Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Dr. Elaine Enarson is a disaster sociologist, an international consultant on gender-responsive disaster reduction, and the author, most recently, of Women Confronting Natural Disaster: From Vulnerability to Resilience. The editor of The Women of Katrina: How Gender, Race, and Class Matter in an American Disaster, Enarson is a founding member of the Gender and Disaster Network and lead developer of a new course on social vulnerability at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

I first met Elaine when I was 20 and dating one of her sons. I remember visiting his family in Colorado in August of 2005, during Hurricane Katrina, and being as glued to Elaine’s illuminating analysis as to the heartbreaking images on the television.

As we lurch today from one intensified – or unprecedented – natural disaster to another, more people have and will have direct experience with these events. The popular images of communities coming together, of people at their best, often conceal a much darker reality of amplified inequalities and increased danger for at-risk populations.

Disasters disproportionately affect women, people of color, and the poor – posing both immediate dangers and long-term challenges. Pre-existing problems like gender-based violence, custody conflicts and insecure work or housing are exacerbated, while the resources and organizations that usually offer support become undermined in times of crisis. Temporary solutions, such as shelters and relief camps, often prove to be both unsafe and long-lasting.

Elaine’s work re-imagines risk prevention beyond prepping: the meaningful steps that communities, organizations and governments should take long before the first sirens go off. We had a conversation recently about her formative experiences, climate change, the variables of disasters, how to organize for resilience, and ways humans make a natural event into a disaster.

Hurricane Andrew: The Origins of a Disaster Specialist

Josephine Ferorelli: The focus of your scholarship shifted from gender in the workforce and domestic violence to gender in disasters in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew. Can you say a little bit about the galvanizing aspects of that experience?

Elaine Enarson: We bring our histories to disasters along with our bodies, relationships, and ‘stuff’.’ Part of my recent history had been working with the domestic violence movement in Nevada and, before that, examining how occupations segregate and re-segregate to maintain privilege. So when I finally got my senses back after Andrew came to my neighborhood (this took awhile!) one of the first places I wanted to visit was the local battered women’s shelter.

With some terrific colleagues at Florida International University, we sought out low-income migrant women, women doing home-based childcare, women in public housing and others whose economic security was at issue. Looking back, I think I learned the most from the African American women in public housing who came together like the family they truly were. I also had a wonderful lesson in post-disaster grassroots organizing through participatory research with the Women Will Build Miami coalition, now part of a book called The Gendered Terrain of Disaster: Through Women’s Eyes.

JF: Have other disasters become pivot points or moments of clarity for your work?

EE: Making my way from Colorado to the northern Indian state of Gujarat after a massive quake there in 2001 was another galvanizing moment. Again, I was able to see women at the grassroots stepping up through the Self-Employed Women’s Association, a union for women in the informal sector. I participated in a local research project designed around mitigation, not vulnerability or response, sponsored by the Disaster Mitigation Institute in Gujarat. This also taught me what community-based and gender-sensitive action research looks like and can accomplish, both at the village level and in policy and planning realms.

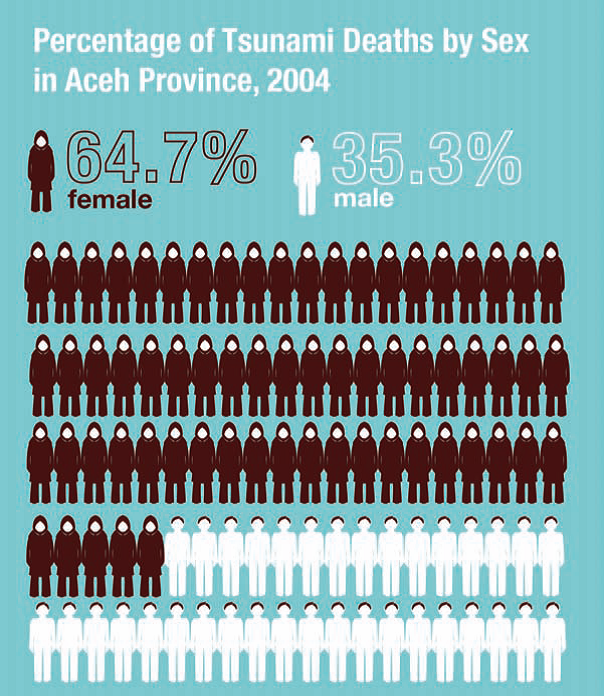

I felt the same way later interviewing women in Banda Aceh who were rebuilding traditional women’s spaces destroyed by the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, not only designing and operating, but also physically reconstructing them. In all my disaster research, the incredible determination, spirit, and skill of girls and women never ceases to amaze me. From hurricane Andrew in Miami to the massive floods of the Red River in the Upper Midwest, I’ve been privileged to listen as women shared what they did in disasters and how they felt. We have only to look to appreciate what women do, as I titled one article, so why don’t we? Why are sex, sexuality, and gender relations so marginalized in disaster studies? Why are men’s lives in disasters not yet examined from a critical gender perspective by other disaster researchers? It’s still a puzzle to me.

Climate Change: New Normals and Stronger Alliances

JF: Your first book was Woods-Working Women: Sexual Integration in the U.S. Forest Service (1984). Has the new normal of annual forest fires in your home state of Colorado brought forestry back into your thinking?

EE: Living in the wildland interface, with lovely green pine trees all around, certainly raises anyone’s awareness of fire hazards and the need to reduce these, both by mitigation and by preventing development in fire-prone areas to begin with. Recently I’ve been involved in some wonderful work with colleagues in Australia studying violence against women in the bushfires of Black Saturday, and then, in a real first for the field, through the eyes of men, reflecting on how constructs of masculinity endanger both men and boys and their intimates. I follow the movement of women into forestry and fire fighting with interest, noting both the persistence of resistance to ‘feminization’ of forestry and of fire-fighting (in many ways is just as fierce as when I studied it long ago) and the growth of a critical mass of women who are changing things. It’s a wonderful thing to see.

JF: How has focus on climate change evolved in the field of disaster studies?

EE: It’s a short hop from thinking about sex, sexuality, and gender relations in crisis, including in the face of disasters, to thinking about climate change with a gender lens. Further, the gender and climate community of practice has been a welcome force internationally, hard to miss without willfully looking away.

There are few climate change deniers in our field, naturally enough. Though the field of emergency management leans to the right, climate facts on the ground are persuasive to academics, practitioners, and policy makers, as they surely are to residents whose lives are turned upside down by increasingly severe and uncertain weather events.

But integrating climate change mitigation and adaptation into community work around sustainability, vulnerability reduction, and hazard mitigation—-is very hard. One discouraging thing I’ve observed is the climate community ‘recreating the wheel’ by not connecting closely to decades of analysis and social action in the larger hazards and disaster community of practice. Worse, I see the same replication in gender analysis, with gaps too large between the efforts of gender, climate, and disaster activists and others. I wrote an article about this recently for a book called Research, Action and Policy: Addressing the Gendered Impacts of Climate Change, and hope to work more in future with others to find or make more common ground.

We simply do not have time to play exclusively in our own fields of interest any longer. Disaster reduction movements in the nations most affected by global warming (already and in the future) are on the forefront of change, helping others to see these connections on the ground and address them politically. Anyone following the climate negotiations probably shares my pessimism about how likely it is that the U.S. will step up responsibly, but resistance will not be lead by careful students of disaster. Young feminists and other activists in the U.S. may come to climate work with the same passion that my generation brought to reproductive rights and other struggles.

Certainly, at a global level, grassroots women are taking the lead, and the U.S. did host a recent climate justice/gender justice conference with representatives from around the world. But do climate activists in the U.S. understand how essential women’s leadership is? How much we can learn from women’s hard-won disaster experience? How gender and other oppressive constructs must be confronted directly as we strategize about a climate justice movement and plan ahead to support those on whom the greatest burdens will fall?

The Variables of Disaster

JF: In what ways do disasters play out similarly/differently in Western and non-Western countries? In what ways are each better and worse equipped to confront disasters?

EE: All the obvious differences about development come into play, because disasters are fundamentally social, not ‘natural’ or environmental events. They arise from and make abundantly clear the fracture lines of any society and any region. There is no substitute for a functioning early warning system that alerts people to a quake and possible tsunami, and this is far more likely, still today, to be available in wealthy countries. The economic resources are simply not there to implement what we know can reduce human suffering, especially in the parts of the world that are most at risk. The institutional capacity and political will are also often lacking, though not exclusively in poor nations by any means.

The livelihoods of the poor and those on the margins are often extremely vulnerable to the social and environmental effects of disasters. But we must not overlook the value of indigenous knowledge and experience, the highly effective risk-communication systems built on social networks and face-to-face (often woman-to-woman) communication that we see in poor countries, along with families and traditions that hold fast through crises, time and time again. Disasters are not new to most of us on earth, and certainly not new to the poorest of the poor in every country. Without romanticizing the resilience of the poor, there are essential lessons learned and shared that all of us can benefit from. Every disaster is unique, but common patterns play out, too. Because the U.S. experience is unique, a small but hardy band here at home started the U.S. Gender and Disaster Resilience Alliance, whose resources can still be accessed though it is currently on hiatus.

JF: Are some disasters more gendered than others (do certain kinds of disasters exacerbate inequalities and gender-based violence more than others)?

EE: Great question and one we should strive to answer. Disasters resulting in significant housing loss (and not all do) are more difficult for women, given the prevailing housing insecurity of women globally and the dynamics of disaster capitalism that are so apparent so quickly. This increases vulnerability to domestic violence ‘behind closed doors’ when those doors may be the home of your abuser, to which you had to return when other housing options were lost. Disasters involving release of toxics clearly imperil women’s reproductive health (and men’s, no doubt, though this is rarely examined). Because women are caretakers with enormous and expanding responsibilities in crises, pandemic flus have had and will have especially grave consequences for women. The website of the global Gender and Disaster Network is a great resource for more on this subject.

Organizing for Resilience

JF: You say that organizations that provide social resources, like domestic violence prevention services, face sudden obstacles during and after disasters. For example: a loss of volunteers/staff, damaged workplace/equipment/supplies etc., disrupted communications with collaborators and supporters, funding disruptions. They will be asked to do much more with less, and may need to be completely repurposed for different kinds of care and support. How does an organization or activist group put together an emergency preparedness plan?

EE: Women’s and community groups have essential roles to play in disasters—before, during and after. We focus mainly on the ‘after,’ when the support and resources they offer are a lifeline to those they serve. But we must focus on the time ‘before’: more accurately, the ‘between’ time, as successive disasters is the new normal. Thinking about preparedness and mitigation is too often cast as a personal responsibility. We do all want to be as prepared as is feasible, but it is the collective work we do in advance to protect the public good and promote people’s fundamental human rights in disasters that helps build resilience and saves lives.

Unfortunately, in this era of retrenchment, defunding, privatization, and increasing inequalities, women and women’s organizations are truly the ‘shock absorber’ of disasters; we rely on them as long-term responders, still with us long after the big men, big trucks, and big money have left town. So I call on women’s and community groups to do their homework, learn from historical experience what is likely to constrain their disaster work, determine what level of support they want to continue to provide if humanly possible, and then build capacity to meet their own expectations. This means searching out good models for disaster planning and [USGDRA( https://usgdra.org/), and doing the fundraising necessary to undertake the most relevant preparedness and mitigation steps recommended. It means putting disaster resilience at the center of our work, not pushing it aside for another day. If we are always ‘too busy’ or ‘too broke’ to think ahead, we will continue to pay a very dear price.

JF: And what are the philosophical, less nuts-and-bolts kinds of preparations that groups and individuals can make to increase our resilience?

EE: Politically, disaster risk reduction demands a rethink about our social, economic, and political institutions, and about the values that we want to guide human action and interaction on our volatile planet. Disasters are ‘designed’ though choice; as such, they are socially produced events and can be prevented or reduced in their effects. But this means moving ‘disaster’ back to the future—away from the purview of technical “experts” or military-based “responders” or political “crisis management,” and toward the kind of embedded awareness of hazard reduction and solidarity that protected the first Americans and their settlements.

Disasters are complex human problems arising from short-sighted, self-interested decisions taken over many, many years that increase our exposure to known hazards and that have increased, rather than reduced, social vulnerabilities tied to race/ethnicity, class, gender/sexuality, age, ability, and all the other power dynamics of our era. Those most at risk – those least able to anticipate, prepare for, cope with, survive, and recover from disasters – are those most marginalized politically and economically. But paradoxically, decades of disaster research shows that those in the ‘eye of the storm’ also bring local knowledge, social connections, core values supporting collective action, and specific life-preserving skills arising from hard times.

In the long run, those most vulnerable to hazards and disasters are at the center of disaster risk reduction in every society, the U.S. included. It’s an article of faith for me that people can and will work for the larger good when the necessary knowledge and resources are at hand. Concretely, this means that in every way that people organize today (and this is a rapidly changing field as we know) hazard awareness is on the radar screen, and people strive to make the connection between social justice and human rights in our everyday life and disaster vulnerability. It’s a big ask but a critical one.

JF: As we enter an era of more frequent, intense, and unpredictable natural disasters, what models of preparedness and relief should we look to as states, cities, groups, and individuals?

EE: The low-hanging fruit is preparedness, which rapidly descends to individual emergency plans and stockpiling. This further limits the already scarce social space for thinking about reducing the impacts of disaster and preventing them altogether. “Disasters” are the logical culmination of development decisions, not reducible to the triggering hazards we create or live with necessarily. It is always tempting to look for short-term, illusory fixes and to look way from the root causes that put us at risk in the first place. The focus of preparedness is on limiting impact, and hence limiting emergency response and relief efforts.

We must enable people to protect themselves to the best of their ability (and support them in this), working through neighborhood associations and NGOs, along with state and private sector actors. But how badly we need to shift gears to prevention! Every private and public decision taken that affects disaster risk (and few do not) must be examined from a disaster prevention perspective, with an eye on the long game, because disaster risk reduction is about our future and the world we want to create. It is about social justice and the right to protection against avoidable, predictable harm and suffering.

Reducing the risk of disaster should be a primary organizing principle of development and planning in the public sector, and of course in the private sector, where far-reaching decisions are so often made without meaningful public engagement. Even in progressive spaces, the need to consider natural hazards isn’t always obvious; for example building out cooperative and green housing on a low-cost flood plain, or housing a people’s health clinic or child-care center in a structure not ‘hardened’ against a known quake fault. Clearly, people in future will be less able to look to the state for meaningful support, for better or for worse, and correspondingly more co-dependent, especially at the neighborhood level. This challenges our community-based sustainability movements and diverse social justice movements to step back and consider how best to integrate disaster risk reduction into the work already underway.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Our fundraising campaign is over, but we fell a bit short and still need your help. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.