Truthout is a vital news source and a living history of political struggle. If you think our work is valuable, support us with a donation of any size.

One hundred and twenty-two years ago, Ida B. Wells, an African American journalist who reported on the horrors carried out by white lynch mobs against Southern blacks, penned a oft-pronounced slogan that still rings true today: “This is a white man’s country and the white man must rule.”

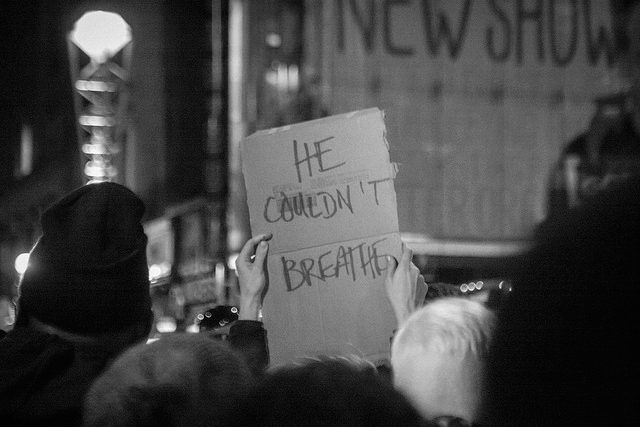

This year, the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner further cement these words. In the past three weeks, grand juries decided not to indict the police officers who caused the deaths—Darren Wilson and Daniel Pantaleo—for any crime.

Following the announcement of Wilson’s non-indictment, the grand jury released his sworn statement. His words reveal a narrative so grossly entrenched in our American culture that it goes uncontested to this day: this is the narrative of white innocence.

“White innocence is the insistence on the innocence or absence of responsibility of the contemporary white person,” argues Thomas Ross, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh Law School. What this means is that white people will not be considered guilty of a crime simply because on the color of their skin. This is due to the fact that white innocence is historically predicated on the criminalization and violation of (primarily) black bodies. The framing of whites throughout United States as inherently innocent and blacks as guilty not only encourages the continued perpetuation of white violence against black people, such as physical police violence, the discriminatory enforcement of laws, and mass incarceration, but also makes it a necessary condition of the state, as the state maintains its power and dominance through the criminalization of (mainly) black people.

Wilson’s testimony reveals how the historically rooted rhetoric of white innocence not only goes unchallenged but is also state-sanctioned. In his testimony, Wilson frames himself as fearing for his life despite the fact that he was carrying multiple weapons on his body the day he chose to murder Brown, such as his baton, flashlight, mace, and gun. He expresses feeling threatened by Brown’s use of “vulgar language,” and that Brown’s motion to move toward him was done to “intimidate” and “overpower” him. Wilson alleges that there was an altercation between him and Brown, where Brown approached his police vehicle and threw punches, making Wilson feel trapped inside his vehicle. Wilson claims that when he grabbed Brown’s arm to stop him, he “felt like a five year old holding on to Hulk Hogan,” and that “that’s just how big he [Brown] felt and how small I [Wilson] felt grabbing his arm.” That Wilson describes himself as feeling significantly smaller is not alarming. Anne McClintock writes in Imperial Leather that historically white masculinities have been constructed through the violence committed especially against black people. Wilson makes clear that he was made to feel emasculated with Brown’s use of “vulgar language,” and his alleged threatening behavior. Let’s recall that the use of vulgar language or whistling by black men, especially in the presence of white women, has been sufficient to get them killed, as was the case with Emmett Till.

Wilson then fired through the glass window of his police car, and Brown backed away. As Wilson described it, Brown “had the most aggressive face. That’s the only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.”

Wilson’s use of the word “demon” to describe Brown reinforces how the theme of white innocence dates back to settler-colonialism. Using Christianity as a weapon, Christian settlers ventured out on civilizing missions because they perceived native peoples’ as heathens, and required them to convert to Christianity as a form of salvation. When indigenous people refused, they were considered infidels. In the book American Holocaust, David Stannard explains, “Such infidels thus became, in the popular Christian image, ‘demons in human form.'” That Wilson uses this language to describe Brown is not alarming when we consider the historical context out of which it emerges.

Sylvester Johnson, an African American and Religious studies scholar at Northwestern University, explains:

“White innocence is a narrative that is usually uncontested because it is foundational to basic US structures, and the US could not exist as a White racial state without the forced displacement and genocide against Indigenous peoples. The US economy emerged through racial slavery. These are fundamental conditions that enable the possibility of White dominance. To critique the role of racism and colonialism is to question the very legitimacy of the United States.”

Wells wrote “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all Its Phases” (one of three treatises sold through the New York Age Print for 15 cents a piece) in 1892, in order to document how laws legalizing lynching were established as a way to halt the racial and economic progress of Southern blacks. Wells’ anti-lynch campaign successfully exposed how the Jim Crow systems that white Americans put into place after slavery ensured that white violent mobs and complicit police officers could terrorize black people without any legal consequences.

What’s important to note here is that Wells’ reporting made the narrative of white innocence clear to the public. She documented that while the overwhelming majority of documented crimes were committed by the whites—such as the raping of black girls and women, beatings, burnings, castrations, and public lynchings— blacks were already assumed to be guilty. She showed that a third of the nearly 1,000 black people who were lynched by mobs in the United States during the 1890s were not even charged with any crime—the rest, of course, did not get any chance for a trial.

This is the way white innocence is supposed to work: black people, and people of color more generally, are always guilty even when they are not charged with a crime. And when black people are charged with a crime they are oftentimes wrongfully accused. This holds true all the way from the angry mobs of the 1890s, to the endless imprisonment without crime of Muslim men in Guantanamo, to the lack of prosecution for the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown. This is a white man’s country and the white man’s rule of law must rule. Trudier Harris tells us in her book Exorcising Blackness: Historical and Literary Lynching and Burning Rituals that lynching was “the final part of an emasculation that was carried out every day in word and deed. Black men were things, not men, and if they dared to claim any privileges of manhood, whether sexual, economic, or political, they risked execution.”

In his testimony, Wilson absolved himself of murder by appealing to the dominant ideology that black is criminal and poses an ongoing threat to whiteness and white innocence in his attestation. With a majority of white people’s investment in white innocence, Wilson is able to get off free without facing any consequence to continue reinforcing the narrative of white innocence.

As New York City mayor Bill de Blasio noted while thousands of people protesting the lack of an indictment in Eric Garner’s case filled the streets of Manhattan last night, we have to reflect on the “centuries of racism that have brought us to this day.” The fact that “Black Lives Matter” is a phrase that bears repeating even today is upsetting. “It’s a phrase that should never have to be said,” the mayor said. “It should be self-evident.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have a goal to add 182 new monthly donors in the next 24 hours. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.