and schools and community spaces focused on what we know we need rather than what we are told we must endure. We must transform education from rote boredom and endlessly alienating routines into something that is eye-popping and mind-blowing – always opening doors and opening minds and opening hearts as students forge their own pathways into an expansive world.

Knowledge is an inherently public good, something that can be reproduced at little or no cost. Like love, it’s generative: the more you have, the better off you become; the more you give away, the more you have. Offering knowledge and learning and education to others diminishes nothing. In a flourishing democracy, knowledge would be shared without any reservation or restrictions whatsoever. This points us toward an education that could be about full human development, enlightenment, and freedom.

Copyright 2014 by Frances Goldin, Debby Smith and Michael Steven Smith. Not to be reprinted without permission of the editors or HarperCollins.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $47,000 in the next 8 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.