Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

There is lots of talk now about Apple’s cash hoard, which is actually kind of amazing: this is supposedly our cutting-edge technology company, and apparently it can’t find things it wants to invest in. Or more accurately, given its incredible profits, it can’t find enough things to do with all the money it makes.

So, I’ve had a mild-mannered dispute with the economist Joe Stiglitz over whether individual income inequality is retarding recovery right now; let me say, however, that I think there’s a very good case that the redistribution of income away from labor to corporate profits is very likely a big factor.

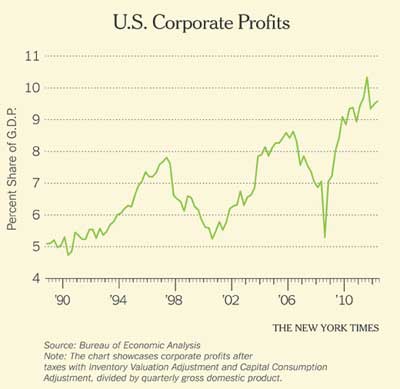

Take a look at the chart on corporate profits as a share of gross domestic product. Corporations are taking a much bigger slice of total income — and are showing little inclination either to redistribute that slice back to investors or to invest it in new equipment, software, etc. Instead, they’re accumulating piles of cash.

Still Say’s Law After All These Years

Still Say’s Law After All These Years

When the economist John Maynard Keynes wrote “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” three generations ago, he structured his argument as a refutation of what he called “classical economics,” and in particular of Say’s Law, the proposition that income must be spent at some point and hence that there can never be an overall deficiency of demand. Ever since, historians of thought have argued about whether this was a fair characterization of what the classical economists, or at any rate Keynes’ own intellectual opponents, really believed.

Not being a historian myself, I won’t venture an opinion on that subject. What I will say, however, is that Say’s Law (Say’s False Law? Say’s Fallacy?) is something that opponents of Keynesian economics consistently invoke to this day, falling into exactly the same fallacies that Keynes identified back in 1936.

In the past I’ve caught economists like Brian Riedl and John Cochrane doing this; Peter Dorman, writing in a recent blog post, found Tyler Cowen in their company. Mr. Cowen can’t see why corporate hoarding is a problem. Like Mr. Riedl and Mr. Cochrane, he concedes that there might be some problem if corporations literally piled up stacks of green paper, but he argues that it’s completely different if they put the money in a bank, which will lend it out, or use it to buy securities, which can be used to finance someone else’s spending.

But of course there isn’t any difference. If you put money in a bank, the bank might just accumulate excess reserves. If you buy securities from someone else, the seller might put the cash under his mattress, or put it in a bank that just adds it to its reserves, etc. The point is that buying goods and services is one thing, adding directly to aggregate demand; buying assets isn’t at all the same thing, especially when we’re at the zero lower bound.

What’s depressing about all this is that Say’s Law is a primitive fallacy — so primitive that Keynes has been accused of attacking a straw man. Yet this primitive fallacy, decisively refuted three-quarters of a century ago, continues to play a central role in distorting economic discussion and crippling our policy response to depression.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have only 72 hours left to raise $25,000. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.