On its website, TransCanada touts a near-spotless spill record from 2002 to 2011 for its oil pipelines.

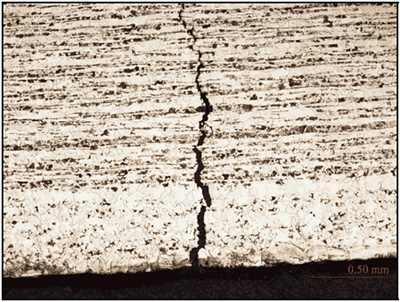

However, the company wasn’t always perfect. One of its natural gas pipes ruptured 18 years ago near Rapid City, Manitoba. While that rupture and an ensuing blaze did not garner much media attention at the time, the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, which examined the pipeline, reported that “external stress corrosion cracking” caused the break.

TransCanada now wants to convert the same pipeline to carry 1.1 million barrels a day of viscous, highly corrosive tar-sands crude at high pressure as part of its Energy East Pipeline across six Canadian provinces, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, which has been tracking the oil company’s proposal, and TransCanada documents detailing the project.

Farther south in New England, ExxonMobil and Enbridge Inc. have plans to pipe tar sands crude through a pipeline originally constructed in 1950 to transport conventional oil.

These projects are just two examples of pipeline conversions driven by what independent energy experts describe as a big push to get millions of barrels of Canadian tar sands oil to refineries on the coast that can process the heavy crude.

Across Canada and the United States, from the Midwest to New England, oil companies are trying to push tar sands dilbit – the heavy, almost-solid bitumen thinned with a concoction of liquid natural gas and other hydrocarbons – through aging pipes because under current federal regulations, conversions can be done “without making a lot of noise,” said Richard Kuprewicz, president of Washington-based pipeline safety firm Accufacts Inc.

Conversely, new pipelines such as TransCanada’s Keystone XL Pipeline trigger several levels of federal scrutiny, including a lengthy environmental review.

Although using existing pipes avoids lengthy permitting process and public scrutiny and is less costly, independent experts say the older pipes bring other challenges. The heavier, high-sulfur dilbit from Canada could both create bigger pressure swings and cause microscopic cracks to spread in old pipes.

“In general it’s more difficult for an older pipe to transport tar-sands dilbit,” Kuprewicz said.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) is calling on the Obama administration to look at the trend of pipe conversions to dilbit, said Danielle Droitsch, director of the Canada Project at the NRDC. There is no policy on pipeline safety or, equally important, spill response.

“Spills in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and Mayflower, Arkansas, demonstrate that tar sands crude is more damaging and difficult to clean up, particularly if it contaminates water bodies,” said Anthony Swift, an attorney with NRDC, in his testimony before a House subcommittee in Washington on Sept. 19, 2013.

While not the largest pipeline spill in US history, the Enbridge Kalamazoo tar-sands spill has become the most expensive involving a pipeline – with cleanup costs rising above $1 billion. “The extent of damage done to the region’s watershed may not be known for years to come,” Swift said in his testimony.

In Mayflower, days after the Pegasus pipe rupture, air-monitoring tests showed dangerous levels of benzene and other toxic chemicals. Six months after the spill, some still complained of health problems like headaches, nausea and vomiting that have plagued families near the cove where much of the tar sands sediment remains buried.

A handful of existing pipelines, such as the Pegasus line, already have been converted. Many more projects to convert older pipes are springing up, from the Canadian pipe that ruptured in 1995 to an aging pipeline stretching from Illinois to the Louisiana coast. Enbridge is working with another company to change that pipe from natural gas to dilbit.

As projects such as the Keystone XL are held up in lengthy review processes, Mohammad Najafi, director of Construction Engineering & Management at the University of Texas at Arlington, has seen oil companies relying more on existing pipes for tar sands transport – rather than embark on new pipeways. “It’s an easier process,” Najafi said about converting the old pipes.

“A chess game”

In most cases converting pipes already underground triggers minimal permitting. The federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, which oversees the regulation of interstate pipelines, and the State Department, which oversees pipes coming across Canada, do not require an environmental review or thorough permitting process, for conversions. Kuprewicz tells Truthout.org:

“The process of converting either existing gas or conventional oil lines to tar sands does not trigger any kind of lengthy review. Some companies have figured that out. That’s why they are trying to convert these older lines.”

“It’s kind of a chess game going on,” said Kuprewicz, whose consulting firm provides pipeline expertise to government agencies, the industry and other parties.

In some cases, lines are being converted with little research into the impact of the switch to dilbit. “Some of these companies are becoming masters of loopholes, instead of just stepping back and doing the right thing,” Kuprewicz said.

If oil companies carry through on their proposals, a network of old gas and oil pipes converted to move tar-sands dilbit will dot maps through the United States. Many of the pipes were built in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

“I think it’s more widespread than people think,” Kuprewicz said. “How many will come online and when? That’s anyone’s guess. There is a difference between proposals and companies actually doing them.”

Canada is producing more and more tar sands bitumen, but most of the fossil fuel remains landlocked in Canada. “At the end of this decade, there will be 5 million barrels a day of Canadian oil production,” said Tom Kloza, an oil analyst with Oil Price Information Service. “That’s mostly Alberta tar sands.”

Oil companies are paying engineers a lot of money to figure out how to get the Canadian extracted dilbit to the coasts, where it can be refined and shipped to international markets, and the big option right now is piping it through pipes already under the ground.

“They want to get that oil out of Canada,” said Kuprewicz, who compared the effort to a modern Gold Rush.

Under stress

If completed, TransCanada’s Energy East project would pump dilbit from Alberta to refineries in Eastern Canada. The dilbit would travel along 870 miles of new pipeline that connects to 1,864 miles of the older pipe.

The existing 42-inch-wide pipe was built in the 1970s, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, which has been tracking the oil company’s proposal. A media representative for TransCanada directed Truthout.org to the project’s website but did not return calls for comment for this article.

Heat released from the ruptured 42-inch pipe in Manitoba triggered a blaze in a nearby pipe, burning an estimated 692,163,000 cubic feet of natural gas. A TransCanada employee suffered minor cuts and bruises, and a compressor station was destroyed, along with four control buildings damaged.

The rupture illustrates two main potential problems with the current Energy East project and the trend of converting older lines to transport dilbit.

“Whoever is going to convert that (Energy East) line is going to have to look at that threat,” Kuprewicz said. “They should be looking at it.”

First, tar sands oil would force the older pipe to withstand extremes in pressure because the viscosity of dilbit can fluctuate, thus changing the pressure through the pipelines.

“The industry is trying to deny it, but they have had too many ruptures when the pressure cycling associated with dilbit operation has contributed to rupture failure,” Kuprewicz said.

Another potential problem with the TransCanada proposal is that tar sands dilbit contains hydrogen sulfide, an element that has been shown to worsen external corrosion and cracks such as the ones found in the 42-inch pipe.

After reviewing the Transportation Safety Board of Canada report on the 1995 rupture, Patrick Pizzo, a retired professor in materials engineering at San Jose State University who has studied how pipelines fail, said dilbit could prove to cause further ruptures in the pipe.

The element of hydrogen sulfide is bad news in a pipe that has shown this kind of corrosion, Pizzo said.

“When you have stress corrosion cracking in steel, the environmental ingredient that causes it to grow is hydrogen. Hydrogen can be absorbed into steel. All that hydrogen will travel to the tip of that flaw. In doing so, it weakens the bond between ion atoms, and the crack expands.

Pizzo noted that investigations showed the Mayflower, Arkansas, rupture of the Pegasus pipe followed the conversion of the pipe to dilbit. That Arkansas break in 2013 caused hundreds of thousands of gallons of tar-sands oil to spill. The pipe built in the 1940s was converted by ExxonMobil to pipe dilbit south.

Many questions

Kuprewicz said that from an engineering standpoint it is possible to pipe dilbit through older steel pipes, but there are many questions that should be answered before an existing pipe is converted to transport diluted bitumen. “What’s the type of pipe?” asked Kuprewicz. “What’s the condition of this pipe? When was it last tested?” For projects such as ExxonMobil and Enbridge’s conversion through New England, those questions haven’t been answered – at least not publicly, he said.

Besides pressure swings and the potential to worsen microscopic cracks, there are other concerns.

Dilbit can be harsher on pipes than conventional oil or natural gas, and it requires more pumping stations. Even when it’s diluted with hydrocarbons, it can still be up to 70 times more viscous than conventional oil, generating higher friction and temperatures in a pipe. It contains more abrasive sand particles and up to 20 times more corrosive acid concentrations.

Kuprewicz finds fault with a National Academy of Science conclusion in June that found tar-sands dilbit to be similar to heavy crude. “Someone didn’t do their homework or isn’t answering all the questions,” Kuprewicz said.

While no technology is risk-free, there is less risk with newer pipes built to modern standards, Najafi said.

The biggest risk is the toll a spill has on the watersheds and people. The Kalamazoo spill was so bad that contaminated oil remains trapped in river sediment, and the oil is stirred up by motorboats. According to Swift, with NRDC, the spill cleanup continues. But now EPA officials have focused on ensuring new areas are not contaminated, concluding that it would be too damaging to fully clean the nearly 40 miles of the Kalamazoo River that already are contaminated by tar sands.

A call for closer review

“There is a growing mountain of evidence that because tar sands (oil) is a very different substance than crude, it creates higher temperatures and higher pressures inside the pipe,” Droitsch said.

Droitsch said the entire system of regulation for both new tar-sands pipeways and conversions needs to be re-evaluated at the federal level, especially in the wake of the Pegasus line that ruptured.

Environmental groups such as the Sierra Club have described tar sands crude as the most toxic fossil fuel on the planet because it leaves scarred landscapes and a web of pipelines and polluting refineries in its wake, while delaying North America’s transition to a clean-energy economy.

They also worry that using older pipes could lead to a spill like the one that happened in Mayflower.

“We have only just stated to look at diluted bitumen going through pipes, and we are starting to see some statistics that there is a larger volume of tar sands spilling than with conventional crude,” Droitsch said. “The government should be looking into this – especially after the Arkansas spill.”

That kind of closer look hasn’t been happening, Droitsch said.

It leaves oil companies largely responsible for pipeline safety.

Kuprewicz, the pipeline expert, said that while some companies are taking pipeline safety seriously, others are trying to increase revenue streams while cutting corners.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.